Art: His insights became cliches

Edward Weston (1886-1958) created some of the most memorable cliches in modern photography - not intentionally, but, ironically, because he possessed an exceptional eye for the elemental beauties and symmetries in nature.

Edward Weston (1886-1958) created some of the most memorable cliches in modern photography - not intentionally, but, ironically, because he possessed an exceptional eye for the elemental beauties and symmetries in nature.

Weston's distillations of nature's architecture are so insightful and elegant that they have not been surpassed, and, in fact, could not be.

No other photographer has penetrated so deeply into the essence of form, or been so inventive in his formal explorations.

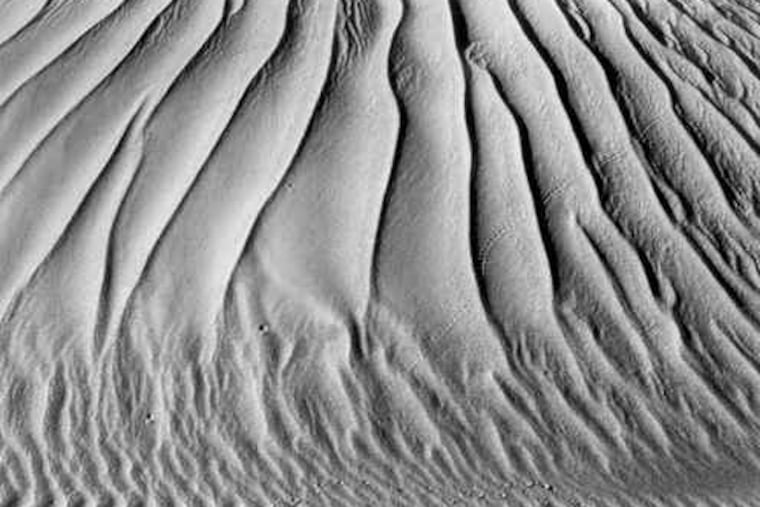

It was inevitable, then, that legions of photographers, amateur and professional, who followed in his footsteps would produce countless images of seashells, vegetables, ripples in sand, tidal wash, and the nude human body.

While some of Weston's visual concepts have become cliches, his own realizations of those concepts remain as fresh and striking as when they were made. This paradox is abundantly evident in an exhibition of Weston's photographs, the majority vintage prints, at the James A. Michener Art Museum in Doylestown.

"Edward Weston: Life Work" is a condensed retrospective of more than 100 prints organized thematically to cover all the artist's major themes, from portraits and landscapes to the memorable still lifes and nudes for which he became renowned.

Every photograph in the show, organized by Art2art Circulating Exhibitions, comes from a single private collection formed by Judith G. Hochberg and Michael P. Mattis, who live in Westchester County, N.Y. They acquired most of their prints from members of Weston's family (he had four sons), including a large collection from Dody Weston Thompson, a daughter-in-law.

Versions of the Michener show have been traveling around the country throughout this decade; one appeared at the Allentown Art Museum in 2003. In addition, Hochberg and Mattis' photos have been reproduced in a lush 252-page book published by Lodima Press of Revere, Bucks County.

Impressive though it is, this exhibition doesn't break new ground. Weston has become such an iconic figure in modernist photography and his pictures have been so widely reproduced in all kinds of publications and reference books that you might think there was nothing left to say.

Yet the show makes two indelible impressions. First, it illuminates photography's transition from an attempt to become art by imitating something else, usually paintings or graphic prints, to a full-fledged art form in its own right.

Weston entered the profession during the advent of pictorialism, a practice that created mood through fuzzy focus and the use of soft-toned platinum and palladium printing papers.

Pictorialism today appears overly sentimental and contrived, but many photographers at the beginning of the 20th century indulged in it because it was commercially popular.

Weston began his career as a portrait photographer and would continue to earn a living that way well into his career. One section of the Michener show consists of small, sharply defined portraits of artists and writers such as D.H. Lawrence, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco.

Yet after he adopted a modernist outlook in the early 1920s, Weston was more concerned with formalist effects and ideas such as high contrast, patterns, and the interaction of corners and edges.

We can see him shifting gears in a 1921 platinum print called A Sunny Corner in the Attic. The ostensible subject is a man with a pipe, but he's almost a prop. Weston's real interest is how intersecting planes generate pronounced contrasts of light and dark, as in a cubist painting.

Michael Mattis once told an interviewer that he saw parallels between Weston and Picasso, in that the work of both can be categorized by distinct periods.

(One could posit a similar comparison in their personal lives; each had an early wife and a late one, with a succession of lovers and muses in between.)

The exhibition reinforces this notion by presenting Weston's photographs in thematic sections, particularly the famous still lifes of bell peppers and cabbage leaves of the 1930s.

There also are images from his extended trip to Mexico in the mid-1920s with photographer and lover Tina Modotti, late landscapes made on the mid-coast of California, where he lived, and finally the famously elemental nudes, which typically reduce the body to a series of curves, planes and shadows.

The model for the most iconic of these was Charis Wilson, who met Weston in 1934 when she was 19 and he was 48. Some of the images he made of her reprise the stripped-down purity of still lifes such as Two Shells, made in 1927. Wilson married Weston in 1939 and they divorced in 1946. She died in November at 95.

Weston had begun to investigate the nude as early as 1909, when he photographed his first wife, Flora Chandler. He pursued this genre in earnest in the 1930s, especially after he met Wilson - Triangular Nude of 1936 may be his most-quoted image of her.

Oddly, while his nudes are sensual they aren't especially erotic, no more so than his famous studies of peppers. Six of these images are in the show, including the divinely muscular and luminous No. 6, which recalls a famous Greek sculpture called the Belvedere Torso, and his silvery-ribbed cabbage leaves.

All these images celebrate the sublime architecture of nature, accentuated by meticulously regulated lighting and a precisely calculated point of view.

Even Weston's late landscapes of the late 1930s and '40s, which began by giving the viewers more descriptive details, are most powerful and eidetic when they concentrate on one or two patterns or forms as in Sandstone Erosion, Point Lobos, and Buzzard on Dry Lake of 1937, which evokes similar works by Frederick Sommer.

For me, Weston isn't so much Picasso behind the lens as Brancusi. Early intimations of the Romanian sculptor's sublimely reductive forms include Chambered Nautilus of 1927 and, even more to the point, a side view of a bedpan standing on edge, a utensil transformed into a modernist totem.

Weston's gift was the ability to locate and amplify the quintessence of ordinary objects and situations - to see profoundly rather than superficially, or worse, not to notice at all. It's this gift that "Life Work" passes along to yet another generation of museum visitors.

Art: American Master

"Edward Weston: Life Work" continues at the James A. Michener Art Museum, 138 S. Pine St., Doylestown, through March 28. Hours are from 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Tuesdays through Fridays, from 10 to 5 Saturdays, and from noon to 5 Sundays. The museum is open until 9 p.m. on First Fridays. Admission is $10 general, $9 for seniors, $7.50 for college students with I.D., and $5 for visitors ages 6 to 18. Information: 215-340-9800 or www.michenerartmuseum.org.

EndText