Art: Delicate, seductive Bengali embroidery

Kantha textiles, with functional and ritualistic uses, are woven into a culture.

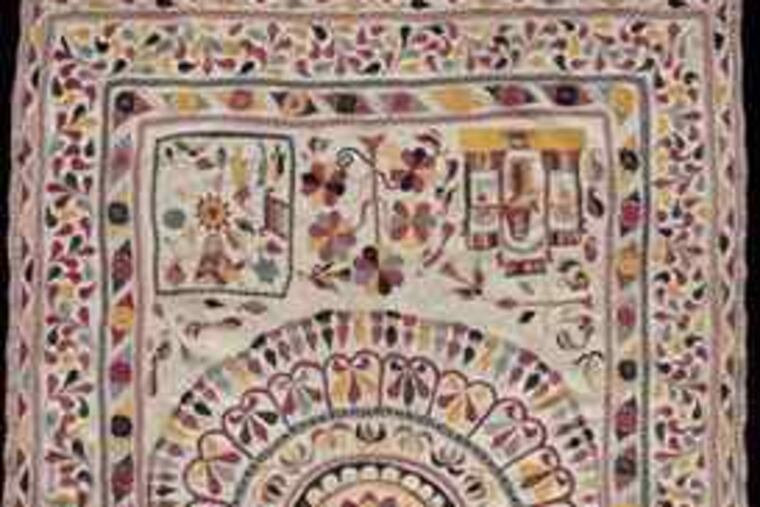

Kanthas are among the most beautifully elaborate and seductive textiles one could hope to see in any museum, but it's exceedingly rare to find them on display in an institution in the United States.

This is because kanthas (slide over the h), besides being structurally delicate and susceptible to damage from prolonged exposure to light, represent highly specialized, non-Western cultural and aesthetic values.

They are intricate embroideries that vary in size from tea towel to bedcover, made in Bengal, a region now split between eastern India and Bangladesh.

Traditionally created by women from worn or cast-off domestic fabrics, they are in that sense like the quilts sewed by generations of American women. The multilayered kanthas are even commonly described as quilts, even though they're not filled with batting.

In Bengali homes, kanthas are used in a variety of ways - functional, ceremonial, and ritualistic. Hindus and Muslims use small ones to cover food and gifts at weddings, as prayer mats, tomb shrouds, pillow covers and carpets, as seating for honored guests, or, most logically, as blankets.

The fact that kanthas have been so thoroughly embedded in Bengali culture for centuries makes them deeply resonant as art.

They're not simply decorative accessories or by-products of leisure activity, as art so often is in the West. Kanthas embody fundamental cultural and religious traditions that have survived colonization and even the partition of Bengal.

In the context of an art museum, it's their enchanting aesthetic qualities that command one's attention and admiration. Intricate designs, soft colors, and, especially, meticulous needlework impart to kanthas their prodigious detail and distinctive textures.

The convergence of two exceptional collections makes an exhibition of kanthas at the Philadelphia Museum of Art a signal event. Forty-six splendid examples of this exotic folk art have been put on view in the museum's Perelman building through July 25.

The show brings together the museum's own kanthas, given and bequeathed by the late, legendary scholar Stella Kramrisch, former curator of Indian art, and a collection assembled between 2000 and 2003 by Philadelphians Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz - he a prominent local lawyer and longtime museum trustee, she a well-known ceramic artist and cofounder of the Clay Studio.

On the occasion of this show, they have given 29 of their 33 kanthas to the museum; the other four are promised gifts. Besides Indian textiles, the Bonovitzes also own a premier collection of art by such untutored artists as James Castle and Martin Ramirez.

The kantha exhibition comprises 46 pieces, 29 collected by Kramrisch and 17 by the Bonovitzes. While the two collections are integrated thematically in the exhibition, as the accompanying catalog demonstrates they're a bit different in character.

(The catalog illustrates the collections separately, each in its entirety; the Kramrisch collection consists of 52 pieces.)

Stella Kramrisch, who lived and taught in India for about 30 years before coming to the Art Museum in 1954, began to collect kanthas during the 1920s. She gave some to the museum in 1968 and bequeathed the rest after she died in 1993.

These kanthas are generally from the 19th and early 20th centuries, with the majority being in square formats about the size of a standard card table. The designs, usually organized around a dominant central motif like a lotus flower, are dense and suffused with Hindu narratives. The corners are often anchored by prominent paisley shapes (bent teardrops).

The Bonovitz kanthas tend to be larger, rectangular in format, and more individually free-form in design. Art Museum curator Darielle Mason characterizes them as "lively and fabulously quirky."

One senses that the women who made the Bonovitz quilts were less constrained by tradition and more inclined to indulge personal expression. One, for instance, consists of a geometric grid of square boxes filled with colored roundels, a scheme widely divergent from the norm.

Kanthas are repositories of memory, not only in their imagery and their evocation of family rituals but even in the fact that they're made from recycled materials, particularly worn saris, which are picked apart for their colored threads.

The white ground cloths, especially of older quilts, are often woven from handspun cotton thread, but machine-woven fabrics were also used.

Both the Kramrisch and Bonovitz quilts typically employed a limited but pleasingly harmonious palette dominated by red and blue (indigo is a major crop in Bengal), with some yellow. The dyes can be natural or synthetic.

The materials were worn and faded when the embroidery began, which partially accounts for the relatively narrow tonal range.

Ultimately, the granular delicacy and density of the embroidery - the thousands of stitches in each quilt - make a typical top-end kantha a masterpiece of world art. The simple running stitch, which produces a rippled corduroy effect in the ground, provides the foundation, while pattern-darning stitches fill in the outlines, sometimes dozens of them in a single piece.

This is one exhibition in which reading all the labels is useful, otherwise most of the symbolism will remain obscure. Even at the material level, however, the magnitude of the skill and dedication involved in making even a small kantha are often astonishing.

With one exception, and typical of true folk art, the pieces aren't signed or attributed to individuals. Nor, with two exceptions, are they dated. (One of the Kramrisch quilts is dated 1875 - it's the only known dated example of a kantha.)

The tradition began to weaken in the mid-20th century after the partition of Bengal between India and Pakistan. In the late 1970s, after East Pakistan became the independent nation of Bangladesh, the craft was revived commercially with the creation of workshops in which women produced kantha-inspired fabrics for the luxury market at home and abroad.

While this industry has provided employment for women and kept the kantha aesthetic alive, it's no substitute for the authentic art presented in this exhibition, not least because the historically vital symbiosis between the images, artisanship, and daily life has been severed.

Art: Bengali Treasures

"Kantha: The Embroidered Quilts of Bengal" continues in the Perelman building of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Fairmount and Pennsylvania Avenues, through July 25. Hours are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesdays through Sundays. Admission: $7 general, $6 for visitors 65 and older, $5 for students with ID and visitors 13 through 18. Information: 215-763-8100, 215-684-7500 or www.philamuseum.org.

A related exhibition, "Arts of Bengal: Wives, Mothers, Goddesses," continues in Gallery 232 of the main museum building through July.

EndText