Art: Paintings from a meticulous illusionist

A Brandywine River Museum show focuses on the trompe l'oeil works of John Haberle.

Illusionism was a passing fancy in American art, an enthusiasm for visual trickery that seems to reflect the spirit of its time, which was roughly the last two decades of the 19th century. Although it was something of a sideshow, it continues to pop up now and then, not only in painting but occasionally in sculpture.

An exhibition of illusionistic painting - usually referred to by the French term trompe l'oeil - at the Brandywine River Museum reminds us that the Philadelphia region was a center for this kind of art. John Frederick Peto lived in Island Heights, N.J., next door to Toms River. George Cope worked in West Chester and Jefferson David Chalfant in Wilmington.

They and William Michael Harnett, an Irish immigrant who began his career in Philadelphia, were the leaders of the movement, and are so remembered today.

The subject of the Brandywine show, however, is John Haberle, who lived and worked in his native New Haven, Conn. He was arguably the most meticulously precise of the illusionist painters, the one most dedicated to the idea of creating images whose appeal derived entirely from their startling mimicry.

This was most readily achieved with subjects that were essentially flat - items such as currency, postage stamps, newspaper clippings, shipping labels, and photographs.

The Haberle show, organized at the New Britain Museum of American Art in Connecticut, is small, only 14 paintings and five drawings. The Brandywine museum has augmented these with a group of illusionist pictures from its collection, by such artists as Cope, Chalfant, Harnett, Peto, De Scott Evans, and Alexander Pope.

This conjunction not only provides a more expansive view of illusionism, it allows visitors to distinguish between pure sleight of hand, which was Haberle's strength, and amplified still-life realism that was more than one-dimensional.

The two types of painting often use similar subjects traditionally identified with illusionism, such as printed matter, dead game and hunting paraphernalia hanging on a door, musical instruments, and smoking materials. Besides being directed at bourgeois taste, illusionism also was intensely masculine.

We can see, though, that some of these pictures, such as a small Harnett still life or Cope's The Hunter's Equipment - his version of Harnett's iconic After the Hunt - are more complex symbolically and narratively than most of Haberle's work.

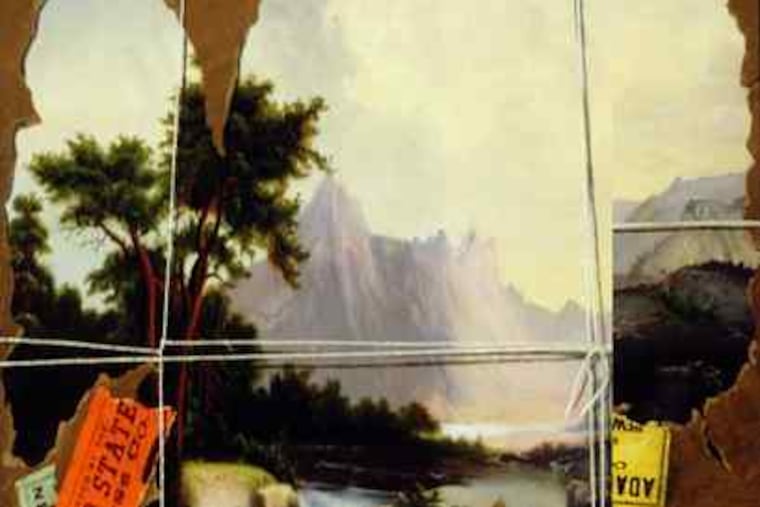

Only about 40 trompe l'oeil paintings by Haberle are known, which probably accounts for the modest size of this exhibition. However, there's enough here to confirm his considerable skill, exemplified not only by four images of currency, but by two pictures of partially obscured "canvases" whose paper wrappings have been "torn in transit."

Haberle, who lived until 1933, may be the least known of the first-rank illusionists, possibly because his images consistently lack any hint of the emotional resonance one finds in Peto or Harnett. They might delight the eye, but there's little in them for the heart and mind.

This could stand as an indictment of illusionism generally - mostly technical flash, little intellectual substance. The formula might have delighted the Victorians, but today's art audiences are, one hopes, a bit more sophisticated.

Woodmere carries on. Since last fall, the Woodmere Art Museum in Chestnut Hill has been muddling along without a director or a curator. One wonders how this is possible, yet the remaining staff, by drawing on the permanent collection and working with guest curators, has been able to keep the galleries lively.

Recently, two new exhibitions joined the Philadelphia Sketch Club tribute on the balcony (through Jan. 2) - a survey of local narrative painting called "Philadelphia Story" and two collections of prints related to "Philagrafika 2010" and a monographic show for Shelley Thorstensen.

In the words of Sarah Roche, guest curator for "Philadelphia Story," the city's rich native tradition of image-based painting instigated a return to figuration after pure modernism lost its momentum in the 1960s. All 17 artists in the show work figuratively, have ties to Philadelphia, and have studied or taught at one of the city's art schools.

Many have become recognized in the city, or beyond. They include Sidney Goodman, Frank Hyder, Jane Irish, Susan Moore, Kate Javens, Rob Matthews, and Ira Upin.

Roche (who might have resisted the temptation to slip one of her own paintings into the hanging) has assembled a potpourri of approaches to figuration, which, as one can intuit from even this small sampling, are almost endless.

Given the lack of a dominant theme, perhaps the show's most useful contribution is the way it demonstrates how figuration has evolved and adapted itself to changing times, how painters have devised imaginative ways to use the figure conceptually.

Shelley Thorstensen's exhibition, "Counterpoint: The Leap from Vision to Print," consists of 31 prints, color and black-and-white. These are definitely not figurative or narrative; the closest I can come to a general characterization is romantic abstraction.

The artist describes them as "a direct expression of consciousness, as in a feedback loop in which the bilateral symmetry of the plate/the print directly reflects my physical/mental imprint. I feel myself looking at myself in a mirror, psychologically facing myself while working."

The prints are for the most part palpably emotional effusions; some of the color prints, such as Eating Light and Repeat After Me, are intensely lyrical and poetic. One can readily believe that the artist is deeply engaged - not only with the images that emerge as she works, but with the process of making them.

One is particularly impressed with Thorstensen's mastery of media. Many prints involve multiple processes, including etching, mezzotint, lithography, relief, screen printing, woodcut, and chine collé - just about every graphic process known.

The ease with which she combines these processes and exploits their individual strengths gives her prints uncommon presence and, more often than not, transcendent beauty.

Art: Painted Illusions

org.

EndText