Art: A memorial to a great gallerist

Marian Locks has been called an earth mother to Philadelphia's art community.

Art dealers - many now call themselves gallerists - rarely become legendary. A new biography of Leo Castelli by Annie Cohen-Solal reconstructs in loving detail the life and times of one who did.

Castelli not only created an international market for American contemporary art, he became as integral to the art history of the last half of the last century as the artists he championed, especially Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg.

The publication of Leo and His Circle intersects with a Philadelphia event honoring a beloved and respected local dealer who, in her own way, was largely responsible for instigating a fertile and exciting period in the local art community.

Marian Locks, who died Feb. 26 at age 95, is remembered by artists here and elsewhere, especially those involved in the feminist movement, as a tireless and enthusiastic advocate for art and, more important, as a friend. While she didn't achieve Castelli's level of celebrity and influence, she became a Philadelphia institution - if you will, a legend.

The event in her honor is a memorial gathering at Locks Gallery Monday afternoon. It's private (by invitation) - which, considering how many people knew and admired her, seems a pity. But then, space is limited.

As I began to read the Castelli biography, I was struck by several parallels between their lives. He didn't open his first gallery until he was 50. Locks took the plunge in 1968, in a narrow sliver of a space on Chestnut Street, when she was 54.

Both succeeded because their early lives prepared them for the moment. Both were involved in art as collectors, and, most important, both loved art and artists. This was noticeably true for Locks, who has been described as an earth mother to the city's art community, a generous nurturer both of artists and young collectors.

In a departure from the norm when she started, Locks made her mark by supporting local talent. Over more than four decades, the gallery has built up an impressive roster, from Tom Palmore and John Formicola to Warren Rohrer, Murray Dessner, Thomas Chimes, Edna Andrade, James Havard, Elizabeth Osborne, and Diane Burko.

Locks' gallery blossomed after she moved to a larger space on the second floor of 1524 Walnut St. in 1971. During the 1970s, she staged cultural events there, such as poetry readings, that attracted participants from New York.

A supporter of the feminist agenda as it related to the arts, she was a key player in a 1974 event called Philadelphia Focuses on Women in the Visual Arts. Also during the '70s, she convinced local corporations that patronizing local artists was both a civic virtue and good for business.

Her solicitous regard for her artists revealed itself in another way, when she opened a satellite space on lower Arch Street where she could show work that was less commercially viable than the painting and sculpture usually featured on Walnut Street.

In 1990, the gallery moved for the last time, to an elegant building on the southeast corner of Washington Square formerly occupied by book publisher Lea & Febiger. Over the last two decades, under the direction of daughter-in-law Sueyun Locks, the gallery has shown more work by nationally known artists while retaining a solid connection to the city through artists such as Burko and Osborne.

The quality that endeared me to Locks was her professional reserve. She was always available for questions about her exhibitions, but she never tried to press her viewpoint on me.

As a committed lover of art for its own sake, she presumed that eventually what she was showing would speak to me. If it didn't, the loss was mine. Her role was that of friendly cicerone, not of aggressive deal-closer.

Locks' view of her calling was humanistic and people-oriented. Perhaps that's why her gallery persists, while many others have come and gone since she opened 42 years ago.

Regardless of how long it remains in business, its founder will be remembered for her enthusiasms, her refined aesthetic ideals, and especially for the sense of community that made her gallery more than just a place to look at pictures.

"American Masters." As an exhibition title, this could mean almost anything. What it means at Somerville Manning Gallery is an attempt to define a historical context for the artists in which the gallery specializes, namely the Wyeths and others associated with the Brandywine tradition.

Can such vaulting ambition be realized with only about 30 works, given that the permutations of the concept are boundless? Yes it can, if one is willing to put aside thoughts of artists not included. "American Masters" is a handsome and piquant show that contains more than a few delights and surprises.

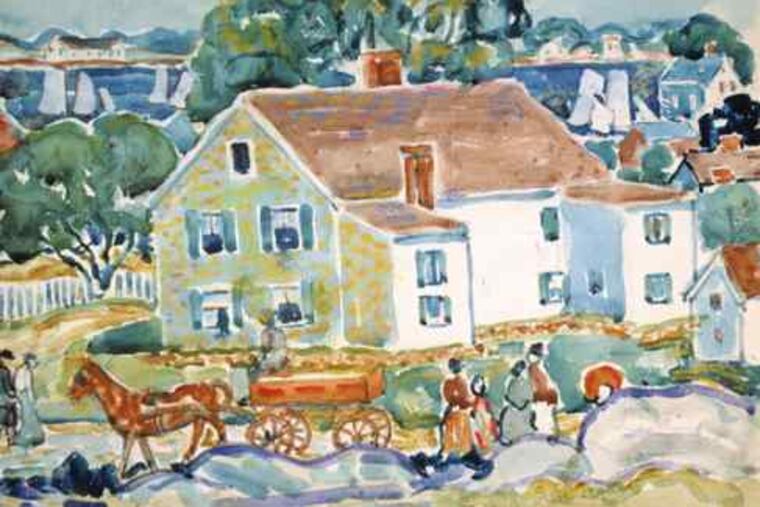

One of these is the fact that the Stieglitz circle, the forefront of the American avant-garde, is well-represented, with works by Georgia O'Keeffe, Arthur Dove, John Marin, and Marsden Hartley. The O'Keeffe is a late abstract watercolor from 1977 that recalls the early works that so impressed Alfred Stieglitz in 1915. For the most part, the images, most from the 20th century and most on paper, are representational. They include a wonderful pair of Charles Burchfield watercolors, one early and one late, in the glorious efflorescence of his late visionary style.

There are three Milton Averys from the 1940s, Red Flowers on a Terrace being the nicest, and three oils by Thomas Hart Benton. Two of these, from the 1920s, capture the artist moving from modernism to the narrative style that made his reputation.

Outside of the theme, striking individual works create points of interest; Alfred Maurer's view of Paris is one; a small Jackson Pollock seascape, in the style of Alfred Pinkham Ryder, is another. One section of the installation devoted to the figure features two contemporary studies by Bo Bartlett, a luminour nude by Everett Shinn, a mother and child by Mary Cassatt, and a woman outdoors by Winslow Homer.

At the center of this realist melange sit the Wyeths, Andrew, N.C., and Jamie. Andrew's gradual shift from painterly to hard-edge realism emerges in the contrast between Burled Oak and Deserted Light. N.C.'s landscape with barn and Jamie's view of a meadow typify the quiet, bucolic romanticism of Brandywine country.

Disparate threads, perhaps, yet they all come together harmoniously in a perfectly measured installation that encourages visitors to contrast, compare, and, above all, to savor distinctive voices for themselves.

Art: American Masters

"American Masters" continues at Somerville Manning Gallery, 101 Stone Block Row, Greenville, Del. (next to the Hagley Museum) through June 5. Hours are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesdays through Saturdays. Information: 302-652-0271 or www.somervillemanning.com.

EndText