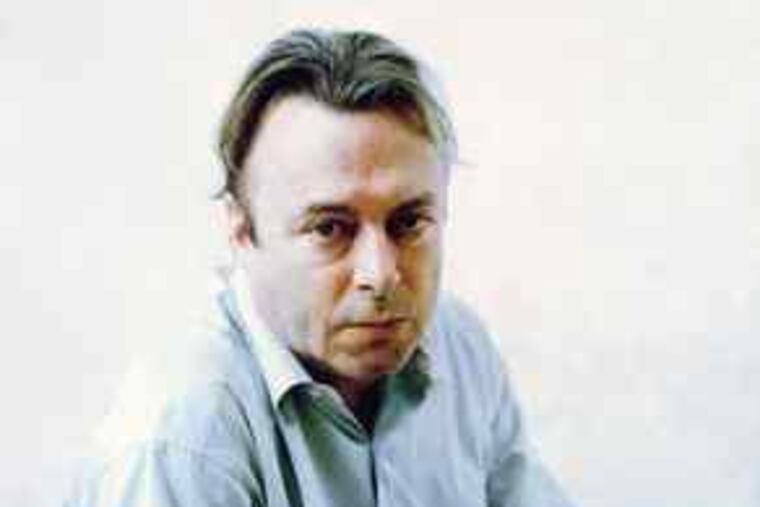

Interview with Christopher Hitchens, author of "Hitch-22"

Anglo-American polemicist, literary critic, and political wag Christopher Hitchens has been called, usually to his great dismay, America's last public intellectual, a contrarian who philosophizes with a hammer, and a political gadfly.

Anglo-American polemicist, literary critic, and political wag Christopher Hitchens has been called, usually to his great dismay, America's last public intellectual, a contrarian who philosophizes with a hammer, and a political gadfly.

Hitchens, whose books include Thomas Jefferson: Author of America and God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything, will discuss his new tome, Hitch-22: A Memoir, Tuesday night at 7:30 at the Free Library of Philadelphia's Central Library, 1901 Vine St.

On Monday, while waiting for a flight to Miami at Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport in Arlington, Va., Hitchens, 61, talked by cell phone about his life, his politics, and his distaste for religion.

Question: Why write a memoir now? Hope you don't plan to shuffle off this mortal coil anytime soon . . .

Answer: Why now? I turned 60 [last year], which means that you are in fact beginning to look over your shoulder a bit. . . . You realize it'll all be gone.

Q: The title, Hitch-22, evokes Joseph Heller's famous novel Catch-22, which suggests much of life is a lose-lose proposition. Is being Christopher Hitchens a trap? A paradox?

A: I am identified with a group of people whose main principle is that of doubt and adamant skepticism. . . . This rationalist commitment puts us in opposition to modern totalitarians, the ones who say . . . the truth has been revealed to them. Opposing that mob has been the principal cause of my life.

Q: Why is that a catch-22? Aren't the rationalists winning?

A: I'm a pessimist. My first book was called Prepared for the Worst. One of the things you realize if you give up fundamentalism is that there are no final victories in the battle against hypocrisy and stupidity and superstition.

Q: You shocked many of your colleagues by supporting the Bush administration's decision to invade Iraq. Any regrets?

A: No. Iraq is clearly better than it was under the private ownership of Saddam [Hussein]. . . . It's the only country in the Arab world that has free elections and . . . the only place where the Kurdish people, the largest group of people who have no state of their own, have an autonomous region of their own.

Q: Security or freedom? Have we given up too many civil liberties in the war on terror?

A: I'm a great admirer of Abraham Lincoln, but I've never had it pointed it out to me that his abolition of habeas corpus helped him win the Civil War. . . . It's not an easy question, but I do think President Bush went too far, that's why I was a member of the ACLU's class action suit against the White House's illegal wiretapping.

Q: Is there any point in debating political ideals in an age when business interests exert so much power over the government?

A: Is it quixotic? I know those things are true, but I carry on doing it. I still go on TV to be dumbed down. . . . [But] some of the feedback I get from people suggests there are people who like seeing someone who isn't part of the media's abysmal carnival of cliches.

Q: You moved to America in 1981 and applied for citizenship shortly after the Sept. 11 attacks. Why prefer America to Britain?

A: The American Revolution got rid of the established church and the monarchy, which the British still have. The Constitution [includes] the Bill of Rights, and it said these documents are subject to revision. . . . And as an American, you are invited to take a part in that experiment.

Q: You're an outspoken atheist who frequently debates religious thinkers. Why is religion so important to you?

A: Because it's the original subject, humanity's first attempt to make sense of things. It precedes philosophy, science, medicine, and free inquiry. It comes from the extreme barbarous childhood of our species, but it deserves respect.

Q: Any advice you'd give President Obama?

A: I sometimes think that he thinks that many disputes and difficulties in the world arise from misunderstanding and failure to translate between cultures. I don't. They arise from irreconcilable differences.

The difference between our system and that of the Islamic Republic of Iran is not the result of a cultural misunderstanding. . . . it's the result of an aggressive, totalitarian regime that seeks confrontation. . . . But I think [Obama] will find that out eventually.

Q: Would you like to have tried another occupation?

A: No, because when I was very small, I understood that I had to write, that there was nothing else for me. I didn't choose it, it chose me. . . . But, I've always been very drawn to diplomats. I think it would be a very honorable profession.