Art: 'Late Renoir' show intrigues at Art Museum

'Late Renoir," at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, is one of the most intriguing and vexing exhibitions to surface here in many years.

'Late Renoir," at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, is one of the most intriguing and vexing exhibitions to surface here in many years.

The show argues forcefully that the paintings produced by Pierre-Auguste Renoir in the last three decades of his life - he died in 1919 at 78 - are a crowning achievement.

There's persuasive testimony for that conclusion from many sources, including Henri Matisse and Albert C. Barnes. Barnes owned more Renoirs than anyone needs (181) and considered Renoir and Paul Cezanne equally important as precursors of modernism.

Through 79 paintings, sculptures, and drawings by Renoir and 13 works by Matisse, Picasso, and other early modernists, the show offers generous encouragement for a positive critical reassessment of Renoir's final decades.

Yet there's also considerable evidence here to reject the idea that Renoir somehow served as a pathfinder for artists such as Picasso and Matisse, both of whom admired him. In his final decade in particular, the onetime impressionist master became obsessed with creating paradisiacal tableaux populated by pink and puffy female nudes.

The exhibition is well-stocked with these. How could it not be? It concludes with The Bathers of 1918-19, which Matisse described as "his masterpiece . . . one of the most beautiful pictures ever painted." Sorry, Henri, but that's an encomium too far. A number of paintings in this show are far more sublime than that one.

It's difficult to square Renoir's neoclassical retrogression with the idea of aesthetic innovation, which is how one normally regards the avant-garde.

Cezanne was a true innovator, a revolutionary who constructed the foundation for cubism. Renoir, by contrast, was an evolutionary, who pushed postimpressionism into an arc that circled back to the Old Masters.

In the process, though, he made some achingly luscious pictures, especially during the 1890s. During the 1880s, he had shifted from impressionism into a more hard-edged figuration, but by 1890 he had moved toward a synthesis of these two styles.

A half-dozen paintings from the early 1890s reveal the sensuous magnificence of this transition, especially Young Girls at the Piano of 1892, which would be my nominee for the apogee of beautiful painting.

In this genre scene - all these introductory images of comely young women show Renoir catering to popular taste - luscious color harmonies combine with a subdued but pervasive light.

The paintings glow internally; the artfully blended colors shimmer seductively. Anyone who enjoys the pure physicality of pigments being deployed to produce optical dazzle and emotional rapture should revel in them.

Matisse was on the right track; when it comes to the joy of painting, no other artist surpasses Renoir, especially at the turn of the century.

The exhibition progresses through several thematic sections that cover pictures of the artist's children; commissioned portraits; landscapes; the Arcadian ambience of Mediterranean France, where Renoir lived during his later life; his love of the decorative impulse; and large nudes and female bathers.

The juxtaposition of individual paintings by contemporaries reminds us that none of these interests is exclusive to Renoir during the early modernist years or incompatible with what more adventurous painters were doing.

One of the more effective of these insertions is Picasso's Woman With a White Hat, a clothed figure but one that reminds us that the most innovative of modern artists also went through a neoclassical period that featured large, awkward female nudes.

Picasso's neoclassicism was far more radical than Renoir's and less evocative of classical ideals, yet in a way it validates the latter's dedication to the theme when art was becoming increasingly more reflective of modern life.

Decoration? No modernist was more lavish in his use of decorative patterns and schemes than Matisse, who might have been influenced by Renoir in this regard. Decorative patterning and effects per se aren't inimical to progressive thinking, so Renoir can be seen to have been slightly ahead of the curve in his extensive use of them.

Finally, nudes, which are the big sticking point when one considers late Renoir. Not only was he devoted to this theme, and in an antique context, but he also created the most extravagantly upholstered and pigmented nudes since Rubens. Nothing looks less modern than the bodies in the paintings that summarize Renoir's philosophy, and which Matisse so admired.

Female nudes remained a staple of early modernism; though that is less true of monumental ones like some of Renoir's, this was clearly a tradition that endured.

Renoir produced some transcendent reclining nudes, particularly Nude on Cushions of 1907 (its pendant, Reclining Nude of 1902, suggests that he didn't always paint winners) and Reclining Nude of 1903, which redeems the genre all by itself.

In fact, it would be easy to believe that Matisse might have based his famous The Blue Nude of 1907 on Renoir's '03 version. The pose is reversed and Matisse's figure is blocky and angular, but still Renoir's example somehow evokes it.

If Renoir did indeed link the past to the innovations of the early 20th century, then Matisse would appear to have been the primary beneficiary. Consonances between him and Renoir receive more attention in this show than allusions to any other artist, except perhaps sculptor Aristide Maillol, known for his big, bronze female nudes.

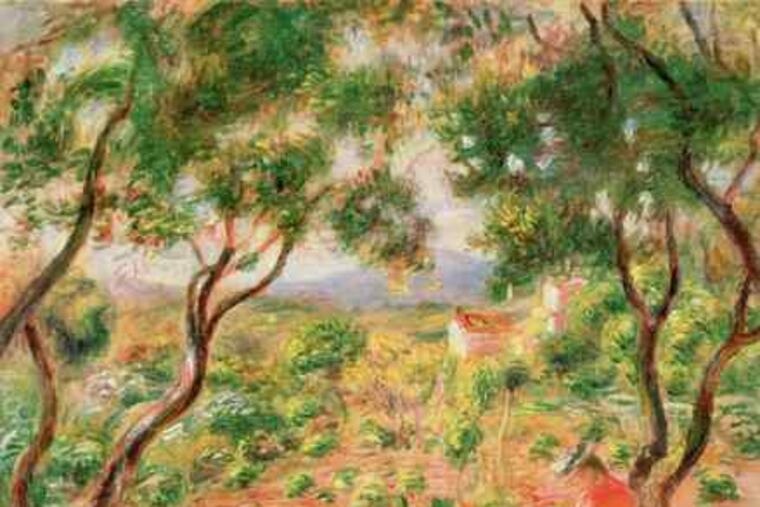

The one aspect of Renoir's late painting that looks plausibly modern is his landscapes, which, because of their fluid gestures, are more compatible with how younger artists were working. Five landscapes are hung with one by Pierre Bonnard, also known for female nudes. In this company, Renoir fits comfortably.

Ultimately, it doesn't matter whether Renoir was a close comrade-in-arms of Cezanne's or just an exceptional colorist revisiting Old Masters like Rubens. I still can't fully accept some of his anatomically distressed, and distressing, nudes - heads too small, thighs too massive - his plethora of rosy cheeks, and his saccharine optimism.

Yet I admire his indomitable will to create in the face of crippling disability, his mastery of modeling and color in paintings such as Two Girls Reading, and his ability to evoke, in a manner very different from Matisse, luxe, calme et volupté.

If you're in the mood for a soothing day with some transcendently gorgeous brushwork, "Late Renoir" is your ticket.

Art: Renoir in Maturity

"Late Renoir" continues at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 26th Street and the Parkway, through Sept. 6. Exhibition hours are 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesdays through Thursdays, 11 a.m. to 8:45 p.m. Fridays, and 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays. (The building opens at 10 weekdays.) The museum will open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. on two Mondays, July 5 and Sept. 6.

Admission is by dated and timed ticket, $24 general, $22 for seniors, $20 for students and visitors ages 13 to 18, and $14 for visitors ages 5 to 12. Discounted tickets at $19 are available through July 16 for 3 and 3:30 p.m. weekdays. Tickets can be purchased at the museum, by phone (215-235-7469), or online (www.philamuseum.org). Service charges apply to phone and online orders. Information: 215-763-8100, 215-684-7500, or www.philamuseum.org

EndText