Art: Vogels' challenging, adventurous collection

Shows in Philadelphia and Delaware are part of their "Fifty Works for Fifty States" gift.

To embrace the art of ideas, a collector has to be able to think creatively, consider alternatives, and remain open to the experimental and the unexpected. This Dorothy and Herbert Vogel have achieved far beyond the norm for close to half a century.

The Vogel collection of nearly 4,000 works of contemporary art covers significant developments beginning in the 1960s and is remarkable not only for its breadth and adventurousness but also because it was largely financed by Herbert's salary as a postal clerk. (The New York couple lived on Dorothy's salary as a librarian.)

What the Vogels have done with this massive archive of art defines admirable - they have donated and promised it to public museums.

The largest chunk, about 1,100 paintings, drawings, sculptures, prints, photographs, and illustrated books, has been transferred through gift and purchase to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, which has mounted two exhibitions of Vogel art, in 1994 and 2002.

An even larger collection, 2,500 works, has been dispersed across the country, with 50 works going to one museum in each state. The fruits of this project, coordinated by the National Gallery, have become evident locally, in exhibitions at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and at the Delaware Art Museum in Wilmington.

(New Jersey's donation went to the Montclair Art Museum, in the northern end of the state, and Maryland's to the Academy Art Museum in Easton, on the Eastern Shore.)

The Vogel collection is often characterized as focusing on conceptual and minimal art, but it ranges beyond those categories into post-minimalism, expressionism, and even, occasionally, representation.

Much of it consists of works on paper, primarily drawings, and nearly all of it reflects a willingness to confront challenging aesthetic concepts and unconventional ways of expressing them.

In other words, the Vogel collection isn't easy going, especially for people who haven't been exposed to art that derives as much, or more, from ideas than from manual dexterity and visual acuity.

Yet the Vogel exhibitions can be stimulating, not only because the art expands consciousness but ultimately because the Vogels' experience provides a role model for people who find unfamiliar art intimidating.

Their story is inspiring because it demonstrates that one needn't be rich or exclusively educated to find satisfaction in, or even develop passion for, the more challenging art of one's time.

The total collection represents 177 artists. In allocating works to the 50 states, the couple tried to create suggestive cross-sections of the full collection.

Consequently, the shows in Wilmington and at the Pennsylvania Academy are similar in spirit but different in their particulars. The Delaware Art Museum features 23 artists while the academy show has 31; only six are in both shows.

Likewise, only six artists, obviously the Vogels' favorites, are in all 50 states, while an additional 15 are in many states. Both numbers indicate that the Vogels often collected in depth, not simply to fill in blanks in an album, as if they were collecting stamps.

The couple live in Manhattan, and they stored their art in their one-bedroom apartment - a good reason, besides financial constraints, for concentrating on drawings and other two-dimensional works. This is perhaps the first thing a visitor to these exhibitions notices, that most of the works are small, and on paper.

The next impression is that there are few, if any, major pieces at either museum (such a judgment being relative). My recollection of the 1994 National Gallery show reminds me that those mostly went to that institution, with whom the Vogels formed a relationship in the late 1980s.

A third, related impression is that many of the drawings in particular are slight, like half-formed thoughts. Some are barely legible, and others consist of only a few marks. This is especially noticeable in two series of watercolor drawings, one set in each museum, by Richard Tuttle, who is probably the Vogels' favorite artist; they acquired nearly 400 of his works.

These so-called "notepaper drawings" - each suite a selection from a larger group - are gestures in watercolor, sometimes so attenuated as to be nearly unreadable. Like classical calligraphy, they're executed in a quick discharge of energy. Tuttle is a master of the seemingly offhand mark that coveys an insight into spatial relationships.

The notebook drawings aren't perhaps the most memorable expressions of his talent, especially compared with several of his hard-edge shapes, but they offer a window into the world of ideas, impulses, and contingencies that so intrigued the Vogels.

Like explorers, they worked in territory that was constantly shifting under their feet. They seem to have been motivated by a desire to learn, to grow, and to become intimately involved with art at the point of creation.

One has to admire their passion, because the art of ideas, at least as it was practiced in New York, often isn't very interesting visually. Sometimes it's banal or boring, or even trivial - you'll find examples in both exhibitions.

Yet if you approach the two Vogel shows as carnivals of ideas and possibilities, of daring or outrageous probes beyond the comfortable certainties of tradition, you should have a satisfying experience.

By all means try to see both shows. They overlap only a little, and by doing so you will be exposed to nearly a third of the artists the Vogels supported.

These artists include some whose names you might recognize - artists like Tuttle, Robert Mangold, Will Barnet, Michael Lucero, and Lynda Benglis, who achieved national exposure - but many, many more that you won't. This tells you that the Vogels didn't collect reputations, they responded to art intellectually and emotionally.

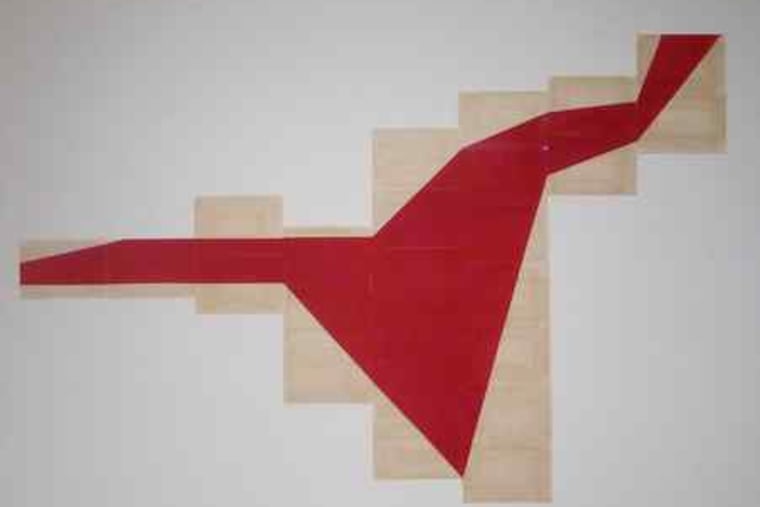

As it happens, a large mixed-media painting by Mangold is one of the premier works in Wilmington, while at the academy a bold Judy Rifka print, an angular red shape on a neutral ground, succinctly defines the nub of their aesthetic.

Going into these shows, it's helpful to know something more about the Vogels than I've told you. Perhaps the most effective vehicle is the captivating documentary Herb and Dorothy, a film-festival award winner that has been shown on PBS. The film plays continuously in the Delaware installation and in the Hamilton building lobby at the academy.

For a more comprehensive picture of the art-for-the-states program, you might consult the project website, www.vogel50x50.org.

Art: Married to Art

"The Dorothy and Herbert Vogel Collection: Fifty Works for Fifty States" continues at the Delaware Art Museum, 2301 Kentmere Pkwy., Wilmington, through Aug. 29, and in the Hamilton building of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Broad and Cherry Streets, Philadelphia, through Sept. 12.

The Art Museum is open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Wednesdays-Saturdays and noon to 4 p.m. Sundays. Admission is $12 general, $10 for visitors 60 and older, and $6 for students with I.D. and visitors 7 through 18. Free Sundays.

Information: 302-571-9590, 866-232-3714, or www.delart.org.

The Pennsylvania Academy is open 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesdays- Saturdays and 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Sundays. Admission is $15 general, $12 for visitors 60 and older and students with I.D. and visitors 13 through 18. Information: 215-972-7600 or www.pafa.org.

EndText