From Air Force to opera to singer-songwriter

On his latest album, The Long Road Home, Dan May has a song called "Bird in the Hand." It contains a line that could easily pertain to the 51-year-old, late-to-the-game singer and songwriter: "You're getting older but holding the dreams of a younger man."

On his latest album,

The Long Road Home,

Dan May has a song called "Bird in the Hand." It contains a line that could easily pertain to the 51-year-old, late-to-the-game singer and songwriter: "You're getting older but holding the dreams of a younger man."

For May, however, "Bird in the Hand" has a more universal theme.

"That song to me is about those people that have a plan and don't deviate from that plan - to a fault," he says at his home in Drexel Hill. "Rather than letting life take you where it's going to take you. . . ."

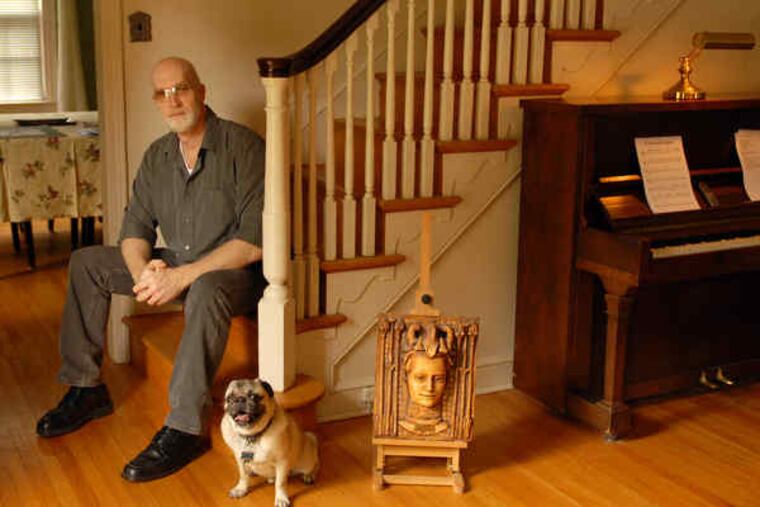

You can't say May hasn't heeded his own advice. So far life - mostly in the form of a staggering series of health issues - has forced the Sandusky, Ohio, native to make a habit of reinvention: He has gone from the Air Force to college to careers as an opera singer and contemporary-ballet dancer and - beginning just four years ago - into pop music. With his recognition on the rise, he headlines a hometown show Saturday night at the Tin Angel.

"Making the crossover from classical music to pop music is not done very often; it's a tough thing," May says. "People say, 'When I heard you were an opera singer, I was expecting something completely different.' "

May's deep, slightly husky voice, reminiscent of Gordon Lightfoot and Richard Thompson, hints at the bass he once was in opera, but with his own music he never aims for any kind of operatic, or even Orbisonesque, grandeur.

The Long Road Home is the latest of his three exceptionally well-crafted and well-written albums of pop music with often rootsy colorings, from mandolin to dobro and fiddle. They're full of insistently catchy, emotionally substantial songs that in another day could have been massive radio hits rather than being limited to the Americana charts.

They also lack arty pretense. "My goal as a songwriter is: 'By the second chorus, [the listener] can sing along with it,' " May says. "I try to make the listener feel like they've heard it before, but it still sounds new to them."

"Artistically, he's exceptional," says Bruce Ranes, program director at the Sellersville Theater, who gave May a headlining gig in May after several opening slots. "He's as good as any of the best national talent we've had here."

Glenn Barratt, a Grammy-winning producer and engineer who coproduced The Long Road Home with May at his MorningStar Studios in Spring House and is collaborating on the follow-up, points to the distinctiveness of May's baritone voice and the quality of his storytelling.

"There are some people that are instinctives and start doing stuff without knowing what they're doing, and they have a knack for it," Barratt says. "There are some people that are schooled. Dan is both. . . . And the combination is really tremendous."

While May wrote songs as a youth, the schooling didn't come until he studied musical composition at Ohio State (after abandoning a journalism major at Bowling Green State University).

He almost never made it there, however. At 20, while serving in the Air Force, the 6-foot-2 May was found to have widespread cancer caused by a rare condition called acromegaly, a hormonal disorder that results from too much growth hormone in the body (think the late pro wrestler Andre the Giant).

He was given three months to a year to live, and after being discharged from the service, he "went home to die." He was saved by a new-at-the-time drug called octreotide, which suppressed the growth of the tumors. (He also had surgery on his pituitary gland that he says required doctors to take his face apart and rebuild it.)

May still must take four injections of the drug a day, but he tries to look on the bright side. Characteristics of acromegaly are a deep voice and prominent features, which helped May in his opera career.

That career began after he won a full scholarship to the Academy of Vocal Arts in 1988 - that's how he arrived in Philadelphia with wife Lisa and son Adam. For a dozen years, he sang with opera companies in the United States and Canada, including several turns with the Opera Company of Philadelphia.

"If you knew the guy, you know that he's of operatic proportions," says Suzanne DuPlantis, cofounding artistic director of Lyric Fest, a local song series, who attended AVA with May and also performed in operas with him. "He's a big guy and he's got these really fantastic looks that read well from the stage, so he was often cast in really interesting parts."

To DuPlantis, May enhanced those roles with his creativity. "So it doesn't surprise me that his creativity is coming out in all kinds of different ways."

May was forced to leave opera when vocal-cord paralysis led to a surgery that didn't take, robbing him of the volume he needed to sing unmiked. So, for three years he worked with the Coleman-Lemieux Dance Company out of Montreal, even performing in the world premiere of a work in St. Petersburg, Russia.

Because the contemporary-ballet troupe's work was more "stylized movement" than dance, May says, he could perform despite having had a spinal fusion in 1993. But pain that eventually led to a hip replacement in 2007 forced him to stop dancing.

"That's when I decided to go back to writing music full time and doing it seriously," he says.

For his first two albums, Once Was Red and Fate Said Nevermind, May collaborated with local producer and multi-instrumentalist Anthony Newett and songwriters such as Stephen Patti and Jerry Guerra. The 2006 debut, featuring "Lights Out in Tupelo," got airplay from WXPN-FM.

"We got great exposure right off the bat, so we decided to start playing live," says May, who originally intended to pitch songs to other artists.

So the piano-playing singer is once again displaying his talents from the stage, as well as in the studio.

"I never got the artistic satisfaction from singing opera that I got from this," he says. "In opera you're singing words and music someone else wrote and countless other singers have done before you. It's hard to really put your mark on it.

"The first time I sat in the dark and listened to my completed CD, that was far more gratifying to me than singing at the Academy of Music.

"Not that I didn't love that. There's no greater thrill than being backstage in costume hearing the overture of an opera when you're the first one out on stage."

But now, "it's all about creating."

"This is definitely where I was supposed to be."