Art: Leonard Baskin's dark vision, deeply felt

A gift of more than 70 works by the sculptor and graphic artist is on view at the Delaware Museum of Art.

Leonard Baskin (1922- 2000) became prominent in American art during the 1950s, even though he was swimming against the tide of modernist abstraction. A sculptor, graphic artist, and printer of limited-edition books, he was a passionate humanist who dismissed such art as morally vacuous.

The late Alfred Appel Jr. quotes Baskin on the subject: "Are we not kin to Goya? Then how can we abide an art that does not bleed when we prick it? The art of our time is an art of cowardice, a triumph of the trivial, a squandering of treasure." It's hard to imagine a more damning indictment.

Appel, who died last year, was a professor of English at Northwestern University for more than 35 years. Besides being a literary scholar, he also wrote books on modern art and jazz.

His admiration for and friendship with Baskin inspired him to form a substantial collection of the artist's work, which he gave to the Delaware Art Museum two years ago. (His sister-in-law, Carol S. Rothschild, is a museum trustee.)

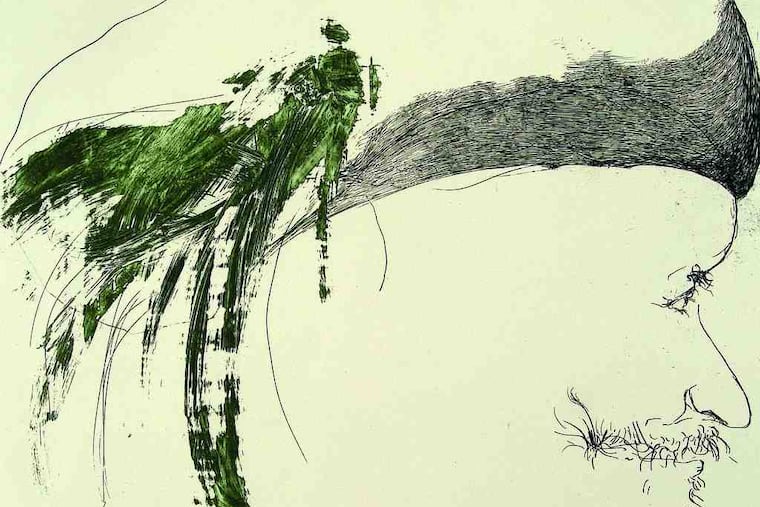

The museum's exhibition of this gift - more than 70 prints, drawings, sculptures and books - indicates that Baskin certainly aspired to match Goya's sometimes gruesome depictions of human failing. As with the Spanish master, the morbid quality of Baskin's imagination produced grotesque hybrids such as a Birdman wearing an Iron Cross on his genitalia.

Baskin's is a dark and melancholy, even lugubrious, art preoccupied with man's fall from grace, tragic lives, and monstrous behavior. For instance, the etching called The Sheriff depicts a Mississippi lawman during the civil-rights confrontations of the 1960s as a nude, flabby, nightmarish brute, the American equivalent of the Nazi Birdman.

The Appel gift doesn't cover Baskin's full career. Most of the works in the show date from the 1960s and early '70s. Many are portraits of other artists, none a contemporary. Baskin seems to have admired those whose lives were troubled or who expressed pessimistic views of the human condition similar to his own.

There are five portraits of Thomas Eakins in the collection, including a large color woodcut, that track Eakins as he ages. There's a bizarre frontal portrait of Rembrandt, neutrally titled Dutch 17th-Century Artist, in which the artist's head is tipped back and viewed from below, making him resemble one of Baskin's signature man-bird hybrids.

Classical and biblical themes are also prominent in Baskin's work, as if to emphasize his estrangement from the artistic mainstream of his time. There are images of Icarus; the poet Homer, his face reduced to eye slits, mouth, and whiskers; Lazarus; and Job, for instance. And there are self-portraits, most notably a 1962 color woodcut.

Baskin described himself as a "moral realist." But don't take realist literally; he was more an extreme expressionist who favored off-center poses, sharp tonal contrasts, and selective details.

One quirk in particular stands out - most of his portraits, including his own, are excessively hairy, which suggests a latent savagery beneath a civilized veneer.

Baskin began his career as a sculptor, but I remember him more as a superb graphic technician, especially in wood engraving, a demanding discipline. The show includes a few engravings from the late 1950s, but most of the prints are etchings and woodcuts, which seem to better suit Baskin's proclivity for expressionist angst.

His artistic temperament perhaps owed something to the fact that he was the son of a rabbi, and that he attended a yeshiva until the age of 16. The moral framework of his art relates closely to that of three other Jewish artists who were influenced by the Holocaust - Jacob Landau, Samuel Bak, and Si Lewen. Exhibitions of their art in the region will be discussed next week.

Mineral Spirits. As an exhibition title, "Mineral Spirits" implies painting, because it refers to the petroleum-based solvent used to thin oil paints. But this exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art presents the work of two sculptors, Anne Chu and Matthew Monahan.

Why "Mineral Spirits"? Frankly, the explanation offered in the exhibition catalog is so forced that one suspects that the artists and curator Jenelle Porter really liked this title because, as Porter says, it sounded "sparkly."

It's enough to say that this small selection of nine sculptures and 10 watercolors and drawings stimulates thinking, particularly about the nature of figuration and how figurative sculptures are traditionally presented, on bases or pedestals.

Both artists use a variety of materials - some traditional, such as wood and cast bronze, and others mundanely utilitarian, such as plastic foam, glass and drywall. Both tend to work by sticking together disparate and contrasting forms, materials and images.

The differences are subtle but distinctive. Chu borrows from antiquity, such as Tang Dynasty tomb figures, and uses color tactically, while Monahan tends to use more unorthodox materials and more radical strategies, such as binding pieces together with cargo straps.

What they both ask us to consider is how figures should be defined. They can be portraits, personal or allegorical, which none of the figures in the show are. They can be symbolically referential - for instance, to history and archaeology - as some of Chu's are.

They can be formalist near-abstractions concerned with surfaces and the relationship of parts, as Monahan's tend to be. And they can be several of these things at once.

The sculptures also can exist simultaneously in the present and in the past; this is perhaps the most intriguing quality that the work of both artists shares. The sculptures are contemporary interpretations of the figure - although in some cases the figure as we know it is almost invisible - but they refer to tradition and history so demonstrably that we can readily recognize connections to what we know.

The long-standing dialogue between figure and pedestal is frequently resolved by blending one with the other. Monahan is especially adept at this; for instance, in Roots for Ryan a carved foam body is strapped between two glass plates. For Indigence, honey, he strapped the figure to the back of the pedestal. In each case, parts usually considered separate become intrinsic to the whole.

Chu's solution for Dancing Girl on Wood is to place the archaic-looking figure atop an abstract pillar made of blocks of raw wood fastened together. In this case, the nominal "pedestal" is as much a sculpture in itself as the figure it supports.

Art: A Gift of Baskins

EndText