In the sometimes strange way that memory works, the seven Martino brothers remind me of Connecticut's seven Lamparelli brothers, who 50 years ago claimed to be America's only seven-brother dance band.

By the same law of probability, the Martino brothers of Philadelphia were undoubtedly the country's only seven-brother artist studio. The Pinto brothers, also of Philadelphia, were runners-up - they fell two brothers short.

The Martinos - born in the late 19th and early 20th century - might not be as famous as other area art dynasties, particularly the Peales, the Wyeths, and the Calders, but, depending on how one defines "artist," they match up well in numbers. They can count at least seven accomplished painters among two generations, as well as several illustrators.

Antonio, the second-oldest brother, and Giovanni, fifth in line, both earned national reputations and were elected to full memberships in the National Academy of Design, in the days when that honor counted for something.

Edmund, the youngest brother, also exhibited nationally, including the biennial of the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington in 1951.

The second generation of Martinos produced three talented painters, Marie Martino Matos, daughter of Antonio, and Nina and Babette Martino, daughters of Giovanni. Their mother, Eva, became a painter after marrying Giovanni in 1948 and over the years has also created a distinctive body of work.

Over nearly nine decades, the various Martinos have become well known locally through dozens of exhibitions, particularly at Newman Galleries in Center City and Woodmere Art Museum in Chestnut Hill, where Giovanni's family had a large show five years ago.

Now the family's accomplishments have been documented in a book written by James McClelland, an arts writer and former director of the Philadelphia Art Alliance, and published by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

Through December, the book's release is complemented by a show of Martino paintings at Newman.

The Martinos: A Legacy of Art combines family history with individual biographies and a chapter on the commercial art studio that the brothers operated for many years in Center City.

The book is generously illustrated with more than 100 color plates of paintings and a number of family photographs that go back to the wedding in 1896 of Carmine Antonio Martino and Clementina Barenello, the progenitors of this remarkable artistic line.

The biographies vary in length according to how prominent each Martino became as an individual artist. McClelland gives Antonio more than a quarter of the 192-page book; Giovanni gets half that.

Although all the brothers produced some art, Frank (who became an illustrator), Alberto, Ernesto, and William are remembered primarily for their contributions to the commercial studio, which had as clients such national firms as Scott Paper, General Electric, RCA Victor, DuPont, and Philco.

McClelland's emphasis on the seven brothers and the studio shortchanges both the women in the family and the second generation - which are essentially one and the same. For example, Eva Martino's paintings are included in the chapter on her husband, Giovanni.

Nina and Babette, who with Antonio and Giovanni are the four best painters in the family, receive short shrift at the end of the book, with shorter biographies and fewer illustrations than their accomplishments deserve.

This seems to be partly because of the book's chronological organization, but I wonder if their being daughters instead of sons also was a factor.

In critical terms, The Martinos is essentially a combination of valentine and family scrapbook; except for the opening chapter, it lacks meaningful context. McClelland doesn't discuss even the four most prominent Martinos in terms of their contemporaries, or what was going on in American art during the decades involved.

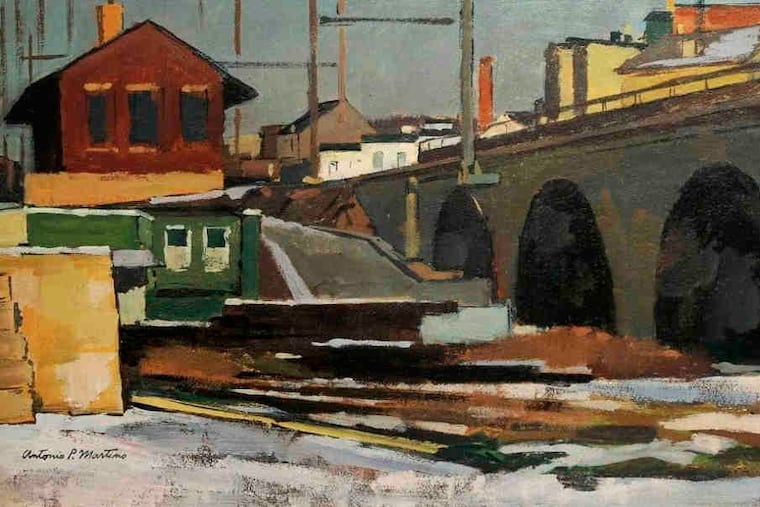

Antonio, Giovanni, Nina, and Babette are, broadly speaking, realists who concentrated on landscapes and townscapes, particularly Manayunk and Norristown. Their art, like that of the Pinto brothers, is often similar to New Hope impressionism and its cognates in being less concerned with narrative than with formal qualities such as massing and contrast of forms and the play of light over surfaces.

In this regard, Babette and Nina have surpassed their father and uncle. Babette in particular has become a master of clarified light, so beautifully realized in the painting at Newman Galleries called The Fall in Norristown.

McClelland avoids any critical discussion of Martino art in favor of resumé particulars such as exhibitions and prizes won. Perhaps he didn't feel qualified to offer such judgments, or perhaps the publisher didn't want to examine the art closely, preferring to emphasize the appealing dynastic story.

The result, for whatever reason, reads somewhat like a school report, more a family Festschrift than an analysis of how these descendants of an immigrant stonemason fit into the broader history of 20th-century American art.

In this regard, a mention of the Pintos, all of whom studied at the Barnes Foundation (Angelo Pinto even taught there), might have been instructive. Also the children of Italian immigrants, they traveled a similar road.

The fact that two such families emerged in Philadelphia - Angelo's daughter, Jody, also became a respected artist - is an improbable coincidence, if nothing else.

McClelland's book is marred by several egregious errors that careful editing should have prevented. The birth years of Nina and Babette are first given correctly as 1952 and 1956, respectively, and then incorrectly, twice, as 1942 and 1946.

The author credits Babette with winning "three prestigious Pew Fellowships in the arts." Unfortunately, the rules of that game allow artists only one; Babette got hers in 2000.

And in a photo on page 137 the seven brothers pose in their commercial studio, but only six are identified.

The Newman Galleries exhibition of more than 50 paintings pretty much reflects the emphases in the book. Antonio receives the most attention with 15 paintings, Babette and Giovanni have 11 each, and Nina, inexplicably, has only four, which misrepresents her standing among the family's more accomplished artists.