A wide range of holdings to mark its 125th anniversary.

Sizable exhibit is just a portion of Bryn Mawr College collection

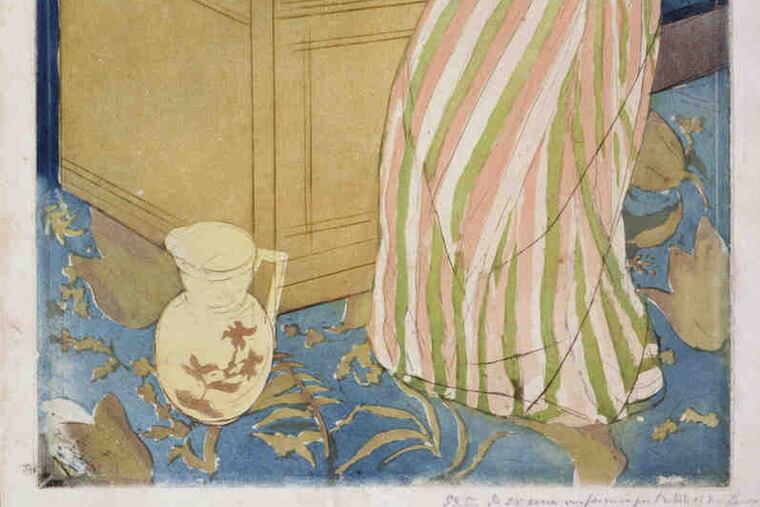

Genuineness and greatness abound in the art exhibition "Worlds to Discover: 125 Years of Collections at Bryn Mawr College." Its aesthetic brilliance, along with the complexity of its message, fills us with wonder.

From far-flung places and various periods - and usually kept under wraps - this collection of the college's art was produced as long ago as ancient Egypt and China and as recently as a 1915 photo by Ansel Adams.

Much is now on view, yet, amazingly, this sizable show represents a skimming - just some of the most significant and beautiful examples from Bryn Mawr's holdings, which are said to comprise 50,000 artworks and artifacts; 50,000 rare books; and several million pages of manuscript letters, diaries, and other documents housed in its major research library that serve as a resource for graduate students and other scholars.

While it's impossible to divide the collection into neat categories, this anniversary exhibit contains nine sections - five devoted to different periods of Western civilization, three focusing on a particular region of the world, and one zeroing in on the link between antiquity and European civilization after 1500. It's heady stuff, complex but very approachable in this format.

Among the readily identifiable works that establish the art collection as major are pieces from the ancient world - the Attic black-figure storage jar and the Attic red-figure plate that have been studied by generations of students; medieval illuminated manuscripts of unusual distinction; and one of the largest collections of books printed before the year 1500. Plus a trove of old-master prints studied in art-history classes, notably the etching Rembrandt Drawing at a Window (1648), and anthropology collections of the Americas with beautiful utilitarian artifacts from the Arctic, the U.S. Southeast, and the Northwest Coast.

The accompanying catalog identifies many generous donors of these treasures. It tells how Center City's Seymour Adelman (1906-85) became Bryn Mawr's single largest donor of books and manuscripts. (I remember him as a Thomas Eakins family friend who was helpful to Eakins' widow, Susan, often driving her to art exhibits in his father's big touring car.) Another of those grand collectors was Bryn Mawr alumna and passionate Africanist Margaret "Margo" Feurer Plass, who also donated to the British Museum and was honored by Queen Elizabeth II for her work. (In early childhood in Philadelphia, her playmates had been sculptor-to-be Sandy Calder and sculptor Charles Grafly's daughter, Dorothy, who became a prominent Philadelphia art critic.)

This exhibition gives the visitor a unique chance to appreciate one distinguished institution's lifelong collecting activity, curated with immense care to demonstrate the astonishing range of its holdings. There could be no more appropriate way in which to honor this Bryn Mawr 125th birthday.

Chester through his eyes

In 105 watercolors of Chester that he painted in the late 1940s and early '50s, Jesse Soifer displayed a realist's awareness of time and place. On view at the Delaware County Historical Society's Museum, this substantial body of work limns street scenes, the waterfront, a boatyard, industrial areas, tidal regions, and the view from the rear of Soifer's house. A few are in black and white.

All present a way of painting from actual observation that is seldom adequately appreciated. The historical society, by accepting the artist's recent generous gift of them and by placing them in context, reestablishes Soifer's place in mid-20th-century painting and drawing. Now a Philadelphian, the artist also is showing recent colorful abstract paste-ups, as fresh and freely done as his savory earlier work.

True grit

Greg Prestegord's 46 cityscapes at F.A.N. Gallery - nearly all of Philadelphia, his hometown - are painted in oil on found wooden panels that he has gouged, sanded, and repainted to capture a sense of urban grittiness. This new work demonstrates his love of paint and an innate sense of structure. Everyday scenes - fences, rooftops, underpasses - are filled with atmosphere you can almost reach out and touch. Prestegord is particularly good when working on an intimate scale, as when painting a distant lineup of cars at a curb as one car turns the corner.

Could such scrupulous, almost photographic, exactitude be the hallmark of naturalism, a step beyond realism? Prestegord takes photos he then uses for reference and doesn't actually paint on site. Does that make him more naturalistic?