Here I am!

On Foursquare and other location-based apps, users check in, link up, earn rewards, court delight. They also jeopardize their privacy.

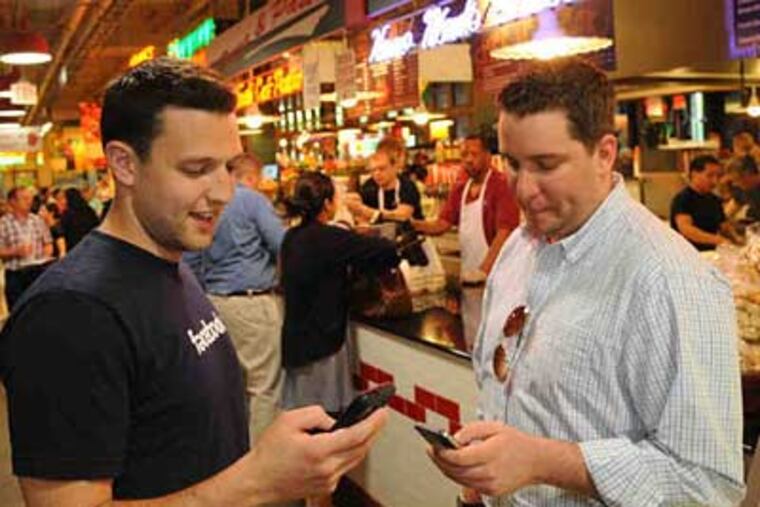

As Jed Singer goes about his day, he reveals his exact location to 100 of his closest friends.

Typically, his digital footprint, broadcast through the location-based service Foursquare, might look like this: 8:05 a.m. Jed S @ Tuscany Cafe. "mmm americano & bagel" . . . 2:31 p.m. Jed S @ Reading Terminal Market . . . 7:14 p.m. Jed S @ Triumph Brewery " . . . head over!"

Any of his friends can then stop by and meet him in person. Or Singer, 25, of Rittenhouse Square, can use his phone's GPS to see who's nearby and issue an invitation. Often he sends out his commentary, or shouts in Foursquare lingo, to his 800 Twitter followers as well.

"Foursquare's appeal in part is this element of serendipity," says Singer, who works in social media marketing. "If I'm in between activities, I can see who's nearby and have coffee."

Like other increasingly popular location-based services, Foursquare is one of the latest must-have geo-social apps, especially for the under-25 crowd. Think of it as a status update focused on the where, rather than the what.

"Check in" to your location and reap the rewards: Spontaneous, in-person encounters, insider information about a business (regarding a Brazilian wax joint, one member wrote: The "older lady is not gentle and has burned me. Everyone else is phenomenal!"), and tailored-to-you deals from merchants (local Dunkin' Donuts rewards the fifth check-in with a free coffee).

Yet not everyone values the chance to "unlock your world and find happiness just around the corner," as Foursquare touts itself. Child-advocacy groups, privacy experts, and a congressional leader or two are apprehensive over the personal information that is captured and then used by marketers and businesses for profit.

"I absolutely have concerns," says Michael H. Fienman, a Philadelphia-based attorney specializing in social media law.

He warns about one potential danger of advertising your location - letting a bunch of folks know you're not home, for example. Last year, the website PleaseRobMe.com garnered attention over its riff on that particular pitfall.

"Once people really understand the privacy implications," Fienman argues, "I don't know how long the location-based services will be around."

For now, however, they are growing faster than a teenager's list of Facebook friends. Since Foursquare launched two years ago, it has ballooned to 8 million members and is adding 35,000 new users each day, according to the New York-based company. The field is crowded with a multitude of players, including Gowalla, Facebook Places, and Google Latitude.

The Pew Internet & American Life Project found that about 8 percent of online adults ages 18 to 29 use a geo-social app. On any given day, the report found, 1 percent of Internet users - millions of people - check into a location-based service.

"Our mission is to make cities and places where people live easier to explore and more interesting to explore," said Jake Furst, Foursquare's business development manager. "A lot of it is about surprise and delight. Every time you check in, you don't know what's going to happen."

Foursquare has built its hip rep on the badges and perks its users earn through a giant scavenger game. Visit 20 pizza shops and earn a virtual Pizzaiolo Badge. Check in the most at a particular venue and become mayor, with privileges.

Ellie Siegel Gibbard, 30, an attorney and business developer for the Pennsylvania Convention Center Authority, has the Jetsetter Badge for check-ins at various airports. "I thought that was cool," she says.

Gibbard also checks others' tips about restaurants and other places even as she leaves her own. "To me it's my responsibility, as a person who experiences things, to share that with the greater world."

This spring, the Greater Philadelphia Tourism Marketing Corporation officially launched its Foursquare presence. The mayor (in Foursquare land) of the Independence Visitor Center got a special message in April from the real deal, Mayor Nutter. The corporation also leaves tips for various Philly-area venues; one pointer about SEPTA's Airport Line at Philadelphia International Airport is its most popular, says social media director Caroline Bean.

"Foursquare is a no-brainer because it's location-based," she says. With its millions of users, "it's beyond the tipping point."

Tommy Up, the owner of the burger joint PYT in Northern Liberties, was delighted that his eatery rocketed to the most-checked-in venue in the city after 30th Street Station and Rittenhouse Square Park. The trick: his brewski giveaway. "We did all this without any advertising dollars," he raves.

In the excitement over collecting tips and earning badges, however, it can be easy to forget about privacy issues.

"Essentially, you're giving a third party a very detailed map of your social life and geographic profile," said Rob D'Ovidio, an associate professor of criminal justice at Drexel University who specializes in technology and electronic crime.

He thinks Foursquare and its ilk are innovative tactics to connect people and to market to them. But he wants fair pay for his information. And an occasional free-beer deal isn't reimbursement enough given the value of an individual's digital footprint to marketers. Ultimately, D'Ovidio expects these businesses to "economize your eyeballs" - that is, sell the information.

Foursquare did not respond to questions on privacy issues. Instead, it pointed to the Privacy 101 section of its website, which explains its user controls. The company is noted for privacy policies that allow users to opt in rather than opt out of information dissemination - a best practice.

Still, Foursquare is collecting information about its members. As Furst said: "Every check-in counts. Foursquare gets smarter and more tailored to you."

So do the company's business partners, who have access to top users' check-in data and trend analytics at no charge, for now.

When children are involved - and many are - the stakes are higher, argues Common Sense Media, a San Francisco-based nonprofit that helps parents manage media in their children's lives. It is lobbying for easier-to-understand privacy statements on social network sites, noting that a poll it commissioned last year showed that more than half of teens do not read the terms of agreement.

The group's online review gave Foursquare an "iffy" rating and recommended it only for those 17 and older. (Foursquare requires users to be at least 13, but because the company does not authenticate ages, younger children could, and likely do, join.)

"It will be all-too-tempting for some kids to attempt making new real-life friends with Foursquare," the review notes. "And with no age limits or predator filters, that could be a dangerous thing to do."

Caroline Knorr, parenting editor at Common Sense, also points out the consumer-focused culture of these services. "Do you really want your kids marketed to all the time? . . . Nobody really knows how these companies are using this information."

Sens. John Kerry and John McCain recently proposed the Commercial Privacy Bill of Rights Act of 2011, which would require companies that gather personal data to offer people access to their information and allow them the ability to block the use or distribution of it.

Members of location-based services, however, consider all the hoopla over privacy overblown.

"If I'm out at night alone, I won't check in on Foursquare," Gloria Bell, 45, of Old City, says of basic precautions she takes to protect herself. Other times, she enjoys Foursquare for the connections it enables. "That ability is its most beautiful side," she says.

For Jed Singer, Foursquare allows him enough control over his check-ins, which he can send out to no one or to as large a group as all of his Twitter followers.

"My father doesn't want anything anywhere," Singer says of the tight rein the older man keeps on his personal information. "To be invisible on the Web is his goal. That's fine. Me, I want a brand on the Web. I want a persona for people to find - not nothing."

Foursquare, for one, is helping build that profile, one check-in at a time.