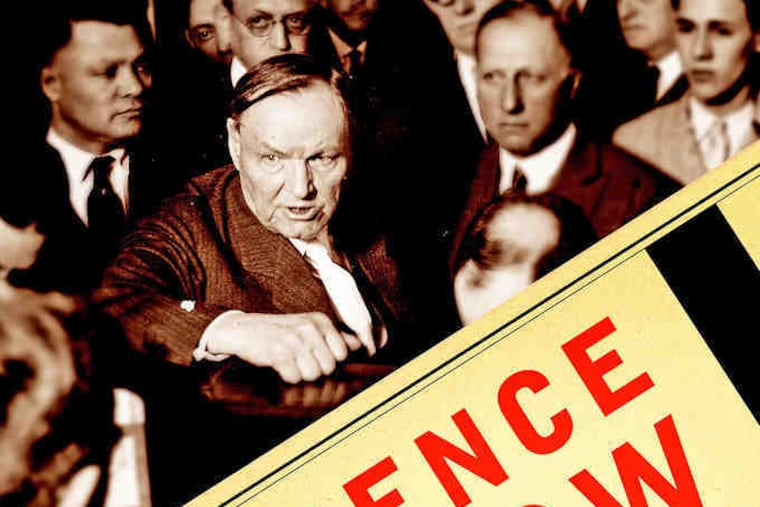

The defender of the underdog

A Clarence Darrow biographer finds the passion and flaws in the renowned defense lawyer.

Attorney for the Damned

By John A. Farrell

Doubleday. 576 pp. $32.50

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by Joelle Farrell

It seemed fitting to finish reading a biography of Clarence Darrow, the famed defense attorney, on Labor Day weekend.

Darrow made his name defending underdogs, including some of the earliest leaders of organized labor. Darrow also defended a mentally ill man who shot and killed the mayor of Chicago, a black family charged with murder after a mob of white people tried to force them out of a neighborhood, and a Tennessee public school teacher who broke the law by teaching evolution to his students.

He also defended less-savory characters. Two of his most notorious clients were Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, teenage boys of wealthy Chicago families charged with murdering a 14-year-old boy. When asked why they kidnapped, molested, and murdered the boy, Loeb told officials, "I did it because I wanted to."

But as journalist and author John A. Farrell (no relation to this reviewer) shows in his irresistibly titled book, Clarence Darrow: Attorney for the Damned, Darrow defended both the righteous and the despised with the same vigor. He believed that even the foulest of crimes could be explained, at least in part, by a person's life experience. He vehemently opposed the death penalty. And just as he defended miners who used dynamite to further their cause of establishing workers' rights, he defended the right of Leopold and Loeb to live, arguing that they were mentally ill and that their youth hindered their judgment.

Of course, Darrow was no saint, and Farrell doesn't shy away from his less-admirable characteristics: his womanizing, his money troubles, and, perhaps most notably, his willingness to bribe a jury, if needed. Darrow was tried for bribery twice in his career, and both times managed to dodge the charge. Farrell, citing correspondences not previously available, shows that Darrow wasn't above the tactic.

And Darrow wasn't a purist; he took some cases for the fame or the fee. Although he had his own moral reasons to take on the Leopold and Loeb case and was asked by the families to defend the boys, Darrow was also excited to be paid well. He was disappointed to receive only $65,000 for his work; he had tried to persuade the families to pay $200,000, Farrell writes.

Long before Leopold and Loeb, Darrow cut his teeth as labor's lawyer. His first union case was defending Eugene Debs, who organized one of the earliest industrial unions (the American Railway Union) in the United States.

Debs was charged when his fellow railroad workers went on strike in 1894. George Pullman, who owned a company that constructed railway cars, slashed his workers' wages but not the rents in the town he built to house them. Railway workers refused to move Pullman cars, shutting down trains across the country. Riots broke out, railcars were burned, and rioters were shot as the federal government moved in to quash the strike. Debs was charged with criminal conspiracy, and the case made it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

"When a body of 10,000 men lay down their implements of labor, not because their own rights have been invaded, but because bread has been taken from the mouths of their fellows, we have no right to say they are criminals," Darrow argued.

Darrow lost the case at the Supreme Court, but he established himself as labor's ally, and through various cases, he laid out a defense for unionized labor.

He represented Pennsylvania coal miners during a strike in 1902, calling to the stand scads of "Dickensian characters" to testify about their harsh lives. One of Darrow's witnesses was a 12-year-old old boy who went to work in the mine after his father died in a tunnel collapse. The boy never received wages because the coal company claimed that the boy's dead father owed the company back rent.

"If the civilization of this country rests upon the necessity of leaving these starvation wages to these minors and laborers . . . or upon the labor of these poor little boys from 12 to 14 years of age who are picking their way through the dirt . . . then the sooner we are done with this civilization and start anew, the better," Darrow said.

One of Darrow's greatest labor victories was beating murder charges against three union leaders accused of conspiring to kill a former Idaho governor. The police had caught the man who pulled the trigger, Harry Orchard, but the prosecution aimed to pin the murder on union leaders William Haywood, Charles Moyer, and George Pettibone.

In his closing statements in Haywood's case, Darrow said, "It is not for him alone I speak. I speak for the poor, for the weak, for the weary, for that long line of men who, in darkness and despair, have borne the labors of the human race."

Farrell's book is fairly long, but it's an enjoyable and surprisingly swift read, even for those with no prior knowledge of Darrow.