Evolution hints at a superbug strategy

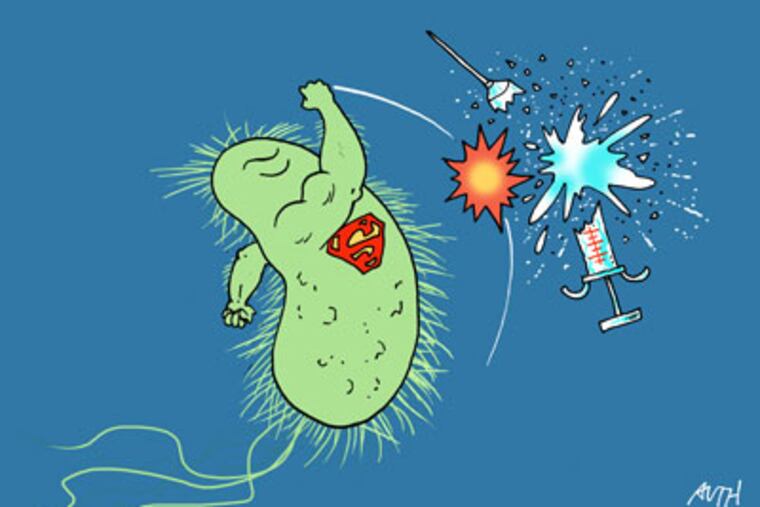

Few notions are as entrenched in medical dogma as the idea of pounding infections with long courses of high-dose drugs. So it came as a bit of heresy this summer when a Pennsylvania State University evolutionary biologist suggested that in some cases a softer blow might actually work better.

Few notions are as entrenched in medical dogma as the idea of pounding infections with long courses of high-dose drugs. So it came as a bit of heresy this summer when a Pennsylvania State University evolutionary biologist suggested that in some cases a softer blow might actually work better.

The biologist, Andrew Read, started his biology career in the 1980s studying plumage in birds, since the colors and other qualities of feathers are connected to a bird's lack of parasites. Then, he realized there was nobody in evolutionary biology studying the parasites.

Now he's part of a budding field known as evolutionary medicine, where his experimental work focuses on the parasites that cause malaria, though he believes the concepts can be applied much more widely - to bacterial infections, TB, even cancer.

Sometimes using full chemical firepower works, he said, and sometimes "you can create this evolutionary monster" in the form of a resistant strain. That happens, he said, when there are already resistant organisms around, in which case the drugs then serve to wipe out their competitors.

Read laid out this idea in June in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Some doctors agree the conventional wisdom should be rethought. "There has been very little if any data to help determine the correct duration of therapy for most diseases," said Neil Fishman, director of the Department of Healthcare Epidemiology and Infection Control at the University of Pennsylvania. It makes sense, he said, that extending a course of drugs also extends the selective pressure on the bacteria to develop resistance.

"The old ideas are based on tradition," added physician Robert Perlman of the University of Chicago. "What's really interesting about Andrew [Read]'s work is that he's looking at infectious diseases from an ecological perspective." That, he said, has been missing from the medical approach.

Read studies malaria in mice, where he has found that a lower dose or shorter course of antimalarial drugs can sometimes work much better than a higher dose when there are mixtures of resistant and nonresistant strains.

That happens, he believes, because the drugs actually help the resistant parasites. A key concept here is that in Darwinian evolution, individuals compete with each other, whether they're animals or malaria parasites. That means that inside an infected person, different strains of malaria parasites are vying for dominance, and a drug will tip the playing field.

A high dose of a drug actually gives resistant strains a huge advantage by wiping out its competitors. "Not only does the resistant guy not notice the drug, but he now has no competitors," Read said.

In contrast, a shorter regimen can depress the population of parasites, helping the patient recover while leaving sensitive parasites to compete with the resistant ones. Such a strategy allows the immune system to finish the job, even if some drug-resistant parasites have appeared.

Some infectious-disease experts see hope for a new strategy in fighting malaria, which is a formidable disease. The once-effective drug chloroquine was rendered useless by the evolution of resistant strains, said Sebastian Bonhoeffer at ETH Zurich, a science university. And there's a risk the current wonder drug, artemisinin, might lose its power. Already, some resistant cases have turned up.

In the long run, an evolutionary approach could save money and lives, Bonhoeffer said. A new drug can cost half a billion dollars or more to be developed, yet little attention goes into prolonging the lives of the drugs we have, and making them more sustainable.

Stephen Stearns, an evolutionary biologist at Yale University, said it makes sense to let drugs and the immune system "gang up" on infections, whether it's the malaria parasite, TB, a staph bacteria, or even cancer cells, since they, too, can evolve drug-resistant strains.

"There's no question one of the places evolutionary thinking can really save lives is in management of antibiotic resistance and cancer chemotherapy," Stearns said.

Bacterial infections can acquire resistance in insidious ways, he said. Different types of bacteria can exchange genes through "horizontal transfer," and so infectious bugs can pick up resistance-conferring genes from normal friendly bacteria, which are also under pressure to develop resistance when patients get antibiotics.

Read's ideas, Stearns said, point to a great potential to improve human health if they can be backed by more experiments.

More work will also be needed to find that perfect "Goldilocks" spot where you're giving a patient enough drug to help the immune system wipe out the infection, and not so much that you encourage a resistant strain to flourish.

Chicago's Perlman said that in both cancer and infectious diseases, doctors tend to think in terms of attacking or waging war. In an evolutionary view, the disease organisms or cancer cells compete against each other. They don't present a united front - and that's something medicine can exploit.

There are other ways evolution is starting to be applied to medicine, Perlman said, including a closer examination of symptoms - some of which may be good for the patient. For example, people with infections often show low blood iron, which doctors used to try to treat with supplements. But what's really going on is that infectious bacteria need extra iron, and the human body has evolved a mechanism for sequestering iron when it senses an infection, thus depriving the bugs.

Today, there's also active research into autoimmune diseases and the so-called hygiene hypothesis, which posits that our immune systems evolved to deal with more germs than we're exposed to today.

The bigger issue is that drug resistance is worsening, said Penn's Fishman. "We need to get an answer because the unfortunate reality of medicine in 2011 is that we are running out of antibiotics and there are few in development to manage the infections we're seeing." If the trend isn't reversed, he said, infections will start sliding back to the preantibiotic era.