On the religious roots of celebrity worship

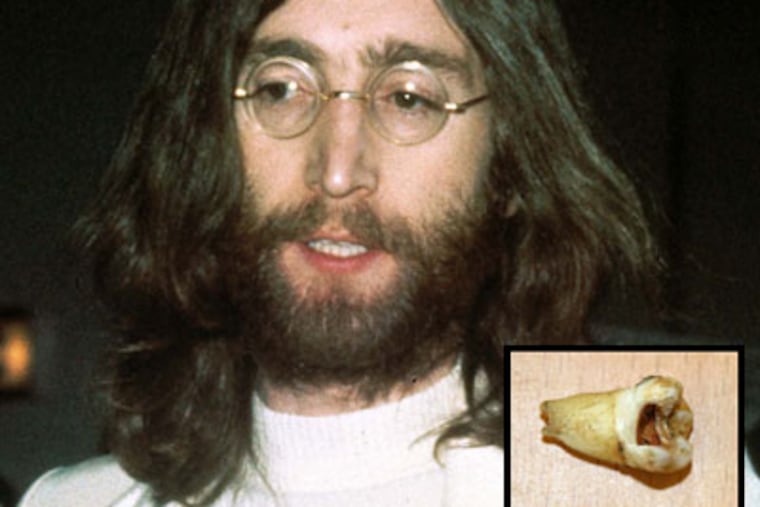

There are absurdities aplenty when it comes to our adulation of celebrities, but few in recent memory have made as many headlines as this one: A Canadian dentist named Michael Zuk paid $31,000 last month for one of John Lennon's teeth. (Lennon had the half-rotted molar extracted 40 years ago and gave it to his housemaid as a present.)

There are absurdities aplenty when it comes to our adulation of celebrities, but few in recent memory have made as many headlines as this one: A Canadian dentist named Michael Zuk paid $31,000 last month for one of John Lennon's teeth. (Lennon had the half-rotted molar extracted 40 years ago and gave it to his housemaid as a present.)

When it comes to celebrity memorabilia, nothing seems out of bounds:

In March, a lock of Justin Bieber's hair fetched $40,668 on eBay.

In other hairy things, a set of James Brown's hair curlers went on the block in 2008. Alas, it fetched less than $400.

There have been more than two dozen online auctions of used Britney Spears chewing gum, some fetching upward of $14,000.

In 2006, Star Trek star William Shatner raised charity money by selling a kidney stone for $25,000.

"Some people desire to have a personal link, however absurd, with power and fame and something glorious and glamorous," says Temple University religion professor Lucy Bregman. "It's a form of magical thinking, something human beings are never likely to outgrow."

Elvis Presley was hip to this. During the 1970s, he'd regularly keep a pile of white towels on stage, use them to mop his sweaty brow, then throw them to the audience as some kind of damp blessing.

Is investing so much devotion - and money - in a tooth all that absurd?

Is it less absurd to make a pilgrimage to Sri Lanka to pay respect to a tooth believed to have belonged to the Buddha? Or to send on tour a bone fragment taken from St. John Neumann, whose remains rest in Northern Liberties?

Zuk's actions aren't all that preposterous, says Emory University's Gary M. Laderman, if we look at our culture of celebrity worship as just that - worship.

"We have instituted a religious culture around celebrities," says Laderman, author of Sacred Matters: Celebrity Worship, Sexual Ecstasies, the Living Dead, and Other Signs of Religious Life in the United States (New Press, 2010).

"It doesn't just function like a religion. It's not a pseudo-religion," he adds. It "is a genuine religious phenomena."

Celebrity-talk is rife with religiosity, Laderman suggests.

Take celebrity itself. In the middle ages it designated a "solemn rite or ceremony."

We speak of screen idols and singers as divas - Latin for goddess - and praise their performances as divine.

Marquee stars and prophets alike entrance people, sometimes to the point of madness. That quality, charisma - from the Greek, "a divine gift" - resides in George Clooney and St. Francis of Assisi, Sean "Diddy" Combs and Moses, Beyoncé and St. Teresa of Avila.

Laderman maintains that the closest historical parallel to celebrity worship is "the early Christian history of the cult of saints." It was a tradition in which relics, sacred objects used to connect with them, played a central part.

Zuk, 49, doesn't exactly worship Lennon. He doesn't make obeisance to him by praying to his tooth. But the dentist does ascribe to it great symbolic power.

"Lennon was one of those extremely important people in history . . . [and] he has such an attraction to people that anything related to him is a big deal," he says from his dental office in Red Deer, Alberta.

Zuk says objects that belonged to Lennon crystalize his ideals, including "his activism for world peace."

Why do people venerate relics - and the people they symbolize? The practice exists in all religions, says Bregman. In Christianity, it goes back to the early martyrs, who gained great notoriety in death because they were executed for their beliefs.

"[Christians] believed that the martyrs' bodies were tainted with a kind of sacred power that could connect them with God," says Bregman.

Saints' bodies became so revered, entire churches and monasteries were built around their graves or housed their remains, says Bregman, whose books include Death and Dying: Spirituality and Religions (Peter Lang Publishing, 2003).

Celebrity was important then, as it is now: Clerics and monks would actively market their church's relics, says Felice Lifshitz, a medieval historian at the University of Alberta. The more famous the saint, the greater authority and power of the church that housed the remains, she says.

Why try to reach God through the intercession of the dead?

Saints triumphed over death because they partook of God's immortality, says historian Patrick Geary of Princeton University's Institute for Advanced Study. Likewise, we partake of it through saints' relics.

A similar symbolic transformation happens to beloved stars after their death, says Geary. Celebrities such as Elvis Presley, Princess Diana, James Dean, and Marilyn Monroe live on through movies, photos, CDs, and memorabilia - the media equivalent of immortality.

"There's a kind of cultural fascination with special people who are marked out for greatness but who die young and often in tragic or violent circumstances," says Geary, author of Furta Sacra: Thefts of Relics in the Central Middle Ages (Princeton University Press, 2008).

Just look at celebrity funerals, says Laderman, who traces today's cult of the famous back to Rudolph Valentino's 1926 funeral. The crowds, Laderman says, were in a collective hysteria one usually associates with religious states.

Much the same happened seven decades later, when three million mourners took to the streets of London to pay their respects to Princess Diana. They lined the entire funeral procession and left more than a million bouquets of flowers at Kensington Palace.

If saints have shrines, so do celebrities, including countless virtual memorials, churches and cathedrals built on the Web. Pilgrims today don't just visit Lourdes or Mecca, they converge in droves at Elvis' Graceland and Michael Jackson's Neverland Ranch.

There seem to be countless similarities, says Bregman, but she warns against making a facile equation between celebrities and saints.

"The value of saints," she says, "was first and foremost their devotion to God and their lives as moral exemplars."

Can Kim Kardashian or Paris Hilton be counted as moral teachers? she asks.

Will our children's children go to Sunday school to learn about the many sacrifices Lindsay Lohan made in the name of her art, including drug addiction and jail?

Scary or not, celebrities do teach us patterns of behavior, says anthropologist Helen Fischer of Rutgers University in New Brunswick, if only because of their ubiquity in print, visual and aural media. It's impossible to get away from them.

Fischer says critics assume that we mimic behavior we see in the media, while, in fact, we develop our morality not just by imitating certain celebrities but by condemning others.

"We use our celebrities . . . as the bouncing off point for our discussion with each other of whom we should emulate and whom we should despise," says Fischer, author of Why We Love: The Nature and Chemistry of Romantic Love (Holt Paperbacks, 2004). "And as we adore them or despise them, you and I are . . . establishing our rules of conduct."

Parents who prize chastity and abstinence from drugs may not want Marilyn Monroe as a moral guide, but traditional values do inhere in a few (saintly?) celebs, most notably Princess Diana, says Linda Woodhead, coeditor of Diana: The Making of a Media Saint (I.B. Tauris, 1999).

"Diana stood for a cluster of values that some people loved - tender loving kindness, looking out for the underdog and the stigmatized person," she says.

Woodhead says devotees have even begun to ascribe miraculous powers to Diana.

"The cult of objects around Diana includes a bust of her on display at a maternity ward in Liverpool," says Woodhead. "It looks just like traditional representations of the Virgin Mary, and people leave her offerings."

Just as women throughout the centuries have solicited Mary's help, says Woodhead, expectant mothers "are making petitions to [Diana] as a mother who shared their concerns."

It does seem, after all, that at least one celebrity has been sanctified - not by any ecclesiastical institution, but by a growing contingent of ordinary people.