Tippin Inn and other relics of an era gone

A big sign off Route 73 in Winslow Township once directed music lovers into what seemed like just a wooded area with a few houses. But several blocks back, there was a seminal source of entertainment for mid-20th century African Americans, who often were excluded from mainstream events.

A big sign off Route 73 in Winslow Township once directed music lovers into what seemed like just a wooded area with a few houses. But several blocks back, there was a seminal source of entertainment for mid-20th century African Americans, who often were excluded from mainstream events.

"Back in those woods was my Daddy's Tippin Inn," said Helen Toomer Beverly, 76. "You turned off 73 and within a block, you could hear the music and smell my mother's fried chicken. Buses would come from Philadelphia and Atlantic City. It was the chicken-and-chitterling circuit, but, boy, there were a lot of people having a good time."

They called that section around Winslow and the tiny town of Chesilhurst and part of Berlin, "East Berlin." It was an enclave where blacks settled during the early part of the last century, like Lawnside near Haddonfield and what was known as Matchtown near the Merchantville/Cherry Hill/Pennsauken border.

The histories of families who lived in those areas will be chronicled Saturday by the West Berlin Historical Association including the story of Beverly's father, James Toomer, who came to the area as a young man in the 1930s.

According to Chesilhurst Mayor Michael Blunt, who grew up in East Berlin, much of the area's population then worked on Depression-era government projects, among the most prominent the building of the White Horse Pike and other roadways between Philadelphia and Atlantic City.

"But it wasn't safe for an African American to go anywhere but by train back to a place like East Berlin or Lawnside," said Blunt, 56. "So the Roosevelt administration promoted places like East Berlin, which were essentially black towns where the workers, who were needed for the projects, felt welcome."

When World War II ended, James Toomer decided to open a club near his home in those woods, so according to Beverly, he got in line at the government office at 4 a.m. the day they gave out the one liquor permit he qualified for as an African American.

"The other guy got there later, so Daddy got it," Beverly recalled.

Beverly's daughter, Judy Hill, remembers that as the club's opening night approached, the family didn't have a name for it, but they expected a lot of people. James Toomer's wife, Mellernese, who did all the cooking, thought the customers might be a bit tipsy and said, "They will be just Tippin Inn." The name stuck, said Hill, 50, who lives in Hammonton.

By the mid-1940s, his Tippin Inn was the place to come for fun.

Toomer also sponsored a baseball team that toured the semipro Negro League circuit. It often comprised his sons, sons-in-law, nephews and friends.

"On summer weekends, they played in a field across Cushman Avenue from the Tippin Inn and the party moved there," said Shamele Jordan, a third-generation member of the Toomer family, a genealogist by profession and, with her cousin Floyd Riley, the keeper of the family history. "Legend has it that the famous musicians who played at the Tippin Inn would play baseball there with the Tippin Inn team."

Riley, 58, a retired school principal who grew up in East Berlin and now lives in another area of Winslow, has copies of ads proclaiming the shows. They show Fats Domino, B.B. King, Ray Charles, Dinah Washington, Big Maybelle, and other music icons of the 1940s, '50s and '60s - the heyday of the Tippin Inn.

"Ike and Tina Turner would come and they would yell at each other . . . but then get on that stage," Beverly said. "My sisters sometimes were Ikettes, just for the night. They were great singers and really beautiful. Fats Domino once heard a couple of them sing and said to my daddy, 'Why do you need me when you have daughters who can sing like that?' "

Riley said that while some of the famous acts came through before they made it big - Charles, for example, appeared at the inn four times in the mid-1950s - others played it because it was part of that chitterlin' circuit, assuring them a payday in comfortable surroundings.

"B.B. King would come with two or three buses and play for a weekend," Beverly said. "Daddy had an apartment upstairs, where King slept, but the other guys in the band stayed on the buses. Daddy said, 'B.B., I can find a place for you, but those other guys have to fend for themselves.' "

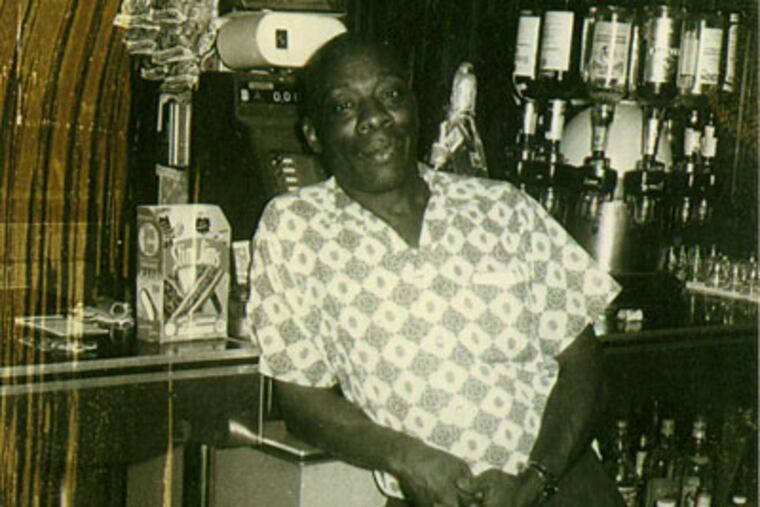

James Toomer died in 1975, but Jordan said the club had already dwindled to mostly a huge bar for 500 people and a restaurant - because performers by then were able to play easily in big cities. His son Gilbert tried to run it, but it burned down accidentally in 1979, a lone house on the corner of Cushman and Cedar.

"I was young when it was going and never actually was allowed in to see a big act, but I remember my aunts and older female cousins, all dressed up, going in there," Riley said. "They were the most beautiful women. That's what I remember about the Tippin Inn. It was a place for beautiful people who otherwise might have been discriminated against to have fun."

If You Go

"Celebrating the African American Community: A Tribute to Family & Culture" will be presented noon to 5 p.m. Saturday by Berlin Township/ East Berlin/ West Berlin Historical Association at Berlin Township Municipal Hall, 135 Route 73 South, West Berlin, N.J. Exhibits will focus on civic associations, places of worship, family histories, education, entertainment, leadership, and influences in the African American community. Information: 856-768-7127, 609-561-5472, or 856-728-8926.

EndText