A psychic with an enemy

Have you ever had a professional enemy? Not a competitor, necessarily (or merely), more like a villain whose hate for you is inexplicable and partly obscured, who sends dirty looks and undermining jabs your way. If so, you know that bad intentions can have a power of their own. In Heidi Julavits' anticipated new novel The Vanishers, which she will discuss Tuesday night at the Free Library of Philadelphia, the bad vibes are so bad, they're supernatural.

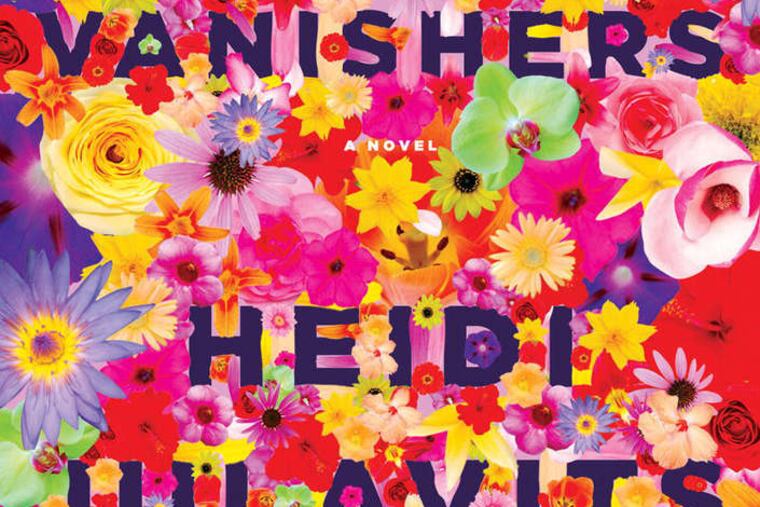

By Heidi Julavits

Doubleday. 284 pp. $26.95

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by Katie Haegele

Have you ever had a professional enemy?

Not a competitor, necessarily (or merely), more like a villain whose hate for you is inexplicable and partly obscured, who sends dirty looks and undermining jabs your way. If so, you know that bad intentions can have a power of their own. In Heidi Julavits' anticipated new novel The Vanishers, which she will discuss Tuesday night at the Free Library of Philadelphia, the bad vibes are so bad, they're supernatural.

Julia Severn is a twentysomething psychic enrolled in the Institute for Integrated Parapsychology, a prestigious workshop tucked away in the White Mountains where astral travelers hone their skills. Her mentor is the formidable Madame Ackerman, a comically self-absorbed "genius" with whom everyone at the Workshop, as it's called, is a bit in love - and who bears more than a passing resemblance to Julia's mother, who committed suicide when her daughter was one month old.

Ackerman employs Julia as her stenographer, responsible for writing down every word she utters as she regresses across space and time. The older woman is currently on assignment, hired to "visit" an office in Paris during the 1980s to locate a film reel made by Dominique Varga, a feminist performance artist and filmmaker known, slyly, as "the Leni Riefenstahl of France."

Julia soon discovers that her mentor is blocked, unable to do anything in these sessions but fall sound asleep. It's Julia who makes the regression, surprising even herself with the extent of her psychic abilities, and when Madame discovers that she's about to be eclipsed by a young rival, she launches an "attack" that devastates Julia with illness. The student is forced to drop out of the workshop and spend her time visiting doctors and getting drugs that not only don't make her better, but also deaden her psychic sense.

But before any of this happens, Julavits writes - in a short prologue so incisive and relevant it will seem to have been written for you alone - about the idea of psychic attack. She makes it seem a totally plausible, everyday occurrence, with unexplained physical ailments as the chief symptoms: a rash, acid reflux, bleeding gums. ("In the beginning, an attack can look just like real life," she practically whispers, giving us the chills.) This few-page teaser might be the strongest part of the novel, actually, or at least the most pleasing - this and the final section with its moving, satisfying moment at the very end. It's what's in the middle that can be harder to negotiate.

While she's convalescing, Julia gets back in the psychic game, hired by the same people who hired Madame Ackerman to try to find Varga. As she bounces around the world, from New York to a psychic healing center in Vienna to another one in Breganz-Belken, she ends up searching not only for the artist but also for a cure, for her attacker, and maybe for her mother, too. Julavits pulls one rabbit after another out of her metaphysical hat, introducing the dead to the living and confounding Julia, and us, with identities that shift and eventually dovetail, like an old-fashioned mystery story.

So what kind of novel is this? It's a satire, to an extent, and a pretty effective one; the workshop looks a lot like an academic enclave, that hothouse environment where pettiness and ambition flourish to a comical degree. Julavits also sends up the "healthcare industry," with thrilling, subversive insights about wellness and illness and the faulty assumptions we can make about both. We learn that the medications that were supposed to make Julia healthy again killed off "the best part of [her]," whereas her supernatural ability - a kind of affliction in itself, something she didn't choose and can't always control - made her feel "fiery" and "alive."

The novel is powerful in many ways. The language is scattershot with jokes - archly amusing, absurd, and ironically elitist humor reminiscent of one of those spoof pieces in the New Yorker: "I could sense their knowing most forcefully in the lobby, a space unwisely constructed of palissandro bluette marble, a stone touted for its properties of thought amplification." Just as often, her characters produce Confucian-style bits of wisdom. "The past is not past if it is always present" goes one such pithy remark. (And ain't that the truth.) On the subject of loss in particular, Julavits is an expert, writing with eloquence and poetry about Julia's confusing grief over a mother she never had. "It was like missing a missing," the young woman explains, and " . . . it scrambled my emotional compass, this magnetic craving toward norths that didn't exist."

Yet the novel's sturdy intellectualism, or maybe something else, keeps us at a slight but constant and frustrating remove. There's heady stuff here - about feminism, about mothers and daughters, and ultimately about life and death - but channeled as it is through Julia's chilly perception of it, interpreting it comes at a cost: The emotional content of much of the novel is confoundingly empty. We learn about the suffering of these folks we're reading about - in fact, that's the only thing the book is about - yet we don't really feel it.

Interestingly, Julavits' story eventually opens up to this fact, seeming to allude to a certain blankness in her main character. "If there's one person you're less interested in than me, it's you," an acquaintance (Julia has no friends) tells her bitterly. A few minutes later, Julia asks an attending doctor if she has a pulse and he answers, "I'm not sure." Maybe this deadness is intentional; to be a conduit for past experiences and other lives, you might need to be little more than a vessel.

Regardless, if you tough it out to the end, you'll get your reward. In bringing Julia to a place of triumph and healing, Julavits achieves a deepening of the novel's wisdom and insight and, finally, delivers a thunderclap of real feeling.