Pastoral paradise on the Parkway

Paul Cézanne's work is not unknown territory to Joseph J. Rishel, senior curator of pre-20th-century European painting at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.Over the years, Rishel has curated five major exhibitions focused on the Post-Impressionist master, as well as numerous others in which Cézanne's carefully constructed canvases have played a significant role. Cézanne is inexhaustible, and a few years ago, Rishel found himself wondering about the possibility of pairing the museum's own The Large Bathers (1900-06) with Henri Matisse's Bathers by a River (1909-17), in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. And what if those two monumental paintings were to be shown in relation to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts' Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897-98) by Paul Gauguin?

Paul Cézanne's work is not unknown territory to Joseph J. Rishel, senior curator of pre-20th-century European painting at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Over the years, Rishel has curated five major exhibitions focused on the Post-Impressionist master, as well as numerous others in which Cézanne's carefully constructed canvases have played a significant role.

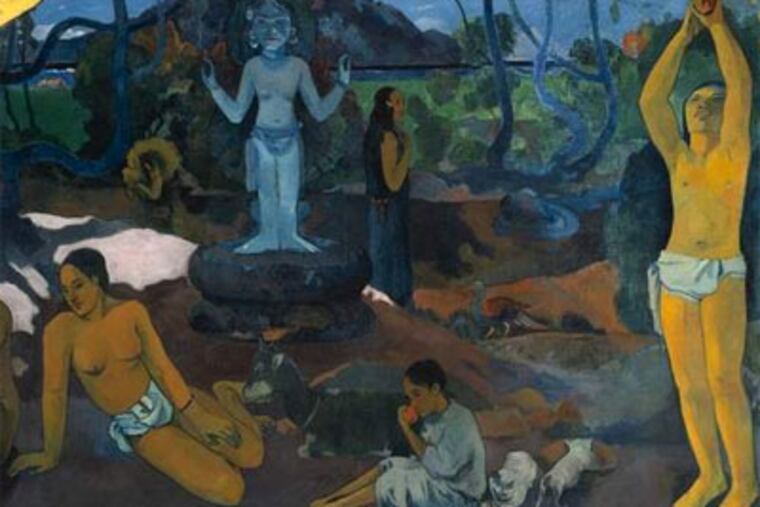

Cézanne is inexhaustible, and a few years ago, Rishel found himself wondering about the possibility of pairing the museum's own The Large Bathers (1900-06) with Henri Matisse's Bathers by a River (1909-17), in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. And what if those two monumental paintings were to be shown in relation to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts' Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897-98) by Paul Gauguin?

The result of this curatorial dream — "Gauguin, Cézanne, Matisse: Visions of Arcadia," curated by Rishel — opens at the museum Wednesday for a run through Sept. 3. The exhibition, which will not travel, is a jewel of a show tracing the persistence of a pastoral ideal from Poussin (the show includes his 1627 The Grande Bacchanale, borrowed from the Louvre) through a great flowering of Arcadian imagery in the years immediately preceding World War I.

Here we find Rousseau's The Dream (1910), Derain's Bathers (1907), Picasso's Adolescents (1906), Delaunay's City of Paris (1910-12), and works by Kirchner, Marc, and others. All examine the notion of a lost land of peace and harmony, a landscape of erotic innocence — a notion dating back to classical Greece and Rome.

Why is it, Rishel wondered at Friday's media preview, that "when the going got really tough," painters such as Gauguin, Matisse, Picasso, Delaunay and others — "the most radical and advanced people" — looked about and "reverted to the oldest … themes?" What drew them to "people standing around without clothes on under the trees?"

Of course, part of it is certainly the fact of people "standing around without clothes" supposedly bathing, although Rishel points out he has never seen "any cake of soap" in all the many images of woodland bathers.

But perhaps, given the importance of the Arcadian theme at the turn of the 20th century and in the years around the war, the power of the ideal of utopia is of equal and even greater importance, he said.

"Better times are coming" is a thought behind virtually all Arcadian thinking, Rishel says.

In art historical terms, the canvas by Poussin is the wellspring for this exhibition, he said — "the template" for all that came after. Cézanne said he wanted to "remake Poussin after nature" and in The Large Bathers, he succeeded.

In developing the idea for "Visions of Arcadia," museum director Timothy Rub encouraged Rishel to think expansively. And so "Visions" explores Cubism and German Expressionism, painting and sculpture and drawing.

Arcadia, noted Rishel, is not simply an idea and ideal, it is also an actual place in Greece. He and his late wife, Anne d'Harnoncourt, former director of the museum, were driving in the Greek mountains years ago, he recalled, with d'Harnoncourt scrutinizing maps.

"Do you know where we are?" she asked him.

"Of course I do," Rishel replied, eyes on the road ahead.

"We're in Arcadia," she said.