Legendary studio engineer Ken Scott on working with Beatles, Bowie

EVEN 50 YEARS ON, Ken Scott can't really deal with the notion that the music he helped to create has affected millions of lives, has truly changed the world.

EVEN 50 YEARS ON, Ken Scott can't really deal with the notion that the music he helped to create has affected millions of lives, has truly changed the world.

Nor can he fathom that many of those life-altered listeners would be curious enough to come hear the legendary record producer/engineer lecture (as Scott's doing Tuesday evening at Drexel University) or read his newly published memoir, Abbey Road to Ziggy Stardust (Alfred Music Publishing, $24.99), written with a little help from Bobby Owsinski.

"Back then, we never had the notion this stuff would last," says the 65-year-old Scott, who was the recording-studio helmsman for such talents as the Beatles, David Bowie, Elton John, Pink Floyd, Lou Reed, Jeff Beck, Supertramp, Duran Duran and Philly fusion-master Stanley Clarke.

"Rock was still young back then," Scott said, and so was he. He quit school, got his first gig at London's prestigeous EMI Studios (later renamed Abbey Road Studios, after the location-checking hit album) when he was all of 16.

"I wrote a letter asking for a job and miracle on miracles, they responded and made me a studio librarian - collecting, organizing and filing the recordings. I thought I was the luckiest kid in the world."

It was then pretty common for young Brits to leave school "as early as 15," Scott rolls on in our recent chat. But few contemporaries had a grasp of their future as focused as his. Scott had enjoyed early exposure to a Grundig magnetic tape recorder and microphones, and became obsessed by the technology of capturing and manipulating sound.

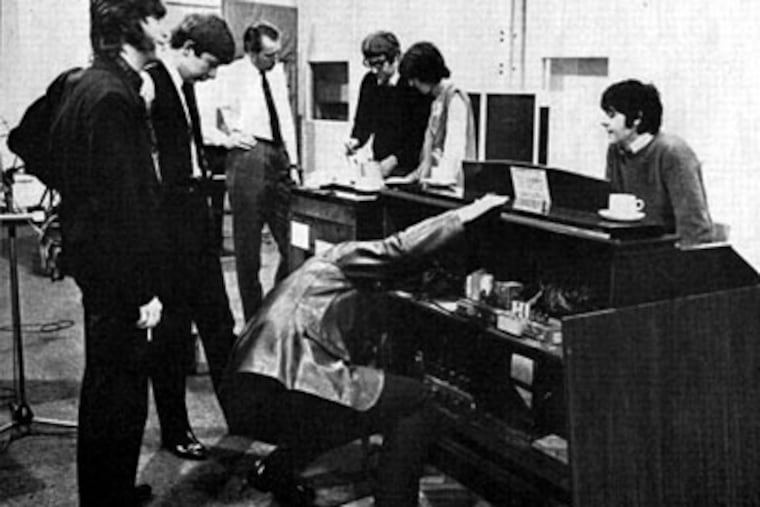

Awestruck to be working in the same building as the World Biggest Band, Scott sometimes dared to sneak into a studio and snap a few photos of the Fab Four during sessions - under the pretense of gathering tapes. But even after he'd been elevated to assistant engineer (to Geoff Emerick) and then chief engineer for recordings of the Beatles' "Magical Mystery Tour" and the double disc "The Beatles" (a/k/a the "White Album"), Scott never dared take notes about what was going on, beyond the required notations marked on tape boxes.

So how did he clear away the cobwebs and put his recent book together?

One thing that helped is that Scott's brain had never been clouded by drugs. So that semi-comical adage, "If you can remember the '60s you weren't really there," doesn't apply here.

The Beatles "would sometimes adjourn a recording session for a 'group meeting' upstairs, but I never went along," Scott recounted. "Even later, when I was working with David Bowie and Lou Reed and there were drugs everywhere," he said, "I didn't partake. Music has always been my drug of choice. And I was already crazy enough without needing any help."

For the sake of accuracy, though, Scott sought out story confirmations from others, like Beatles' producer George Martin and Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page. And the author visited a hypnotist to engage in regression therapy.

"Still there were things no one could reconstruct, like the day Eric Clapton came in to record on 'While My Guitar Gently Weeps,' " Scott shares with a laugh. "It's one of those 'What was that like?' situations people always ask me about, because Eric's solo is so memorable and it was rare that the Beatles would have an outsider participate. Yet I don't remember it at all!"

But there are plenty of anecdotes and insights to garner from the book, as the man explains the process of recording (with lots on miking secrets), debunks myths (Yoko didn't "break up" the Beatles; "Ziggy Stardust" wasn't really a concept album) and bemoans how "they don't make 'em like they used to."

In the early album-rock era, he explained, the creative process was all about spontaneity and having fun and working under pressure - putting out a new long player every six months or a single in as little as a day - as John Lennon did with "The Ballad of John and Yoko," he said. "Today, a label takes six months just to 'set up' a new release," snorts Scott.

"It was never about the money," he adds. "That's a core message I hope young musicians take away. Today, many experts warn about the 'evils' of the music business: 'Don't sign this; don't give away that.' Still you wind up making the same mistakes, often because you have to" to get a deal.

"And that's OK. If you're doing what you love, it doesn't really matter if your music sells or not, if you get the proper credit or royalties. You're doing it for the right purpose."

That all helps explain why Scott "never stopped working with Bowie, even when his manager" - the infamous Tony "Deep Freeze" Defries - "never paid us royalties or even fees to the studio where I was working then. We never got much money out of Bowie until he went public, sold the 'Bowie Bonds.' "

Another consolation is that Defries - like Elvis Presley's greedy manager Col. Tom Parker - royally screwed his talent, too, which Scott shares in chapter and verse. The manager grabbed 50 percent "off the top" (gross income) and contracturally forced Bowie to pay all band/production costs out of his share.

Scott also urges musicians to embrace the moment and the mistakes - a philosophy that artists, producers and record labels rarely grasp in today's high-tech and budget-crunched recording environment.

"We worked in a four-track world, where you had to make snap decisions how to mix and pack a recording, and had to physically splice tape sections together to make edits - a process I really miss," Scott allowed.

"With today's use of Pro Tools and multi-multi-track digital recording, all human flaws are automatically eliminated from vocals. You can record a guitar solo 56 times over and then pull out the 'best parts.' There's no rationale today for keeping an error in. But that's where you'd hear the humanity of the moment," Scott argues. "It's the 'X-factor' missing on too many recordings."

David Bowie, Scott cites, was a "one- or two-take singer. He never wanted to record a song more than that. He wasn't a perfect singer. He could go off-pitch or mess up the timing. But he kept it real. I remember him crying at the end of a vocal on 'Five Years' because he was so emotionally connected to the song."

Many's the time in Scott's early career at EMI when he thought he was about to be fired for doing the wrong thing: accidentally erasing a bit of a track or allowing a vocal to distort, only to have the Beatles decide "let's just go with that."

Clearly, the group knew how to take lemons and make lemonade - turning an accidental erasure of snare drums on "Glass Onion" into a theatrical surprise and not caring a whit that an inserted vocal fix on "Yer Blues" sounded tonally different from the earlier recorded part. "John suggested 'Let's not fake it. Let's make it really obvious - exaggerate the difference.' "

Tellingly, Scott gives short shrift in his tome to project co-producers who were too perfection-minded. He finds nothing good to say about Philly guy Todd Rundgren for totally commandeering the mixing sessions for The Band's "Stage Fright" album. He also dismisses a "high-strung" Phil Spector for the laying on of too much gloss on George Harrison's classic "All Things Must Pass."

"There was talk of reissuing 'All Things' without the Spectorized strings - as had been done with the early Glyn Johns mix of the Beatles' "Let It Be," says Scott. But then George Harrison (the quartet member who remained closest to Scott) died. "That music was so important to him. It's never seemed right to do a remix without his input."

Ken Scott talks and signs books at Drexel's Westphal College of Media Arts and Design, Stein Auditorium (Nesbitt Hall, 111), 33rd and Market treets., 6 to 7:50 p.m. Tuesday, free, 215-895-1029.