A grunt's-eye view of the football industrial complex

Unless you're a hard-core Denver Broncos fan, it's unlikely you remember Nate Jackson. In six NFL seasons playing wide receiver and tight end before his career came to a close after the 2008 season, Jackson caught a total of 27 passes for two touchdowns. If you ever made the mistake of adding him to your fantasy roster, you probably dropped him after one week.

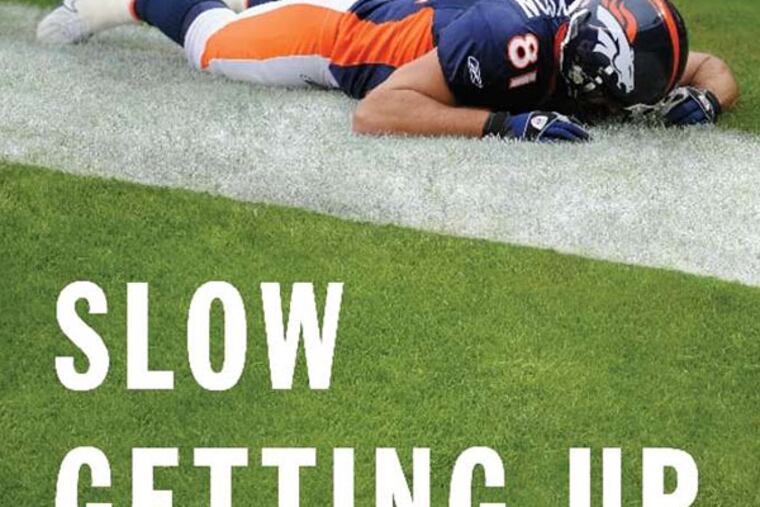

Slow Getting Up

A Story of NFL Survival From the Bottom of the Pile

By Nate Jackson

Harper Collins. 256 pp. $26.99

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by Dan DeLuca

Unless you're a hard-core Denver Broncos fan, it's unlikely you remember Nate Jackson.

In six NFL seasons playing wide receiver and tight end before his career came to a close after the 2008 season, Jackson caught a total of 27 passes for two touchdowns. If you ever made the mistake of adding him to your fantasy roster, you probably dropped him after one week.

There's little that's out of the ordinary about Jackson's career - other than it lasted twice as long as that of the average NFL player.

But he does have one atypical talent that sets him apart from his helmeted brethren: He can write.

Slow Getting Up is a terrific memoir about a brutally violent sport that ravages its protagonists' bodies. It's foul and funny and keenly observant, and wholly delivers on its promise of sharing a grunt's-eye view of what life is like on the ground floor of the football industrial complex.

Along with A False Spring, Pat Jordan's 1975 heartbreaker about a pitching phenom's major league hopes being spoiled by injury, it's the best non-superstar pro sports memoir I've read.

Here's Jackson, for instance, on the challenges of being a marijuana smoker while playing professional football: "NFL stonerdom is a more calculated endeavor. The offseason months, which might be used to make ganja-induced epiphanical deposits in the bank of the soul, instead are spent abstaining in anticipation of the league's once-a-year drug test."

An all-American at Division III Menlo College, a California school with ties to the San Francisco 49ers, Jackson's NFL odyssey begins with a tryout with the Niners, who trade him to Denver.

In Colorado, Jackson sticks. He makes the practice squad, then is shipped off to Düsseldorf, Germany, to play for the Rhein Fire in the NFL development league. Eventually, he makes the Broncos' 53-man roster, plays special teams, and earns a starting spot at tight end.

Along the way, he separates his shoulder several times, pops hamstrings, tears up his knee, mangles a pinkie finger, shreds the muscles in his groin, and breaks his tibia. A typical day at practice, spent getting jammed at the line of scrimmage by cornerback Champ Bailey, goes like this: "My body feels fine. My knee's healed. . . . The only thing bothering me, except for the typical early training camp agony are the terrible blisters that Champ's indirectly causing to bubble on my feet.

. . . After the first day of camp, my feet are hamburger meat."

Jackson's decision to submit to "the needle-as-savior approach to injury treatment" seems perfectly logical. Soon, he knows new vocabulary words: Toradol, Bextra, Kenalog, dexamethasone. After the Broncos cut him and he's desperate to get back with an NFL team, he starts using human growth hormone.

But does all the pain make Jackson hate his job?

Hardly. He loves it. In part, that's because of the spoils, even for a no-name NFL grunt who never strikes it all that rich. (He does sign one contract that includes a $485,000 signing bonus.)

Jackson is a returning hero who never needs to buy a drink in his hometown, a "meaty unicorn" celebrated everywhere in Bronco nation, who gets to ride around with Broncos cheerleaders at team golf tournaments. His "mancation" adventures with buddies in Vegas amusingly end up in a gutter of booze, sex, and self-loathing, and he paints a hilarious, icky image of a team full of masturbating football players alone in their hotel rooms the night before a game.

Denver head coach Mike Shanahan (now with the Washington Redskins) comes off well, a class act who treats his players like men. Less appealing is Eric Mangini, the coach in Cleveland when Jackson - who also has failed tryouts with the Eagles and New Orleans Saints - briefly lands a job with the Browns. Mangini is portrayed as an insecure martinet more intent on demonstrating his authority than teaching his players to win.

So what makes it all worth it? Here's Jackson's description of taking the field for a season opening kickoff: "The electricity runs through the fans and through the grass and up through my feet, bringing me into a zone where I feel neither fear nor worry . . . . I can feel the energy reaching towards a crescendo, towards the moment when the ball pops off the foot of the kicker and towns and cities and dreams full of football energy finally explode into the kinetic, into the now . . . . There is no feeling that will ever replace that moment in my life. I know that now."

@delucadan