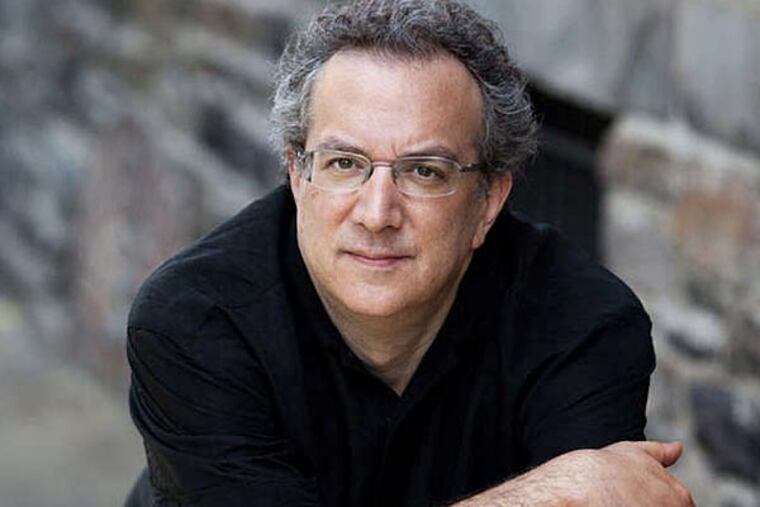

Composer Uri Caine finding new Philadelphia roots

Jazz pianist/composer Uri Caine's many years gone from his native Philadelphia are melting away, into a kind of music he wasn't taught at the University of Pennsylvania, and in places his colleagues don't typically navigate.

Jazz pianist/composer Uri Caine's many years gone from his native Philadelphia are melting away, into a kind of music he wasn't taught at the University of Pennsylvania, and in places his colleagues don't typically navigate.

His The Passion of Octavius Catto, a jazz/gospel oratorio about the martyred Philadelphia civil rights leader, will have its world premiere Saturday at the Mann Center for the Performing Arts. It is being rehearsed at the historic St. Paul's Evangelical Lutheran Church in what's called in hip-hop circles "the O-Zone" (Olney), with a chorus that chants his name when he arrives. "U-ri Caine! U-ri Caine!"

Such colloquial familiarity isn't likely to be found in the modern-music festivals of Europe that Caine has been sandwiching between local rehearsals. No wonder he pops down from New York whenever possible - 15 rehearsals so far - to accompany and sing with the Freedom Festival Community Choir, made up of area church singers and professionals.

"It's good to do that. It's the communal aspect of making music," he says. "Whether somebody is from Poland or Cuba . . . we come together and play and talk about differences and nuances. You tell me what you're about . . . and it really becomes richer."

That's the ultimate point of the Mann Center's months-long Philadelphia Freedom Festival, climaxed by the free, fully subscribed Gospel Meets Symphony concert Saturday with the Philadelphia Orchestra at the Mann. The headliner may be gospel singer Marvin Sapp, but Caine's piece, commissioned by the Mann, dominates the first half.

The Civil War-era Catto (1839-71) is the central figure, spurred by Tasting Freedom: Octavius Catto and the Battle for Equality in Civil War America (2010) by Inquirer editor Daniel Biddle and his retired colleague Murray Dubin. The book, in fact, was what pushed Caine to take the commission. "The book talks about places I really know here," he says. "The racial story here . . . is such a deep thing."

The piece touches on such key events as the 1838 burning of Pennsylvania Hall, built for abolitionist meetings and destroyed days after it was finished. It quotes from Catto's speeches about racial equality, and deals with the era's forced integration of streetcars. "You can't ride, you can't ride" sings the chorus emphatically, "in Phil-a-del-phia."

Caine, 58, might seem unlikely for a piece that might logically have fallen to an African American composer. The composer himself expressed surprise, saying, "I have no idea how people find me."

Freedom Festival Community Choir director Jay Fluellen says he championed Caine, partly because of his jazz roots but also because he reaches so far beyond that. "It's the exact right blend of elements to express and spread the story," he said. "Music doesn't fall into black and white."

During the playful but disciplined rehearsals, singers detect undercurrents that Caine didn't realize were there, such as influences from the protest gospel music of the 1970s exemplified by the Edwin Hawkins Singers.

"It's in my DNA," Caine says. "I'm not trying to be something I'm not."

In fact, he grew up on something close to the front lines of Philadelphia racial struggles: His father, Burton Caine, now a Temple law professor, headed the American Civil Liberties Union during the turbulent '70s. Telephones were tapped. The elder Caine had an FBI file.

"We were always involved in that kind of politics," Uri Caine said.

He remains politically alert, seeing parallels between Catto, who was shot to death on Election Day 1871 en route to a polling place, and last year's Supreme Court decision invalidating a key part of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. He sounds almost apologetic for not following in his father's footsteps.

But the one piece of advice father gave son was to stay away from the law. "I spent 25 years at it, and it was very, very intense," said the elder Caine. "Our instruction to our children was to follow your heart."

So Caine went on to create a curious niche: A jazz musician unafraid to improvise on classical composers from Haydn to Mahler - in 2009 he was nominated for a classical-crossover Grammy - he is seen in some European circles as part of a trend to build new works atop old ones.

In one of his bolder re-imaginations, the folksier moments of Mahler's Symphony No. 1 are transplanted into woozy, earthy klezmer realms. His remake of Schumann's song cycle Dichterliebe used new poems by his mother, Shulamith Wechter Caine.

Sometimes called avant-garde, Caine can be as intricate and modernistic as anybody, or downright giddy, as in Fern Hill, his British-accented work for England's Halle Orchestra.

His common denominator is simple: While most composers imagine the piece first and then think about performers, the performers are his starting point. "Once I know who will be playing and what the sound of the music will be . . . I can begin to create the music," he says. "Then, form and style reveal itself."

Another characteristic is density: Caine always seems to have much to say in little time, so cooperative spirit isn't just a courtesy but necessary to keep the music performable. "Some of the stuff I wrote [for Catto] was difficult, and I said I'd be happy to simplify. But they stuck with it, and now it sounds good."

The chorus even sways to his music. As focused and down-to-business as Caine can be, he says, "I like that!"