New Franklin Institute exhibitions reveal how much animals and humans are alike

To prepare their newest project, Body Worlds: Animal Inside Out, German anatomists Gunther von Hagens and Angelina Whalley needed a forklift.

To prepare their newest project, Body Worlds: Animal Inside Out, German anatomists Gunther von Hagens and Angelina Whalley needed a forklift.

Von Hagens is famous for the 1977 invention of plastination, a preservation technique that allows the anatomy of once-living beings to be displayed indefinitely. He and Whalley needed heavy machinery to maneuver the body of a full-grown giraffe into various substances that would dehydrate and then plasticize its tissues and organs. The process took more than two years.

The giraffe's muscles are fused into their natural formation, an immobilized representation of the powerful sub-Saharan animal unsheathed from its patchwork-spotted hide. Along with more than 100 other animal plastinates, the tallest land animal stands at its full height in the Body Worlds exhibit, which opens at the Franklin Institute on Saturday. Philadelphia is the fourth U.S. city to host the exhibit, after Chicago, Dallas, and Salt Lake City.

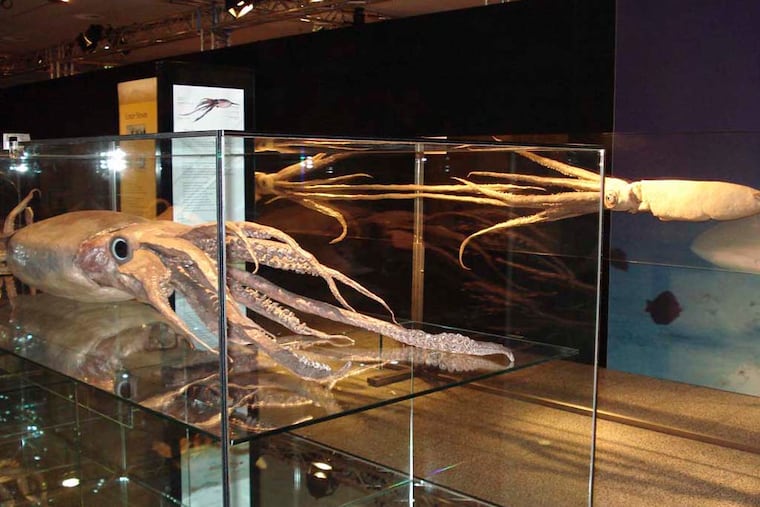

Full animal specimens, including a giant squid, bull, ostrich, camel, and reindeer, will appear alongside cross-sections of body parts and preserved internal organs of all kinds. Body Worlds: Animal Inside Out runs concurrently with Sesame Street Presents: The Body, an interactive exhibit designed for young children that opened last Saturday. Frederic Bertley, senior vice president of science at the Franklin Institute, said that although both exhibits were intended for families of all age ranges, Body Worlds itself was appropriate for children. The Sesame Street exhibit provides learning activities that allow young visitors to touch and play with various displays about organs, from the nose to the digestive system.

Larry Dubinski, who became president of the Franklin Institute in July, agreed Body Worlds appeals to visitors of any age and recalled that whenn the exhibit came to the science museum for the first time in 2006, with human bodies, he took his two children, who were then 6 and 4. Body Worlds returned in 2009 with another human exhibit.

His children gained an "experience that they remember today and will remember for the rest of their lives," Dubinski said.

"There is not a person alive who looks at a Body Worlds specimen and doesn't remember that for the rest of their life," Bertley said. "It's really compelling because it's so different."

Bertley said he was particularly excited about Body Worlds: Animal Inside Out because bringing excitement and interactivity to science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) education is of the utmost importance. The plasticized bodies can do that for everyone, especially elementary and middle school children, he said.

"Kids are born curious," Bertley said. "But our educational system, unfortunately our public educational system, doesn't reward the curiosity. School gets boring - especially the sciences are really boring and complex and hard." The STEM educational potential of Body Worlds is immense, he said.

Previously, Body Worlds exhibits were focused on human anatomy, with just a few animal specimens included in special displays - notably a horse with riders. This time, only a few human specimens, including a full plastinate body and full skeleton, will be on display. Dubinski said evaluations of exhibits had shown visitors wanted to know more about the animal world; this exhibit "gives people what they want," he said.

"One of the coolest things about this exhibit is that once you strip off all the fur of the animal and you look at these plastinated specimens, you realize, 'Wow, as much as there are a lot of differences between animals and, of course, there are differences between humans and animals, there's also a lot of similarities,' " Bertley said, naming the digestive, nervous, and reproductive systems as strikingly similar.

Angelina Whalley, creative and conceptual designer of Body Worlds, said the idea of human and animal similarities was something she and von Hagens wanted to emphasize by creating Body Worlds: Animal Inside Out. She said the human exhibits drew crowds because "most people are curious to find out what they are made of." She hopes animals will present an equal draw, to promote greater compassion for endangered and threatened species in particular. She will be present for Saturday's opening of the Franklin Institute exhibit.

Though the consent process for obtaining human specimens might seem more complicated, producing the animal exhibits was still a challenge, Whalley said. Unlike humans, animals can't volunteer to have their bodies displayed after death. Body Worlds receives donations of animals that have died of natural causes from institutions such as zoos, game parks, reservations, and veterinary schools, according to its website. However, obtaining animal specimens requires a lot of paperwork and cooperation from the institutions. Among those who have disclosed their donor status are the Hanover and Neunkirchen zoos in Germany.

Despite the controversial nature of body donation for display purposes, Bertley said the exhibit encourages proper treatment and respect of animals. Dubinski said there was no controversy for the Franklin Institute, because "if you love animals, you're going to love this exhibit."