E.O. Wilson's 'Half-Earth': A bold proposal to save biodiversity

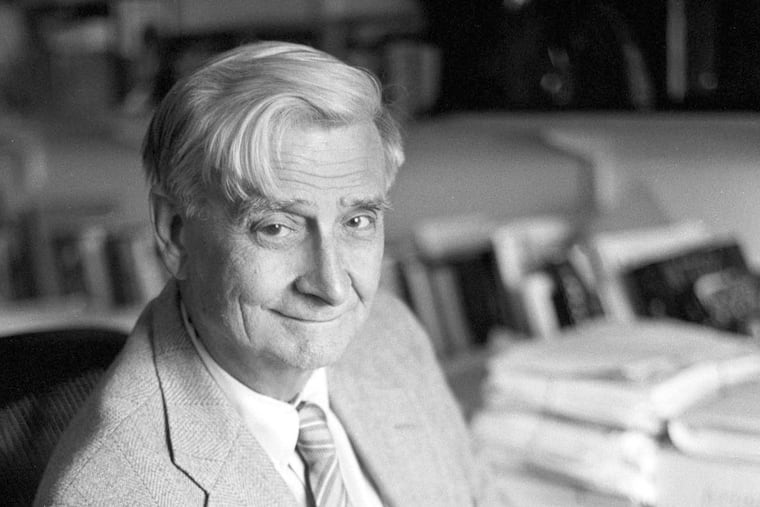

Entomologist Edward O. Wilson, the modern era's Rachel Carson, has an audacious idea that might jump-start a lagging conversation about a burning issue.

Half-Earth

Our Planet's Fight for Life

nolead begins By E.O. Wilson

Liveright. 272 pp. $25.95 nolead ends

nolead begins

Reviewed by Mike Weilbacher

nolead ends Entomologist Edward O. Wilson, the modern era's Rachel Carson, has an audacious idea that might jump-start a lagging conversation about a burning issue.

"I propose," he writes in Half-Earth: Our Planet's Fight for Life, "that only by committing half of the planet's surface to nature can we hope to save the immensity of life-forms that compose it."

That's right: Half-Earth asks us to set aside half the world for the rest of creation.

The leading spokesman for what is now called biodiversity, Wilson worries we are on a path to losing at least half the planet's species. The ark of life is sinking from a long list of insults: climate change, habitat loss and deforestation, invasive species, pollution, poaching, overfishing.

As though that's not tragic enough, deep into the 21st century, we are still clueless as to how many species share this ark. Though we've named some two million species, from amoebas to zebras, Wilson estimates there may be eight, even 10 million species total, which means we are losing uncountable species we've never even met.

Extinction is a natural phenomenon, as the Academy of Natural Science's fossils remind us. But what is happening today is decidedly not, and Wilson carefully lays out the research indicating we have raised the extinction rate to 1,000 times the natural background rate "and accelerating."

He calls biodiversity loss "one of the great moral questions of all time," and he's right. If we accomplish his grand Half-Earth vision, models indicate we preserve 80 percent of that biodiversity. We lose one to two million species, but the ark stays afloat.

Wilson knows controversy, having set off a firestorm in the 1970s with his groundbreaking Sociobiology. Here, he takes on "de-extinction enthusiasts, nature-is-dead defeatists, and sundry ideological anthropocentrists." Living in a world where the Amazon is no longer a river but a retail website and clouds store data and not rain, he confronts "Silicon Valley dreamers of a digitized humanity" who "have failed to give much thought . . . to the biosphere."

Wilson invokes multiple biblical references. He includes a lengthy quote of the passage in which God taunts Job, a startling section of the Bible that a rabbi friend described to me as one of the oldest pieces of extant nature writing. Unlike most science writers, he's plowed this field before: Ten years ago, he wrote a book addressed to clergy, pointedly questioning their absence in the fight to save creation.

Half-Earth is at its best when it describes some of the extraordinary creatures at the center of the biodiversity battle, such as the unfolding misfortune of the rhinoceros, a charismatic creature vanishing because its horn is thought by some to increase our sexual prowess. The book dives into the ocean to describe Picozoa, a submicroscopic new phylum named only in 2013. He tells of how the loss of the chestnut tree caused the quick collapse of the passenger pigeon.

Wilson risks losing readers - as he lost me - when he goes into long digressions late in the book on the working of the human brain. And some of the chapters read a little thin. But fine: If he can get the world's attention on this issue, breaking through the cultural clutter and background noise of Kardashians and bachelorettes, Brangelina and Trumpism, he'll have accomplished something huge.

"The only hope for the species still living," he concludes, "is a human effort commensurate with the magnitude of the problem." To date, effort pales in comparison to magnitude, and if Half-Earth takes us any closer to sparking greater effort, it will cement Wilson's already remarkable legacy.

Mike Weilbacher (@SCEEMike, or mike@schuylkillcenter.org) directs the Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education in Upper Roxborough.