'String Theory': Transcendant tennis book serves an ace

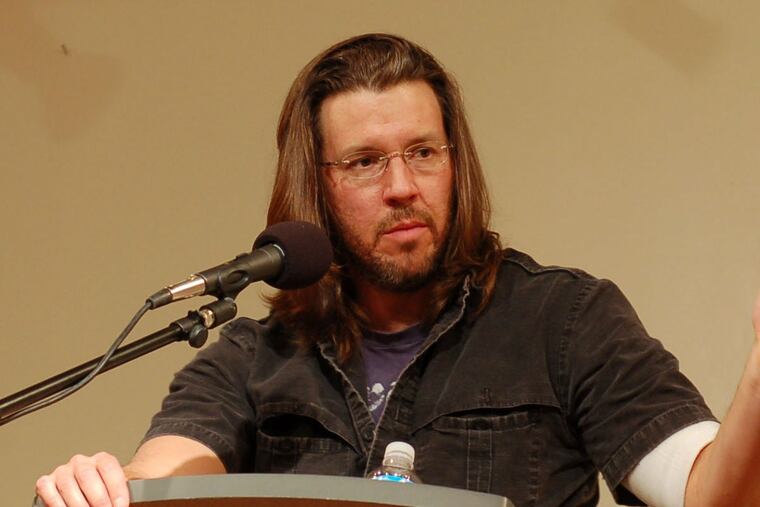

I have a theory. This theory, I suggest, explains the quality of David Foster Wallace's tennis writing, collected in String Theory - its savvy, if not its scintillation, though knowingness may be father to dazzle. My theory is this: anxiety sweat.

String Theory

David Foster Wallace

on Tennis

Introduction by John Jeremiah Sullivan

Library of America.

144 pp. $19.95

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by Peter Lewis

nolead ends I have a theory. This theory, I suggest, explains the quality of David Foster Wallace's tennis writing, collected in String Theory - its savvy, if not its scintillation, though knowingness may be father to dazzle. My theory is this: anxiety sweat.

In high school, Wallace sweated excessively, which, however cooling, is not cool. American boys have been taught not to let 'em see us sweat, and a cold sweat is the height of shame - the sweat of panic. (Starting his Kenyon commencement address, Wallace issued a preemptive strike: "If anybody feels like perspiring, I'd advise you to go ahead, because I'm sure going to.")

For a sport in high school, Wallace chose tennis. In the wet-mitten humidity of Wallace's Midwest, if you didn't sweat on the court, you were considered weird. He could walk around school with his racquet and towel. "Just in from the court," dab, dab. Game, set, match.

But a curious thing happened on the court: Wallace took to tennis. He played the sport as a head game. Competitive tennis "requires geometric thinking, the ability to calculate not merely your own angles, but the angles of response to your angles."

His appetite for math was further fed by the Midwest's incessant wind, which he would figure into his calculations. His was the waiting game that Martin Amis describes as "craven retrieval." Wallace would send back "moonballs baroque with spin" until his adversary went hysterical, hit for a winner, and the wind blew it out.

Move up a level, and the head game alone won't work. You have to have the package. Wallace was being modest when he wrote he lacked the physical goods. He had talent enough to reach No. 17 in the USTA Western Division. Thus, the savvy: He was a tennis player. He knew the game, he knew what court sense meant - when the brain melts and intuition takes over; you don't make No. 17 without moments in "the zone."

So when he stood courtside watching world-class play, he understood he was witnessing certain physical laws being routinely violated, à la Muhammad Ali and Wayne Gretzky, something of beauty, mystery, and sublimity. Laugh, but it's real.

Wallace brought to tennis writing the complete package: knowledge of the game and a style in a zone of its own, a distinctly ingenious talent for sprawling distillation, detail, whisking highbrow with lowbrow, deploying the vernacular to reach higher ground, and fervidity, free of irony and code.

The five pieces in String Theory - profiles of Roger Federer (driving to Wimbledon, his London cabbie says that watching Federer play was a "bloody near-religious experience") and Michael Joyce, and a smackdown of the autobiography of Tracey Austin (of whom he was a rabid fan). Here he unveiled the secret. What goes through a great player's mind when all is on the line? "Might well be: nothing at all."

Also included is a winsome (sorry, yes) autobiographical essay and a vivisection of the obscene commercialization of professional tennis. These essays are not only informed and artful, but also comic and, at times, confidently poignant, as in writing of "that strange mix of caution and abandon we call courage." This is a found truth, and wonderfully, stylistically raw.

"Tennis is the most beautiful sport there is, and the most demanding": Unfolding this comment, Wallace must square the circle. The highest level of the game is played with narrow intensity and ascetic focus, the mind on automatic. It demands "a consent to live in a world that, like a child's world, is very serious and very small." When tennis transcends, it requires the sacrifice of a holy person.

Peter Lewis is an editor at the American Geographical Society in New York City.