Lost work by cartoon great Will Eisner published by Philly's Locust Moon Press

It isn't every day, as Josh O'Neill put it, that you have an opportunity to publish work that shows something akin to a "teenage Shakespeare becoming Shakespeare."

It isn't every day, as Josh O'Neill put it, that you have an opportunity to publish work that shows something akin to a "teenage Shakespeare becoming Shakespeare."

But that's what O'Neill's Locust Moon Press in West Philadelphia believes it is doing.

This week, Locust Moon officially brings out The Lost Work of Will Eisner, a 70-page compendium of the legendary cartoonist's very early work, much of it never seen before.

For those unfamiliar with Eisner, who died in 2005, legendary is not a word used lightly here.

He transformed the world of comics, first with his famous, moody strip, The Spirit, which ran from 1940 to 1952, then with his book-length A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories (1978), which began the now-torrential wave of graphic novels, and then with Comics and Sequential Art (1985), which helped establish the study of comics and comic strips as a serious intellectual pursuit.

The comic strips in The Lost Work of Will Eisner predate all of that.

They present a teenage Eisner's first public efforts working in the exploding realm of newspaper comics and demonstrate his own dramatic youthful growth as an artist and storyteller.

"This guy would become one of the great geniuses of comics, and you can see him developing his voice," O'Neill said.

And these strips really were lost - some appeared in very obscure small weeklies, some in short-lived compendiums, many never at all - until Joseph Getsinger, a Woodbury Heights comics aficionado and former New Jersey state trooper, had a hunch that some old zinc printing plates were worth acquiring.

About eight years ago, Getsinger, 67, a fine artist as well as a retired arson investigator, hitched up with some friends at an annual poker party and learned one of them had a cache of plates used for printing comics in newspapers.

The friend had bought the plates but wasn't interested in researching them. There were about 5,000. Another man had nearly 4,000 from the same warehouse trove.

"He's talking about these printing plates, and I said, 'Wow, I'd like to see them,' " Getsinger said.

Somehow, these plates had survived the scrap-metal meltdowns of World War Two and the Korean War.

Getsinger bought the lot and began trying to figure out what he had. Some things were obvious - plates of strips by Bob Kane, creator of Batman; plates of strips by Jack Kirby, creator of Captain America.

But there were a slew of plates that seemed vaguely familiar - by an unfamiliar writer and artist.

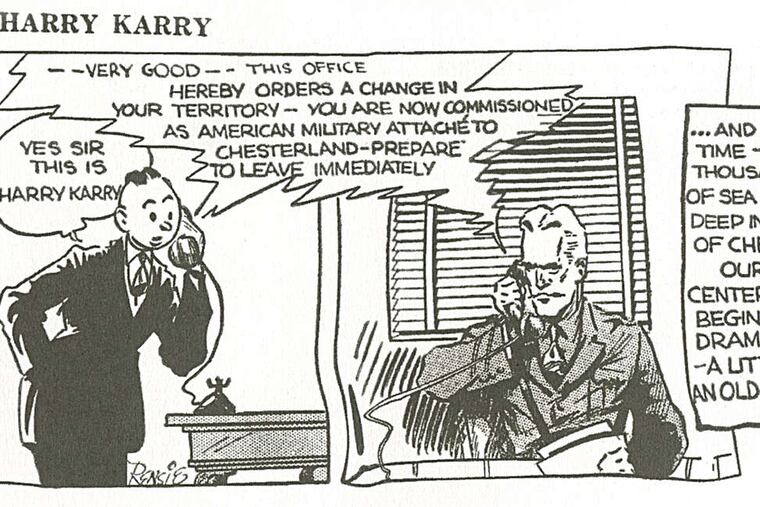

"I came upon these plates of something called Harry Karry by Willis B. Rensie," Getsinger said. "It didn't mean anything, but it was interesting because it was about a detective, and I had spent my career as a detective."

Getsinger employed his professional detective skills and quickly determined Rensie was simply Eisner spelled backward.

The plates were the product of an early joint venture between Eisner and fellow cartoonist Samuel Maxwell "Jerry" Iger. They worked together from 1936 to 1939, churning out strips from their Eisner & Iger Studio in New York.

"There were 104 Will Eisner plates," said O'Neill, 34.

The plates contain material for two youthful strips. The first is Uncle Otto, whose protagonist is a pear-shaped, laconic man with a narrow stovepipe hat and a penchant for slapstick.

Getsinger points out that strip art has roots in the work of Popeye creator E.C. Segar. Denis Kitchen, in his introduction to the Locust Moon volume, notes that Uncle Otto resembles work by Otto Soglow, creator of The Little King.

Eisner worked up Uncle Otto in 1937 using the pen name Carl Heck. It appeared in the oversize Jumbo Comics and then disappeared.

Harry Karry, the second strip in Lost Work, is where the aesthetic and storytelling fireworks can be found. This strip, which Eisner first tried out in his Bronx high school newspaper before returning to it later, began as a kind of jokey, silly take on detective stories.

But something happened, and it happened with a bang.

In the ninth panel, the style radically changes - in the middle of the panel. It begins with jokey Harry in the first part, but the second part focuses on the far more sinister world of intelligence agent ZX-5 in Chesterland.

Harry is gone, never to return. Gone, too, is the stylized drawing of the early Harry panels, replaced by something more realistic and imaginative.

A reader can see the youthful Eisner, then only 21, creating the art and storytelling of The Spirit, which began appearing within a couple of years.

"You can see him become a genius," said O'Neill. "It's very cool. The Spirit is a guy in a suit and mask, and there's a sequence here [in Harry Karry] where secret agent ZX-5 goes to a masquerade ball dressed in a suit and a mask. He almost looks like The Spirit."

215-854-5594

@SPSalisbury