Philly novelist Andrew Ervin takes us on a ride through video game history

If Shakespeare were alive today, he wouldn't waste his time writing plays. Or film scripts, for that matter. No, he'd be a video game designer.

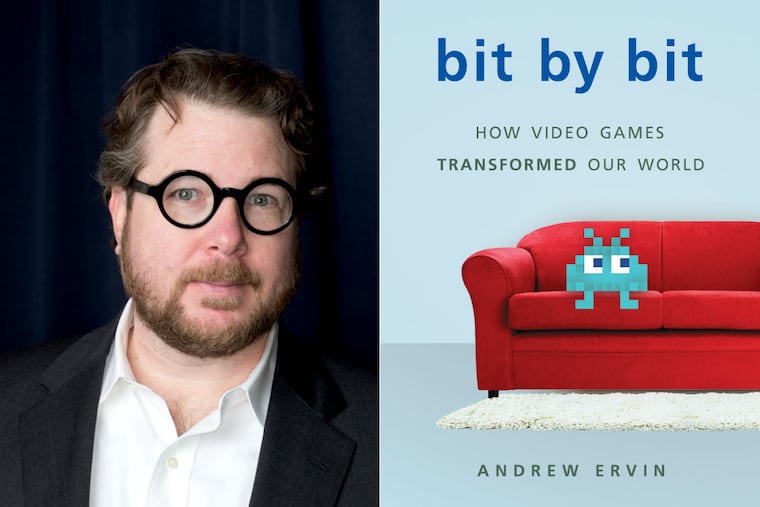

Bit by Bit

How Video Games Transformed Our World

Basic Books. 304 pp. $27 nolead ends

nolead begins

Reviewed by Tirdad Derakhshani

nolead ends If Shakespeare were alive today, he wouldn't waste his time writing plays. Or film scripts, for that matter.

No, he'd be a video game designer.

That's the upshot of a new history of video games from Philly novelist and critic Andrew Ervin (Burning Down George Orwell's House), who claims the video game is a bona fide art form, and its creators the true descendants of the da Vincis, Michelangelos, and Dantes of yore.

Bit by Bit is an urbane, witty, passionate, and eminently literate history of video games from their infancy in the 1950s to today, when they have become so entrenched in the social consciousness that references to Halo and World of Warcraft are part of the common parlance.

Ervin, a Media native, hits all the high points, including the introduction in 1972 of the world's first arcade video game, Atari's Pong; to the 1979 release of Atari's revolutionary game Adventure, one of the earliest open-ended narrative games; to the introduction in Super Mario 64 of the first truly viable 3D environments.

Ervin, who gives equally satisfying treatment to game sounds, special effects, and music, is a terrific storyteller, and he provides profiles of dozens of game developers and fanatics.

I loved his account of the party held in Philly for the 30th anniversary of Tetris in 2014, when two sides of the Circa Centre building in University City were transformed into Tetris game displays. Ervin describes the excitement as he joined the 2,500 gamers who lined up for a chance at a few moments at the keyboards, which were placed across the street.

But Ervin also links the world of gaming to the larger culture, making ample references to the history of art and literature. It's not every day you find Donkey Kong and Rilke rubbing shoulders.

Ervin, who is married to flutist Elivi Varga, deftly mixes personal memoir with social history.

He admits he's never been a committed, full-time vid-game junkie. He was an avid player through his teens, he writes, but he sold his Nintendo system in college to buy books.

He returned to games for the book and found himself utterly bewitched by their sophistication and artistry. While he pays due attention to Halo, he generally eschews shoot-'em-ups in favor of narrative games, arguing that they empower players' creative imagination.

For Ervin, games don't rot the mind. They help it grow and adapt. He writes that playing video games instills in him a sense of calm, some sort of Zen satori that quiets his overcrowded mind.

Yet Ervin also acknowledges that gaming can be highly destructive. He relates the awful story of Chen Rong-Yu, a 23-year-old who died at an internet café in Taipei, Taiwan, after playing a game nonstop for 23 hours.

Ervin doesn't love video games of all stripes. He criticizes the violence of first-person shooters such as Doom and the Halo series. The first-person shooter, he writes, glorifies violence and fetishizes gun culture.

He laments that the military now uses game-playing as a recruitment tool, although he doesn't really provide a persuasive argument for his discomfort. There's nothing inherently wrong with the military's attempts to attract recruits. I think what troubles Ervin is that recruiters may be suggesting that warfare - the blood, sweat, and tears it takes to kill the enemy - can be as easy and comfortable as blowing away zombies on a computer screen.

Above all, Bit By Bit celebrates the artistic achievement and creative power of game-makers. "Shakespeare managed to use the apparent limitations of his medium," writes Ervin at one point. "So, too, in his own way, did [Adventure creator] Warren Robinett."

While this might raise a bemused eyebrow, some of Ervin's larger claims left me genuinely troubled. Surely he exaggerates when he says the development of 3D gaming is as significant a moment in art history as the rediscovery during the Renaissance of linear perspective. More troubling is this passage, which serves as Ervin's thesis statement:

"Today, if there is in fact a distinction between mass entertainment and the fine arts," he writes, "it gets complicated more effectively by video games than any other medium."

Ervin seems to forget that mass entertainment has a purpose outside itself: It is created to sell products, to maximize profit.

Art, on the other hand, serves no master. It has no other purpose than itself. Art has no use-value, except perhaps to transform us as people. Call me old-fashioned, but I believe art doesn't reduce us to mere consumers.

215-854-2736