ARTPOP meets Pop art: Influences on Lady Gaga's new album

Lady Gaga’s ARTPOP could mean anything. At least that’s what she claims in the lyrics of her new album’s title track. But the album’s name alone suggests Mother Monster has more ambitious aims than leaving her work up for interpretation. With ARTPOP, Lady Gaga wants to begin a movement.

Lady Gaga's ARTPOP could mean anything. At least that's what she claims in the lyrics of her new album's title track. But the album's name alone suggests Mother Monster has more ambitious aims than leaving her work up for interpretation. With ARTPOP, Lady Gaga wants to begin a movement.

And like much of the Pop art movement that so heavily influences the album, the artist here isn't so much producing something completely original, as much as she is challenging the way we look at it. Sure the album is full of the sexually-charged club hits we've come to expect from Gaga, but shouldn't that be regarded as art?

To examine the Pop art influences, I went to the Philadelphia Museum of Art and spoke with Erica Battle, Project Curatorial Assistant in Contemporary and Modern Art.

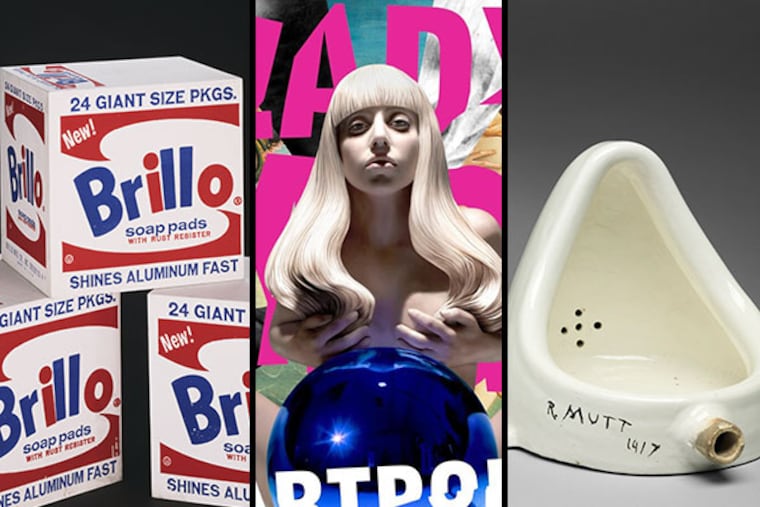

When you step into the modern wing of the museum, you are greeted by a juxtaposition of Andy Warhol and Marcel Duchamp. The pairing is an important one, and draws on the same ideas that took Gaga back to Warhol. Two sculptures flank the main entrance to this wing. To the right is Duchamp's Fountain, a urinal which the artist bought from a manufacturer and brought it to an art exhibition in 1917. The exhibition's organizers, of course, were scandalized and rejected it. To the left is a Andy Warhol's Brillo Boxes (1964).

"Warhol flips [Fountain] on its head," says Battle. "He's very aware of Duchamp and he actually buys a Duchamp. He doesn't go out to the store and buy a Brillo box. He kind of creates his own. But they're made to look exactly like the household item."

When Warhol showed these at an exhibition at the Stable Gallery in 1964, it was another uproarious moment in the art world akin to the commotion that Duchamp started with Fountain almost 50 years prior. 1964 saw not only the explosion of Pop Art, but was also the year that Duchamp produces formal editions of his work.

Flash forward 50 years and we have Lady Gaga sparking similar uproar every time she steps out onto the red carpet. Gaga's outfits might be provocative, but her art doesn't stir up the same kind of controversy. The Pop art movement was not initially met with critical acclaim. So far, ARTPOP has received reviews mostly ranging from lukewarm to positive.

"The kind of paradigm that [Warhol] set up is that an artist is not only an artist that makes an original work," said Battle. "An artist is kind of a leader of a larger—what he called, a 'factory'—actually a factory in which work can be made."

For Gaga, the product she seeks to create is celebrity. The pop star behind such albums as The Fame and The Fame Monster works in a factory that produces pop culture. Every stunt she pulls-- from being carried into award shows in an egg, to her 2015 plans to sing in space—has pop culture relevance. In her songs, whether it's "Fame" or "Applause," she makes no secret of her motivation.

"'Applause' is a very meaningful song to me, because it addresses what many think of as 'celebrities' today, that we 'do it' for the attention," Gaga recently wrote on Twitter. "But some of us are 'artists' in this group called 'celebrity,' & what we create doesn't live on unless there's an audience to remember it."

For her album cover, Gaga commissioned York, Pa.'s Jeff Koons, who along with contemporary post-Pop artists like Damien Hirst and Takashi Murakami, works in that same kind of factory paradigm. When buying a Jeff Koons piece, consumers understand that Koons may not have actually himself made the work himself. That doesn't stop them from shelling out millions for one of his plaster sculptures with blue "gazing balls."

Gaga holds one of these gazing balls in her plaster cast lap in her Koons album cover, complete with a shattered Botticelli behind her. Koons is considered the most successful American artist since Warhol. And like Warhol, Koons comes from a background in advertising.

"So you have people that had been working with the market in a very different way and then going into art, and not vice versa, which is usually the case," adds Battle.

Lady Gaga might not share that former vocation, but when it comes to advertising, she knows at least one thing: Sex sells. That much is clear when listening to her latest album. Tracks like "Venus," "G. U. Y." (Girl Under You), and "Sexxx Dreams" represent her most salacious lyrics since singing about her desires to take a ride on a disco stick.

"[Advertising] is where you get a lot of the pop imagery and iconography," said Battle. "You get it from Warhol who is looking at real people like Marilyn Monroe and Jackie [Onassis], but then in advertising you also get the beefcake male, you get the pinup, the housewife, the household product, and all of those images start proliferating through PopArt."

Celebrity and recognizable imagery remain common themes among both Pop art and pop music. One of the most recognizable images to Americans is the American flag, which became an important link between the work of Jasper Johns and Pop.

"This flag again becomes very Pop-related," said Battle. "[Johns] does the flag in 1954 and by the 60's this flag is everywhere. This is one of those images that Pop itself appropriates."

Art dealer Leo Castelli even gave John F. Kennedy a Jasper Johns flag as a gift. In the same room as Flag is another Johns work that serves as a more straightforward Pop piece, his Ballantine Ale Cans. Like the Brillo boxes and the urinal, "[Johns is] making something that is very straightforwardly low brow and turning it into a high brow art object," said Battle. "This is taking beer cans and actually casting them in bronze and painting them trompe l'oeil style so that they look and feel like beer cans."

Ballantine was the official beer of the Yankees, so lowbrow indeed.

"He's kind of presenting them, and he gives them this little pedestal, so it's kind of like lifting them even more slightly into the realm of art. I think it's really such a great piece. And it's so Johns."

With ARTPOP, Gaga is doing something very similar. The album name itself acts as a pedestal. She's taking what might ordinarily be considered common, lowbrow pop songs and demanding that they be viewed as art. Such presentation might seem bold or even delusional from someone else, but for the artist formerly known as Stefani Germanotta, humility is a foreign concept.

She is obsessed with celebrity, and much like Warhol, she welcomes the fame. There's an apocryphal story about Warhol, the man who coined the idea of "15 minutes of fame," and the moment in Philadelphia that catapulted him to superstardom. During a 1965 Warhol exhibit at the Institute of Contemporary Art on UPenn's campus—the artist's first solo show-- the crowd reportedly grew so large and unruly that Warhol turned to his entourage and decided they had to get out of there. Legend has it that Warhol and friends, including Edie Sedgwick, escaped through a false ceiling. Whether or not Warhol needed to make such a dramatic escape, the Pop art god didn't exactly shy away from his new celebrity status.

"That kind of idea of artist and myth, Warhol is a master of that," said Battle. "He embraces it and perpetuates it. He's totally a celebrity in and of himself."

Warhol may have mastered the idea of celebrity, but Gaga is doing her best to match him, albeit with a very different approach. While she maintains a great relationship with the "Little Monster" fans that adore her, the roles are clear: She is the celebrity, and they are the fans. She doesn't seem to have any interest in disturbing that hierarchy. Not all Pop artists, however, saw it the same way.

One of the museum's other great juxtapositions are Robert Rauschenberg's "Combine" from 1956, and his 1963 work, "Estate." Rauschenberg, who was not a rich artist during 1950s, decided to reuse a canvas from one of his older white paintings and remade it as a collage using what he had lying around.

"The combines are-- and in Rauschenberg in general-- is about leveling the hierarchy of everything," said Battle. "So in the same combine, we can have an image of the Mona Lisa and the image of a comic strip. Rauschenberg's famous quote is he 'operates in the gap between art and life.' That's kind of an idea that's in the air at the time with Duchamp and other artists, that there is no hierarchy any more between art and life."

Warhol revered Johns and Rauschenberg, who were already enjoying success while he was still trying to figure himself out as an artist. Gaga often cites Warhol as an inspiration, and channeled his work for this album.

"The intention of the album was to put art culture into pop music, a reverse of Warhol," Gaga told the Daily Mail. "Instead of putting pop onto the canvas, we wanted to put the art onto the soup can."

It's difficult to claim that she accomplished that. With the exception of a possible reference to Koons, there isn't much about art culture to be found on this album. Most songs, while occasionally racy, lack the shock value that one might expert for an album with so much fanfare. They have the accessible qualities of Pop art, but not the subversive undertones.

"There's a subversiveness and a criticality that exists in Pop art that is easy to miss, but is really there," Battle said. "Pop is actually easy to swallow, but once you swallow it, you might realize that it was really something else."

The relationship between Pop art and music is not a new one. Warhol worked with the Velvet Underground and the band used a Warhol banana as their album cover. Peter Blake's cover for the Beatles' "Sergeant Pepper" album was a major moment for pop and music, and is still revered as one of the best album covers of all time.

Gaga may not have successfully captured all of the themes of Pop art, or blazed a trail for a new genre of music, but the songs are still enjoyable, and the artistic influence of Pop art are definitely worth exploring at the Museum of Art.

In addition to the museum's holding from major Pop artists like Warhol, Rauschenberg and Roy Lichtenstein, there are other works that are both Pop relevant and ARTPOP relevant.

Paul Thek was in no way a Pop artist, but his Meat Piece with Warhol Brillo Box takes on special significance when we recall how scandalous a piece of raw meat can be. Think Lady Gaga's meat dress at the MTV Video Music Awards. Thek saw Warhol's Brillo boxes when they were shown in 1964. He bought one, gutted it out, and one year later displayed it with a large piece of meat. One major difference between Thek and Gaga: Thek used trompe l'eoil. Gaga's dress was real meat.

One of the more quintessential Pop pieces in the collection is James Rosenquist's Zone (1961) and features a close up of a woman spliced with a tomato. We can only assume Gaga's tomato dress is still to come. Claes Oldenburg's Miniature Drum Set (1969) is a fine example of the kind of soft sculptures that appeared inflated and deflated at the same time. Oldenburg created a similarly constructed melting ice cream cone that he strapped that to the top of his Volkswagen and drove around. Now that sounds like Gaga.

In February, Battle and Philadelphia Museum of Art will host an exhibition showcasing examples of Pop art to now. "Revolutions of the Real" (working title) is part of the "Notations" series in the Contemporary Art gallery and will feature some quintessential Pop Pieces.

Until then, you can check out the Pop art holdings with Gaga's ARTPOP blaring through your earbuds, and you can be the judge of whether Mother Monster captures the movement.