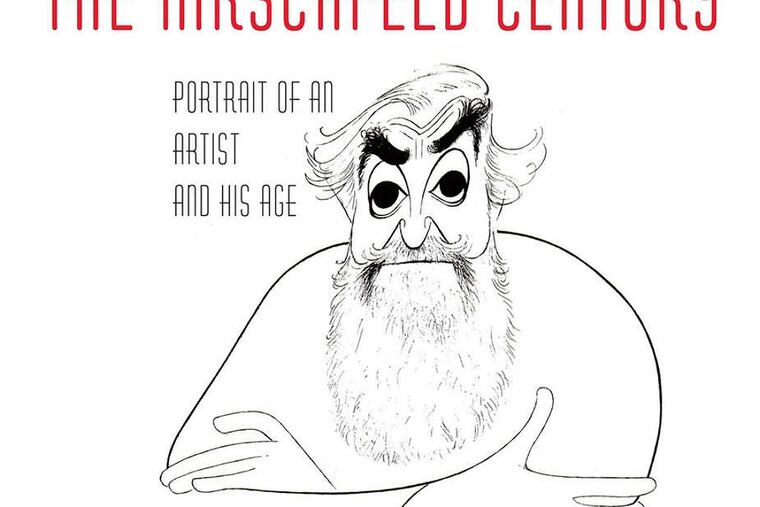

In new book and exhibit, the Al Hirschfeld legacy continues

With a certainty that's rare anywhere, much less on Broadway, Al Hirschfeld's drawings accompanied the opening of most major New York shows for a showbiz eternity - the 1920s to his 2003 death at age 99 - drawing viewers into that world with a veracity photographs rarely touch.

With a certainty that's rare anywhere, much less on Broadway, Al Hirschfeld's drawings accompanied the opening of most major New York shows for a showbiz eternity - the 1920s to his 2003 death at age 99 - drawing viewers into that world with a veracity photographs rarely touch.

The illustrations are more than frozen moments - rather, they capture a sense of evolution in progress, whether Liza Minnelli in mid-song or American theater in transition.

"He always felt that we all have this ability to recognize a friend from the back, a block away, wearing an overcoat. He didn't know how we do that. But he was always going for that telling gesture, that arch of the eyebrow," said David Leopold, the archivist and curator responsible for much of the current flurry of Hirschfeld commemoration.

The Hirschfeld Century is the title of both a new, lavishly illustrated coffee-table book (Knopf, $40) and a New York Historical Society retrospective through Oct. 12, both authored and curated by Leopold. As someone who has seen more Hirschfeld drawings than anyone other than the artist himself, the Bucks County curator readily dissects why these seemingly disposable caricatures - about 10,000 - outlive the people they document.

"Hirschfeld didn't have a formula. He didn't approach anybody the same way. If he thought he was doing what he did before, he would stop the drawing," Leopold said. "The piece of paper doesn't care how many awards you have. It only cares about the graphic question you're posing today."

Certain ideas recur, such as playwright George Bernard Shaw pulling puppet strings from heaven. But were Hirschfeld a mere caricaturist, he wouldn't have found his way into the inner lives of the actors playing the character. "How you manage to get inside of me and interpret my movements . . . is a source of constant amazement to me," actor Ray Bolger wrote in a note to Hirschfeld. "Perhaps you are my alter ego - or . . . perhaps I am yours!"

Reactions weren't always uncomplicated. Carol Channing didn't see herself in his drawings, but her father. Sometimes Hirschfeld hated his own work, refusing to let Geraldine Fitzgerald buy her Shadow Box portrait, claiming "I'm going to set fire to it."

What seemed to be accomplished with the graceful flick of a pen in fact evolved over time. It started with out-of-town tryouts in Philadelphia, where he watched not for a show's plot, but for important moments, often sketching inside his pocket as the show went on, with his gift for eye-hand coordination. "It was like typing," says Leopold. "You do that without looking."

Back in New York, he sometimes went through hundreds of drafts to create his typical flowing, buoyant theatrical landscapes in time for preopening publication. His one foray into actually writing a musical was a show titled Sweet Bye and Bye. It failed - but it did yield the now-classic drawing "Death in Philadelphia," showing Hirschfeld and collaborators Ogden Nash, Vernon Duke, and S.J. Perelman crowded into a hotel room strewn with coffee cups while desperately trying to salvage their flop.

There were other creative snags. "He struggled with Paul Newman in Our Town," recalled his third wife and widow, Louise Kerz Hirschfeld. While drawing Oscar Hammerstein II, Hirschfeld worried that the famous Sound of Music lyricist came out looking inebriated. Returning from a summer vacation, Hirschfeld parked himself at a window table at the Times Square Howard Johnson's, drawing passersby to get his chops back.

Also an accomplished easel artist, the St. Louis-born Hirschfeld studied painting in London and Paris in the 1920s; the lack of hot water for shaving prompted him to grow his trademark beard. A lucky break landed his illustrations in the New York Times, beginning a relationship that lasted roughly 75 years.

Although the evolution of his style began with influences from noted illustrators of his time, a turning point occurred in a visit to Bali: The sun bleached out so many details in the humanity around him that he began to see the world as a series of line drawings.

Yet much of his work went well beyond lines, sometimes in lithograph form, whether portraits of Manhattan speakeasies in the 1930s, full-color 1940s MGM movie posters, or 1970s Kabuki illustrations. Most penetrating are late-1920s drawings from Moscow. Our sense of Hirschfeld might be different if an entire book of Russian drawings hadn't been lost by his publisher. "The only time I saw regret cross Al Hirschfeld's face," said Leopold, "was in discussing that book."

As it is, Hirschfeld was Edward Hopper on helium, crystallizing a real-life moment, and often its inner psychology, giving corkscrew eyes to the intensely comic Lucille Ball and something more demented to Sarah Brightman in Phantom of the Opera. Later drawings had breathtaking spareness. A single green line conveying Liza Minnelli's arms and shoulders captures the singer's openhearted but tightly wound physicality.

One of the few possible failures was at the end: A 2002 collage of Philadelphia Orchestra music directors from Leopold Stokowski through Christoph Eschenbach. Only Stokowski, whom Hirschfeld knew, has much personality. Riccardo Muti is unrecognizable.

"I would say that if you want a photographic likeness, you hire a photographer. I think it's great drawing," says Leopold. "And though the documentary aspect of a drawing is important, that changes, like with Toulouse-Lautrec's posters of Jane Avril. The drawing is more important than who it is."

More than an advocate, Leopold admits his early life was hijacked by Hirschfeld. It started with a phone call (the artist's number was listed) regarding a theatrical illustration project - and that led to Leopold's hiring as Hirschfeld's archivist.

"I would go to his studio once or twice a week starting in 1990. When there was something I found and couldn't figure out what it was, he'd say, 'Where did you find that?' And some great story would tumble out," said Leopold, who has gone on to curate a number of pop culture exhibits, including the current Everything is Dead show (as in the Grateful Dead) at Chicago's Field Museum.

The closer one got to Hirschfeld, the more his life looked like its own kind of show. Dinner guests included Woody Allen, Carl Reiner, and Dame Edna creator John Barry Humphries, often vying with one another with stories about the worst performing conditions they'd ever experienced. "It was a feast of laughter," Louise Kerz Hirschfeld said. "Walter [Cronkite] said it was the best show he'd ever gone to without paying."

And it's a show that might never post closing notices.