Galleries: Two artists in rooms of their own

It's not especially common for two artists with thriving individual careers to work collaboratively, but spouses Chris Johanson and Johanna Jackson realized that the way they live in Los Angeles (and previously in Portland, Ore., and San Francisco) - whet

It's not especially common for two artists with thriving individual careers to work collaboratively, but spouses Chris Johanson and Johanna Jackson realized that the way they live in Los Angeles (and previously in Portland, Ore., and San Francisco) - whether growing vegetables, cooking, building furniture with scavenged wood, or making their own housewares - constituted a perfectly legitimate kind of art. Perhaps even a more socially responsible and personally relevant "art" than the works they had been making on their own, though both continue to exhibit as individual artists.

That shared philosophy has led to several collaborative exhibitions, most recently their site-specific installation, "House of Escaping Forms," at Fleisher/Ollman Gallery.

So what do Johanson and Jackson's "life arts" - Johanson's designation - look like?

At first, Fleisher/Ollman's unusually wide-open gallery space gives the impression of a furniture showroom designed by Pee Wee Herman - and I mean that as a compliment to the artist duo and to the Paul Reubens character. It's dominated by three open, roomlike structures built by Johanson that suggest stage sets of domestic interiors and that are painted in various shades of purple and blue (this could easily have turned garish, but it makes for handsomely offbeat combinations).

A "bedroom" and a "living room" sit on raised platforms fashioned from shipping pallets; a "dining room" sits directly on the floor. All three rooms are filled with the furniture and objects you might expect to find in them, all made by the artists except for the found wood used in the construction of the rooms, and the used pallets and unused acrylic paints obtained at Revolutionary Recovery, a Philadelphia demolition debris recycling center. This is about as DIY as it gets.

Unless you're versed in the work of Johanson, a painter and installation artist who came of age with the San Francisco art scene of the latter 1990s as a member of its Mission School, and that of Jackson, a painter also affiliated with that school who has since turned to textiles and ceramics, it's not obvious which works are his, hers, or theirs. (Johanson showed his work here, at the ICA, in 2001, in "East Meets West: 'Folk' and Fantasy from the Coasts," organized by Alex Baker, now director of Fleisher/Ollman.) So carry the gallery's checklist around with you; the authorship of these works is unpredictable and interesting to know.

Jackson's hooked rug in the "living room," made with yarn she hand-dyed using such natural pigments as cochineal and indigo, and a knitted sweater hanging in the "bedroom" closet are especially impressive, as are her ceramic pieces and Johanson's thick, delicately colored (pink, amber, yellow-green) cast-glass drinking vessels.

Though I understand Jackson and Johanson's decision to hang their collaborative paintings on the gallery walls as a way to convey the experience of seeing physical emanations of domestic interiors beyond their circumscribed allotments of real space (hence the exhibition's title), such as a painting of the interior of a medicine cabinet that suggests a real medicine cabinet hanging on the wall, the casual loopiness of some of these works seems defiantly at odds with the installation's more carefully made works that display an attention to detail.

Call me tidy, but I'm glad the escaped forms escaped Johanson and Jackson's house.

Fleisher/Ollman Gallery, 1216 Arch St., 10:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Tuesdays through Fridays; noon to 5 p.m. Saturdays. 215-545-7562 or www.fleisherollman.com. Through Jan. 30.

Two to see now

Two terrific shows at the Berman Museum of Art at Ursinus College have only two more days to go.

Lynn Chadwick, an admired postwar British sculptor (1914-2003) whose honors included the International Sculpture Prize at the 1956 Venice Biennale and whose works were fervently collected by Philip and Muriel Berman, forming a substantial part of the Berman Museum's collection, is the star of "Tyger, Tyger: Lynn Chadwick and the Art of Now."

The exhibition, organized by Berman curator Ginny Kollak, who took inspiration from the William Blake poem "The Tyger," pairs Chadwick's smaller, cast-bronze sculptures of abstracted humanoid forms with works by contemporary artists who would seem to share Chadwick's interest in expressing emotion through timeless, mythologically inspired renderings of the human form.

In most cases, Kollak's selections echo Chadwick's evocations of existential despair and the attenuated forms of his sculptures. Fearful symmetry abounds.

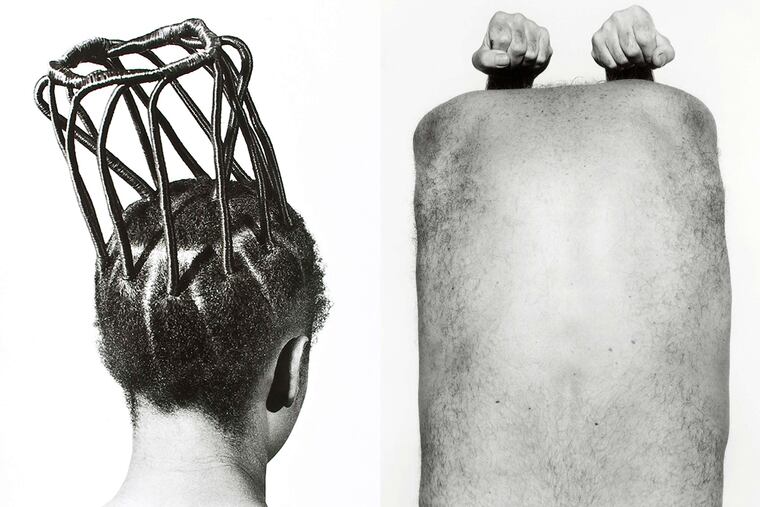

This is most obvious in the late John Coplans' black-and-white photographs of his own naked, aged body, posed to suggest cropped views of sculptures. (Here, looking at Coplans' photographs, which I had seen many times before in various venues, I realized I had seen aspects of Chadwick's sculptures in them before but had not made that connection).

Ruby Sky Stiler's tactile assemblages, Nick Cave's alienlike mannequins; Louise Despont's diagrammatic drawings on antique ledger book pages; Anya Kiefar's paintings of primitive forms that suggest cave paintings as reimagined by a modernist, and the late J.D. Okhai Ojeikere's photographs of Nigerian women's elaborate, sculptural hairstyles round out the group.

Upstairs, a show of Joel Meyerowitz's unflinching photographs of the World Trade Center site in the immediate aftermath of the buildings' destruction on Sept. 11, 2001, are as wrenchingly sad as ever.

The Philip and Muriel Berman Museum of Art at Ursinus College, 601 E. Main St., Collegeville. 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesdays through Sundays. 610-409-3500 or www.ursinus.edu. Through Dec. 22.