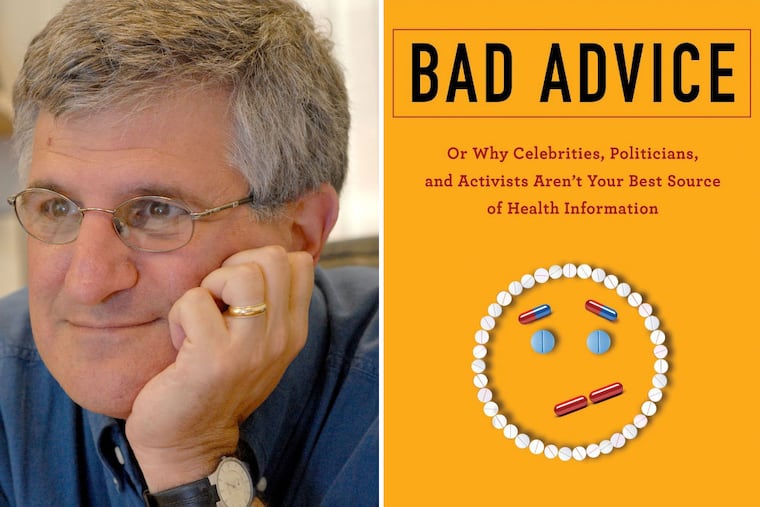

‘Bad Advice’ by Penn scientist Paul A. Offit: Take back the science conversation in our culture

In his new book, "Bad Advice," Penn scientist Paul A. Offit argues that scientists are the best source of information about science, not those popular misinformers, celebrities and politicians. In breezy but serious prose, he argues that scientists must act to take back the science conversation, or science itself risks losing its rightful place as "a source of truth."

Bad Advice

Or Why Celebrities, Politicians, and Activists Aren't Your Best Source of Health Information

By Paul A. Offit

Columbia. 251 pp. $24.95

Reviewed by Karen Iris Tucker

In Bad Advice, Paul A. Offit, a pediatrician, scientific researcher, and director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, argues that scientists should immerse themselves much more proactively into our popular discourse to help educate the public.

While Bad Advice is a quick read, its goal is weighty: to defend science as a vital beacon in the public sphere. Offit argues that we need to protect its honor, and he calls for scientists to "become an army of science advocates out to educate the country. Because science is losing its rightful status as a source of truth, now is the time."

In breezy and deceptively conversational prose that often winks with humor, Offit takes to task actors, network news anchors, quack scientists, and even politicians who have opined on scientific subjects in a way that misinforms the public, on occasion to a potentially dangerous degree.

Offit has spent years navigating media appearances as a medical and scientific expert. A co-inventor of RotaTeq, a vaccine against rotavirus, Offit has become a high-profile voice on vaccine safety and, in particular, an ardent defender of the scientific community's consensus that vaccines have no association with autism. He cites several recent outbreaks of measles and mumps across the nation because some Americans are choosing to withhold vaccines from their children.

Beyond the sizable list of celebrity activists such as Jim Carrey, Charlie Sheen, Robert De Niro, and Jenny McCarthy who have questioned the safety of vaccines, Offit says the current political climate bears some culpability for what he calls "science denialism." He points out that before being elected, President Trump posited the idea that vaccines may have an association with autism. Offit also says evolution denialists were probably heartened by Trump's choice of Mike Pence as vice president since Pence doesn't exactly support evolution as a concept.

Across the aisle, Offit says, "liberals have waged their own war on science, holding the unshakeable beliefs that all things natural are good; anything with a chemical name is bad." He points to the fallacy of going "GMO free" — in the mistaken belief that genetically modified organisms are dangerous. Health organizations worldwide have consistently issued statements to the contrary. Similarly, the misguided fear of genetic modification in medicines (a technology, for example, that led to the creation of insulin for people with diabetes) inspired a Democratic member of the New York State Senate, Thomas J. Abinanti, to introduce a bill in 2015 banning genetically modified vaccines. It rightfully failed to win support.

Offit also tackles the current gluten hysteria, citing the ever-expanding array of gluten-free items on our supermarket shelves, from hair products to pet food. "If you really want to watch science denialism at work, just walk into a Whole Foods store," Offit half-jokes. He says only about 1 percent of the U.S. population would benefit from avoiding gluten. It is nevertheless a billion-dollar industry here.

Although scientists are probably in the best position to explain science to the public, Offit contends, there are several factors working against them. One, he says, is the very underpinning of their training, which teaches that the scientific method does not allow for absolute certainty — something people tend understandably to crave in the face of public health scares.

There's also the ingrained image of scientists as socially awkward toilers in white, windowless rooms. By way of illustration, Offit cites the brutal pickup line by mathematician John Nash in the 2001 movie A Beautiful Mind: "I don't exactly know what I'm required to say in order for you to have intercourse with me." Offit shows how such depictions have persisted through today, including in the hit television show The Big Bang Theory (which actually features real-life high-profile scientists).

Like the nerds in those cultural touchstones, Offit admits in Bad Advice, which chronicles many of his media appearances, that it took some time for him to master the art of distilling vital medical information into on-air sound bites. For one network television appearance in his younger days, Offit recalls teetering on a high, wobbly chair, with an ill-fitting earpiece, waiting to answer questions about vaccines. When his chance finally came, Offit, then a newbie to on-air interviews, booted it.

Despite its liberal use of such lighthearted anecdotes, Bad Advice does not let us forget its weighty contention: Science is under siege. Offit closes his book with recollections of a speech he gave at the March for Science in Philadelphia in 2017. In it, he implored his fellow scientists to be better advocates and educators. Failing that, he says, "I worry that in this age of anti-enlightenment, when science seems to be losing its place as a source of truth, we won't be able to do it for much longer."

Tucker is a Brooklyn-based journalist who writes primarily about genetics, health and cultural politics. This review originally appeared in the Washington Post.