EgoPo’s ‘A Human Being Died That Night’: An intimate struggle of forgiveness and accountability

A Human Being Died That Night opened on Friday at EgoPo Classic Theater, intended to start a larger conversation surrounding race relations in America.

The stage adaptation of Pulma Gobodo-Madikizela's award-winning book A Human Being Died That Night opened Friday at EgoPo Classic Theater as a part of its 2018-19 season focusing on theater of South Africa, intended to start a larger conversation about race relations in America. The play's motif is the principle of forgiveness, racism, and the nature of reconciliation.

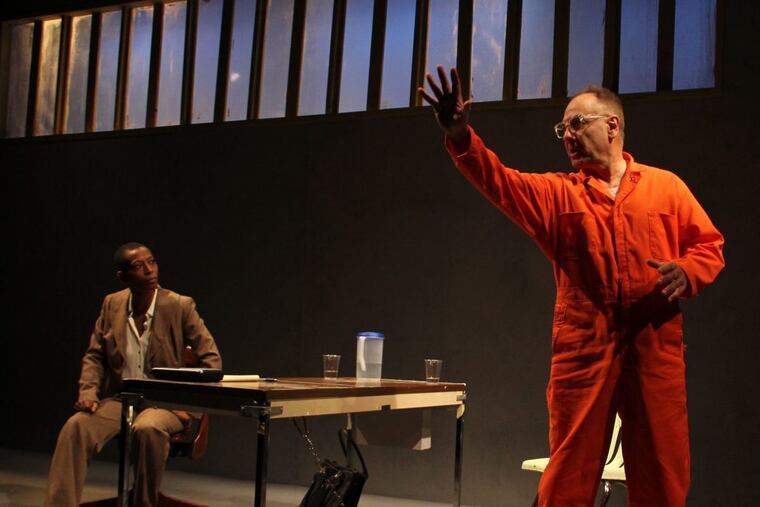

Sounds of Hugh Masekela and other South African singers serenaded the audience as they found their seats in the intimate EgoPo theater. The dimly lighted stage was set with two chairs on opposite sides of a desk bolted to the floor. The play opened with a brief monologue by Pulma (Niya Colbert) — one of only two characters in the play — providing context to South African apartheid and her role in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Her job was to interview an incarcerated Eugene de Kock (Paul L. Nolan), a white ex-police officer who earned the nickname Prime Evil for the atrocities he inflicted on black people.

Pulma posed penetrating questions of Eugene, who was chained to the desk, symbolizing his volatile nature, in an attempt to unravel the threads of his twisted motives and perhaps discover his humanity. Though Pulma tried to maintain a sense of objectivity and professionalism, she found herself emotionally invested in Eugene's story.

The play was held together by strong acting skills. Nolan's vibrato and Colbert's ability to portray empathy added color to what could have been an otherwise dull script. For a cast of two, the performances were engaging. Both actors soared through their lines with ease and conviction. But the play suggests an oversimplification of forgiveness. Is confession sufficient in the aftermath of atrocities? Is confession a balm for victims' pain? How does one approach accountability with respect to forgiveness? These are all questions the play had an opportunity to address or explore further. But, alas, it did not.

A Human Being Died That Night isn't a work of opulence. Its meaning is in these two characters' discovery of what it means to be human. With its focus on a precarious time in South Africa as the country came to terms with its past and future, this play serves as a catalyst for conversations about human rights and forgiveness.