Eliza Griswold’s ‘Amity and Prosperity’: Fracking, profit, and human costs in western Pa.

In Eliza Griswold's beautifully researched and written chronicle, people living in Marcellus Shale country encounter powerful energy companies, bumbling government agencies, and persevere.

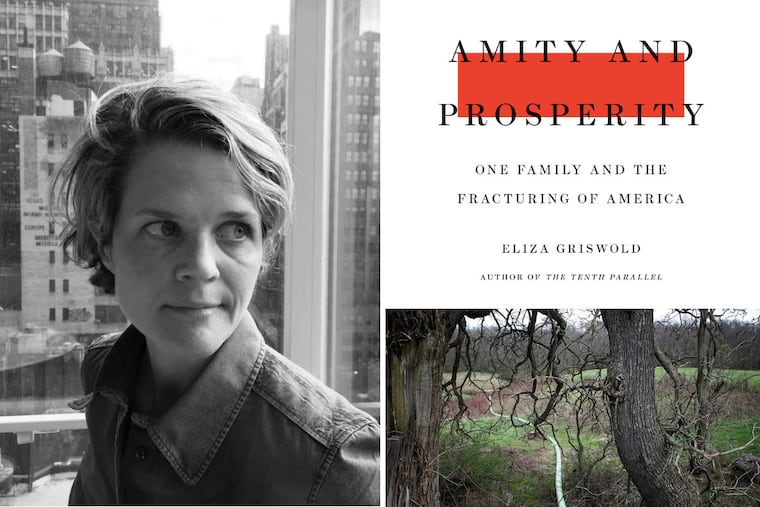

Eliza Griswold says her new book, Amity and Prosperity: One Family and the Fracturing of America (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, $27), "is about the price of energy." More than seven years in the making, Amity and Prosperity studies Marcellus Shale families in Washington County, Pa., and their encounters with big energy and its pluses and minuses.

Range Resources, one of the biggest oil exploration companies operating in the Marcellus Shale Deposit, comes to the town of Amity, bringing the severely mixed blessings of the fracking era. Range improves roads and infrastructure, injecting millions into the local economy. But families like that of single mother Stacey Haney, whose story is chronicled here, start to get ill. Their pets sicken and die. High levels of arsenic and other compounds are found in their blood.

Three families sue the company, and after years of wrangling, their case goes all the way to the state Supreme Court, which finds in their favor.

Griswold is an eminent investigative reporter, author (The Tenth Parallel), and poet. She spent several of her growing-up years in Chestnut Hill, as the daughter of the Rev. Frank T. Griswold III, rector for more than a decade at the Church of St. Martin-in-the-Fields. She spoke with the Inquirer on both ends of a flight from Pittsburgh to Philadelphia.

Despite environmental crisis, illness, and personal hardship, the communities involved are split about whether it was all worth it. "Some feel that price was worth paying," you write at the end. "Others don't." Isn't that part of the story? That we can't agree about fracking, or the balance between economics and the environment?

There's no divorcing energy from politics. The book is an effort to listen to people who lived with the costs of energy and see what their view of those costs are. They themselves have conflicted opinions.

Their suffering is real enough.

Stacey and her neighbors were pro-fracking for years. They saw it as pretty much a patriotic duty, a way to make America great again. But as their troubles multiplied, they were disillusioned, not just with fracking or industry, but also with government, which showed such incompetence and negligence in regulating industry and protecting citizens.

But that's the point: It's easier to be negligent with marginalized populations. As for the suffering – what got me started on this book was the realization that all over the world, some of the poorest people live on the land richest with resources, closest to the most concentrated pollution. And we now are seeing that same pattern in our country.

You're on a book tour. And you went back to the scene of the book.

Two nights ago [June 20], I was in Washington, Pa., and much of the town of Amity showed up at what was supposed to be a book event. It turned into passing the mic around and getting people to tell their own stories. It was like being inside the book. Stacey's sister Shelly spoke.

Many people around the world live the quiet horror of environmental catastrophe every day. They often have no one else to tell their stories, but that doesn't mean they don't exist. One person stood up and talked about the Yeager property, which has become the center of the controversy. The family that used to own the farm were there, and now it's an industrial site.

The Yeagers are interesting: They're wealthy, business-wise. They believe they're being smart in selling their land to the company, but things go wrong.

Yes, all the neighbors got in over their heads. These are, for the most part, highly intelligent people who, to some degree, thought that their savvy would set themselves apart from their neighbors. But the company controls the information, so you can't know what's going to happen, what chemicals are being used.

In many cases, the company reps don't even know, because they are subcontracting out to companies whose chemicals are proprietary. Regulators rely on the industry for the information they need to regulate that industry – so how is that supposed to work?

So much here reminds me of what I see as a war reporter. The problems of subcontracting. The tendency to pass the buck: 'I'm not responsible, it's eight companies down.' The dark side of privatization.

Why don't we read these people's stories more often?

Last night [June 21], I was in Pittsburgh, talking to Don Hopey, environmental reporter for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. We were saying that the real story is often how privatized profit coexists with public poverty. And he said, 'It's not just industry and not just the government. The press are involved in not telling the story.'

The truth is, papers often no longer have the funds to do it. Part of the service of a book like Amity and Prosperity is telling some of those stories, the kind that take resources to research and tell. I've been talking to other reporters about how we can do a better job.

You say you find room for hope.

Several things made me hopeful. Two such people are John and Kendra Smith, who take the case all the way to the Supreme Court, trying to fight this industry on the basis of an obscure environmental amendment in the Pennsylvania Constitution that states the right of citizens to clean water and air.

And you have a generally conservative court, including Ron Castille, the chief justice, by no means a liberal man, and they uphold the amendment for the first time in history, giving it practical teeth.

He even quotes Stacey in that decision. For her, it's the most important thing she's done in life besides having her children. On this issue of protecting our most basic rights, conservatives and liberals came together, when so often they are bandied about between right and left. Their decision affirmed the validity of these people's experience.

That's what I'm finding on this book tour. It gives me hope to hear people speak. It affirms the authority in the words of those who have endured.