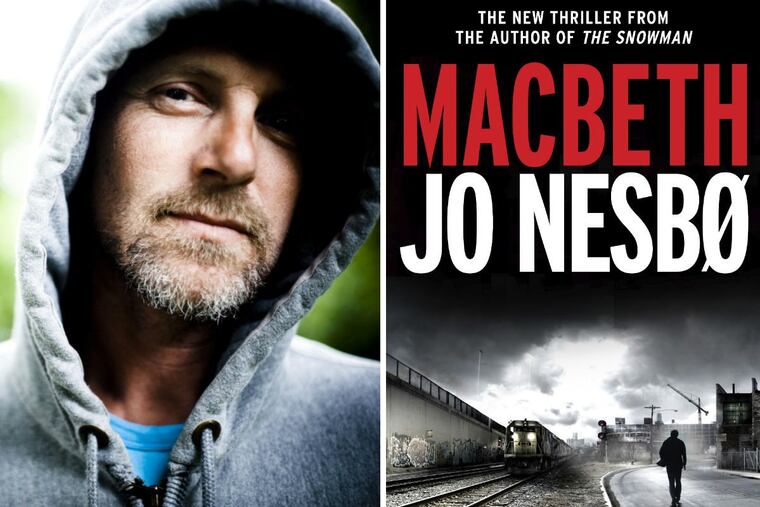

Jo Nesbø's 'Macbeth': A Norwegian noir master takes on 'the Scottish play'

Jo Nesbø's "Macbeth" resets Shakespeare's bloody tragedy in a modern state wracked by authoritarian rule, corporate greed, and addiction.

Macbeth

By Jo Nesbø

Hogarth. 446 pp. $27

Reviewed by Dennis Drabelle

In Norwegian novelist Jo Nesbø's adaptation of Macbeth, we come to the novel not only knowing how the play turns out (not so hot for the title character), but also with a cauldron of memorable features bubbling in our brains – the soothsaying witches, the compulsive hand-washing, Banquo's ghost, and at least a smattering of the poetry: "Out, damned spot," life is "a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing," etc. Here, the fun comes from watching a crack storyteller put his noir stamp on one of Shakespeare's greatest tragedies.

The new Macbeth takes place circa 1970, not in a kingdom but in a nominal democracy with a tendency to elect strongmen. By eliminating rivals and superiors, Macbeth hopes to slay his way into the mayor's office of the industrial city in which he lives, and then – well, to borrow from another Shakespeare play, perhaps there will be a tide in his affairs, taken at the flood.

To help the play's heaping doses of mayhem go down, the author makes some crafty choices. Many of the main characters, Macbeth included, ply a trade in which killing with impunity is relatively easy: police work. To provide plausible modern substitutes for ghosts, Nesbø hooks many of his characters on a drug called (rather heavy-handedly) "power," which can induce frightful hallucinations. To make the drug kingpins au courant, the author endows them with a libertarian strain. "My religion is capitalism," one of them explains, "and the free market my creed." And Nesbø adds another layer of addictive behavior by making casino gambling his imagined country's national pastime.

In Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare, Stephen Greenblatt astutely points out that the Macbeths are Shakespeare's most convincing portrait of a devoted couple. Nesbø takes care to explain why they delight in each other. In a drug lord's words, Lady, as she is simply called, is Macbeth's "beloved dominatrix." In turn, she views his submissiveness as an asset, exulting that he loves "that part of her which frightened other men. Her strength. Willpower. An intelligence that was superior to theirs and that she couldn't be bothered to hide under a bushel. It took a man to love that in a woman."

Nesbø tinkers with some elements of the play, as when he changes Caithness' gender from male to female. He had every right to do that sort of thing, even to skip certain episodes entirely – his fulfillment of the Birnam Wood prophecy is so over the top that he might just as well have left it alone. On the whole, though, Nesbø manages to be true to the original play without slighting his own interests as a writer: bleak settings, loyalty (or the lack thereof) among crooks, clever escapes from tight spots, the affinities between policemen and the criminals they chase.

Nesbø's Macbeth is the latest entry in a project in which top-flight novelists are asked to reinterpret Shakespeare. Already published are Jeanette Winterson's The Winter's Tale (retitled The Gap of Time), Howard Jacobson's The Merchant of Venice (Shylock Is My Name), Anne Tyler's The Taming of the Shrew (Vinegar Girl), Margaret Atwood's The Tempest (Hag-seed), Tracy Chevalier's Othello (New Boy) and Edward St. Aubyn's King Lear (Dunbar). This is heady company for a crime novelist to join, but Nesbø has repaid what may have been a wild hunch on the part of his publisher.

Near the end of the novel, Macbeth raises his hand to give a certain door a momentous knock. He stares at that hand, expecting it to betray "the seven-year tremble. He couldn't see one. They said it was worse when there wasn't one, then it was definitely time to get out." That missing constabulary tremor is a nice touch, an embellishment of Shakespeare that is all the more striking when you recall that Macbeth is indeed about to "get out," though not the way he intended.

Dennis Drabelle is a former mysteries editor of the Washington Post Book World.