Poems vibrating with war, love

Yusef Komunyakaa's 12th volume is an atlas of slaughter, of issues that will not go away.

Poems

By Yusef Komunyakaa

Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

96 pp. $24

Reviewed by Karl Kirchwey

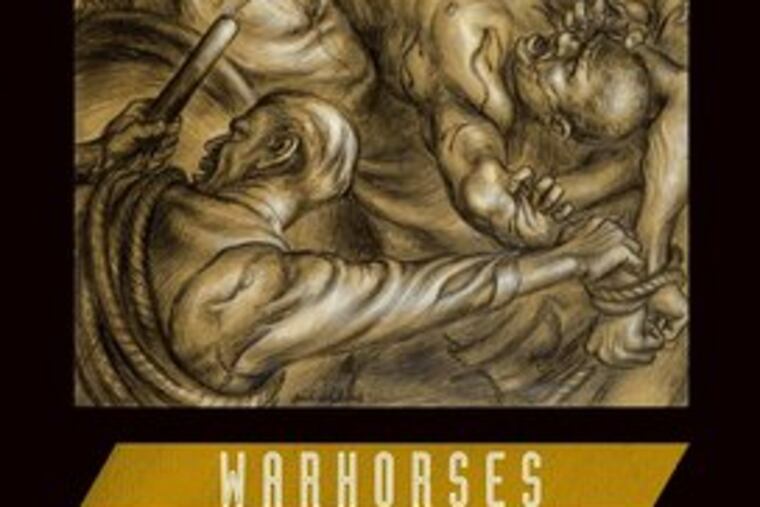

A first glance at the cover art of poet Yusef Komunyakaa's 12th book suggests it is a sculpture or bas-relief in bronze by a Renaissance master like Verrocchio. Everything is a swirl of movement and heroic modeling. But a closer inspection reveals it is a 1935 drawing by Paul Cadmus of an African American man tied to a horse, surrounded by grotesque faces, and the title is

To the Lynching!

What is a warhorse, anyway? It is something that can be ridden reliably into battles both literal and metaphorical. A concerto of Beethoven is a warhorse. But it is also an issue that will not go away, a flashpoint, a galled sore, a controversy, a steed to be ridden toward the Apocalypse. Like race, in America. Or sex. Or war.

Yusef Komunyakaa's war was in Vietnam. His 1988 book

Dien Cai Dau

(the title translates the Vietnamese for "crazy," as applied to the American soldiers) contains his widely anthologized poem "Facing It," which includes these lines: "I turn/ this way - the stone lets me go./ I turn that way - I'm inside/ the Vietnam Veterans Memorial/ again. . . . " The veteran confronting Maya Lin's memorial discovers that it both reflects and absorbs him.

Komunyakaa has made of his poetry a perfect vibrating membrane between the self and the world, between the present and the past. "You see these ears?" he writes. "They may detect a quiver/ in the grass, an octave/ higher or lower -/ a little different, an iota. . . . " He recently completed a verse play based on

The Epic of Gilgamesh

and its ancient meditation on death; and with a measured outrage, his new book explores the dismal through-line of war: " . . . we're near the Perfume River/ or outside Ramadi. You see,/ the maps & grids flow together/ till light equals darkness."

Indeed, the book constitutes a kind of atlas of slaughter, opening with that jawbone of an ass with which Samson slew the Philistines, and ranging through centuries of men carried to war on horseback or by horsepower: the famous clay army of the Emperor of Qin; Attila the Hun astride his spotted mare; the depredations of African tribes, selling each other into slavery; the cyclorama of Cossacks and Hussars; the screams of Guernica; Oliver the paratrooper, blown to pieces by a grenade in Vietnam; and the lie of the "surge" in Iraq. Komunyakaa writes: "Listen to the wind beg. Always more young, strong, healthy bodies. Always." Those he calls "the old masters of Shock & Awe" are eloquently rebuked here. Komunyakaa says he will tell the president "how the mouth entangles/ brain stem & genitalia."

Another famous war poem, this time by Randall Jarrell, likens a gunner killed in his bomber's ball turret in World War II to a child in the womb: "From my mother's sleep I fell into the State . . . " and Komunyakaa riffs on this, too, in a poem that imagines an American soldier in his armored vehicle entering Baghdad: "I was inside a womb,/ a carmine world, caught in a limbo,/ my finger on the trigger, getting ready to die,/ getting ready to be born."

The other "warhorse" that makes the membrane of poetry vibrate, for Komunyakaa, is sex, which is, after all, close to death. The book's opening section is a cycle of sonnets called "Love in the Time of War," and in the first poem "The warrior-king summons one goddess/ after another to his bloodstained pallet." Does the warrior-king do this to devirginate each goddess? Or to seek some balm for his mortal wound? Love seems inseparable from war for Komunyakaa. And the book is likewise informed throughout by the subtle social outrage of separate-and-unequal: "I know men/ who did more than I dreamt,/ & only received a smudge of blood/ on bronze because of black/ or brown skin, shortchanged by a pen."

The last part of

Warhorses

is a long poem ingeniously titled "Autobiography of My Alter Ego," crafted out of matching half-lines like a call-and-response. The life described is both the poet's and not the poet's. A grandfather tells the poem's speaker, "Boy, you/ were born one hundred steps/ ahead of many. You/ inherited the benefit of a doubt." As a poet of supreme sensitivity - that vibrating membrane - it has been Komunyakaa's fate to experience the extreme violence of race, of war, and of love, and to survive them all, heavy with the measure of those who are dead, making songs that are potent and comprehensive. In the anguish of living on the threshold lies his honesty, asking "Questions/ I didn't know I had - / as if I had stopped/ at the bloody breach - / the stopgap between/ animal & human being."