Novel set in Alaska has characters teetering on the edge

Quick: make a list of novels set in Alaska. After Jack London's The Call of the Wild (1903), does anything come to mind? If you are a fan of Michael Chabon, you might remember that his strange novel of alternative history from 2007, The Yiddish Policemen's Union, was set in an imagined Jewish settlement at Sitka, Alaska, but after that, you would be hard-pressed to come up with much.

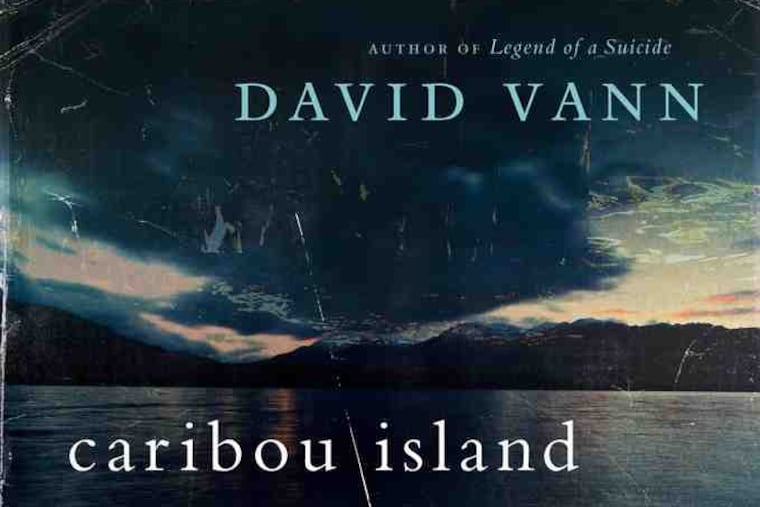

By David Vann

Harper. 304 pp $25.99

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by Kevin Grauke

Quick: make a list of novels set in Alaska.

After Jack London's The Call of the Wild (1903), does anything come to mind? If you are a fan of Michael Chabon, you might remember that his strange novel of alternative history from 2007, The Yiddish Policemen's Union, was set in an imagined Jewish settlement at Sitka, Alaska, but after that, you would be hard-pressed to come up with much.

Enter David Vann. Born and raised on Adak Island, Alaska, Vann has written two works set in the forty-ninth state - 2008's collection of short fiction, Legend of a Suicide, and now Caribou Island, his first novel. His first work, winner of the prestigious Grace Paley Prize, consisted of five linked stories and a novella (the book's masterful centerpiece, "Sukkwan Island") that chronicled a son's struggle to come to terms with his father's suicide. Both brutal and beautiful in its emotional intensity, it marked Vann as a writer whose next work one would eagerly await.

And here it is. And like Legend of a Suicide, Caribou Island involves the survivor of a parent's suicide. At the age of 10, Irene came home from school to find her mother hanging from the rafters. Now she is the mother of two adult children, and very unhappily married to their father, Gary, who wants to move from the banks of Skilak Lake on the Kenai Peninsula to Caribou Island, where he is building a cabin from scratch, using "no plans, no experience, no permits, no advice welcome." Despite opposing this (ad)venture, Irene assists him in his misguided scheme, primarily because she believes that Gary intends to leave her if - or, more accurately, when - this project fails, and she fears being abandoned again more than anything, even if the one abandoning her is a man who she is convinced has never loved her.

Although Irene and Gary's struggles with both the construction of the cabin and the destruction of their marriage lie at the heart of the novel, Vann integrates a number of other characters and perspectives.

Sometimes, we see the world - and the world here is nothing beyond the vast and desolate landscape of Alaska - from the point of view of Irene and Gary's children, Rhoda and Mark, among a number of others, including their respective partners.

While these other characters occasionally distract us with their anxieties and infidelities, their presence seems primarily meant to keep us from collapsing beneath the suffocating pressure building up between Irene and Gary, especially since several of the characters fade away unceremoniously by the last quarter of the novel.

Throughout, however, Alaska wields its implacable influence - sometimes as a storming, natural force, other times as an idea or symbol. Thirty years earlier, Gary convinced Irene to leave California in order to "go to the frontier, to soak up the wilderness."

From afar, Alaska is seductive; it promises escape and self-discovery. It rarely delivers, however, as Vann's characters discover. Immersed in its bleak isolation, they come to realize that it resembles a land of intriguing possibility less than it does "the end of the world, a place of exile." And as one character observes, "Those who couldn't fit anywhere else came here, and if they couldn't cling to anything here, they just fell off the edge."

When Caribou Island first introduces us to Gary and Irene, they are already dangerously close to falling off this edge, and it is a testament to David Vann's bravery as a writer that he refuses to look away from their inexorable movement toward it. For Gary, the "real Alaska didn't seem to exist." More accurately, the Alaska that he hoped to find, the mythical Alaska, is nowhere to be found. His last hope to find it is on Caribou Island, a wilderness within a wilderness - or a good place if "you wanted to be a fool and test the limits of how bad things could get," as one character observes.

To note that it does get bad is to give nothing away; trouble, if not disaster, seems likely from the novel's first dark page. To see how things deteriorate is, in part, what keeps us reading, but mostly we stay on Skilak Lake because we have no other choice.

Vann forces us to watch, to pay attention. He refuses to provide his characters - or us - with an easy, happy resolution. Instead, he gives us something much more valuable: an unflinching portrait of what can happen to lives when hopes and ambitions wander off, get lost, and surrender to the merciless cold.