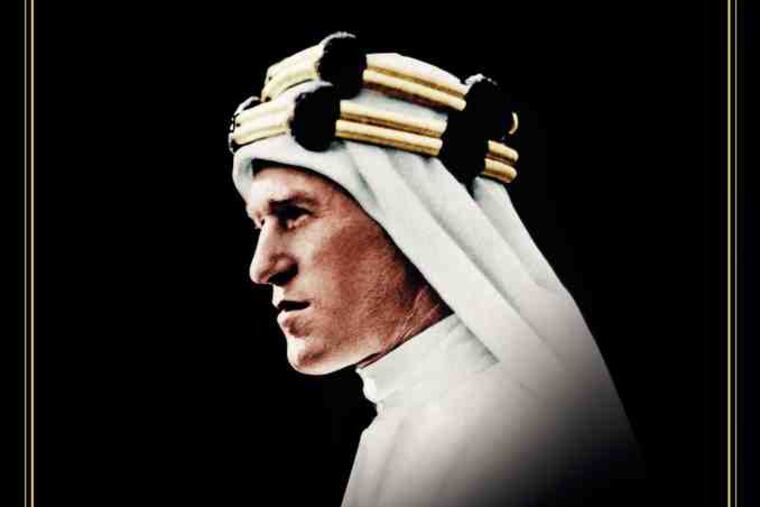

Biography of the brilliant, conflicted 'Lawrence of Arabia'

T.E. Lawrence, "Lawrence of Arabia," was one of those rare individuals to whom the gods grant great gifts: superior intelligence, uncommon courage, military genius, and literary skill. But those traits denied him the one thing he longed for - contentment.

The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia

By Michael Korda

Harper. 784 pp. $36

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by John Rossi

T.E. Lawrence, "Lawrence of Arabia," was one of those rare individuals to whom the gods grant great gifts: superior intelligence, uncommon courage, military genius, and literary skill. But those traits denied him the one thing he longed for - contentment.

Michael Korda's new biography outstrips the more than 100 previous attempts to tell the fascinating, almost unbelievable tale of the man who became a legend in his own lifetime. Korda, most recently author of the best biography of Dwight D. Eisenhower, outdoes himself with Hero.

Lawrence's story is well-known to many through the film Lawrence of Arabia and the powerful performance of Peter O'Toole. Korda goes well beyond the movie.

Lawrence was the illegitimate son of an English minor aristocrat. A brilliant student with a gift for languages - he spoke French at 6 and began studying Latin at 5 - Lawrence studied at Oxford and was in the Middle East doing archaeological work when World War I broke out.

Korda traces the story of how Lawrence, 5-foot-5 and just 112 pounds, at 29 gained the confidence of the Bedouin Arab tribes and led them in a guerrilla campaign that harassed Turkish forces from the Arabian Peninsula to Syria. In the process, Korda points out that Lawrence developed many of the modern techniques used by subsequent guerrilla leaders - hit-and-run raids, low casualties, always unorthodox tactics.

In a war that bestowed glory on few, Lawrence became famous for his bravery and military brilliance - Korda even compares him to the young Napoleon. But Lawrence came to believe that he had failed the Arabs by not gaining a homeland for them. He rejected the celebrity status he achieved for his exploits. This was especially so when the American journalist Lowell Thomas, one of the most gifted and unscrupulous promoters, turned Lawrence into a celebrated hero - in Thomas' hype "the Prince of Mecca" or even worse, "The Uncrowned King of Arabia."

Lawrence came to reject his role as "hero," but in running away from it only attracted more attention to himself. Korda compares Lawrence to Princess Diana as a master at "the art of seeking to avoid the limelight while actually backing into it." Lawrence tired of his fame and sought isolation, if not annihilation. He took up riding a powerful motorcycle at high speed, acting at times as if he wanted to kill himself.

At the same time, Lawrence sought to tell the story of the Arab revolt to a wide audience, to show them how the Arabs had been betrayed by Great Britain and its Allies. His masterpiece, The Seven Pillars of Wisdom, and its abridgment, The Revolt in the Desert, carried his fame to higher levels. As a celebrated editor in his own right, Korda is excellent on the details of how Lawrence wanted the books published. He preferred only very expensive editions of The Seven Pillars of Wisdom and a popular version of its abridgment. He was successful, and both books became best sellers. Typically, Lawrence rejected all royalties, instead giving the money to charity.

The last five chapters of Korda's book focus on Lawrence's desperate struggle to find a place for himself, a struggle that was never fully successful. He first enlisted in the Royal Air Force under an assumed name, Ross, and when found out, joined the army, also using a pseudonym, this time Shaw. When he was discovered, he returned to the air force, where he spent the last years of his life.

For someone who sought the role of the recluse, Lawrence had a positive genius for making lasting friendships. One of his closest relationships in the last years of his life was with the playwright George Bernard Shaw and Shaw's wife. Shaw guided Lawrence through many of the difficulties in writing The Seven Pillars of Wisdom. He also based the character St. Joan in his play of the same name on Lawrence. Shaw's wife, Charlotte, became a substitute for the mother that Lawrence never felt close to. To her he wrote some of his most revealing letters, including the details of his rape by the Turks during the war.

The rape was at the root of many of the problems that Lawrence confronted after the war. Korda argues that he suffered from a form of post-traumatic shock, which was unrecognized at the time. One way Lawrence sought to deal with his sense of unworthiness was to hire someone to beat him. He felt that he had not sufficiently resisted his abasement by his Turkish captors and, what is worse, had enjoyed the experience.

Lawrence was a confused and conflicted individual. Despite enjoying his last years in the RAF, where he became a skilled machinist, Lawrence never found the contentment he sought.

He died in a motorcycle accident in March 1935, swerving to avoid two young bicyclists. Had he lived, he might have found a role that suited his talents in World War II. His close friend, Winston Churchill, would have used his unorthodox skills.

Lawrence's death at 50 assured his apotheosis, similar to that of A.E. Houseman's athlete dying young:

Now you will not swell the rout

Of lads that wore their honours out,

Runners whom renown outran,

And the name died before the man.