Argentina's 'Dirty War' recounted in a debut novel

Edgardo David Holzman's debut novel, Malena (Nortia Press), opens in a smoky Buenos Aires cafe. A dashing army captain named Diego and his lover Inés are dancing to their favorite tango, "Malena."

Edgardo David Holzman's debut novel, Malena (Nortia Press), opens in a smoky Buenos Aires cafe. A dashing army captain named Diego and his lover Inés are dancing to their favorite tango, "Malena."

Malena sings the tango like no one else

and into each verse she pours her heart.

Her voice is perfumed with the weeds of the slum.

Malena feels the pain of the bandoneón.

It's an intensely romantic scene - but it's also a scene filled with mortal dread.

We're not in Buenos Aires now but in 1979, when the famed cosmopolis served as the nerve center of one of the most brutal dictatorships the West has ever seen.

Three years earlier, a coup d'etat had brought into power a military junta under Jorge Rafael Videla. For nearly eight years, the junta carried out a meticulously planned and executed program of state terrorism known as the "Dirty War," which, according to internal estimates, led to the kidnapping, torture, or execution of nearly 30,000 Argentinians, most of them innocent civilians, at more than 340 concentration camps located throughout the country.

This horrific world is the setting of Holzman's arresting, moving, and disturbing thriller about three friends who try to survive the brutality around them and eventually escape it.

Inés, an innocent, is unaware of the depth of darkness unleashed by Argentina's government, while the army captain is at its heart.

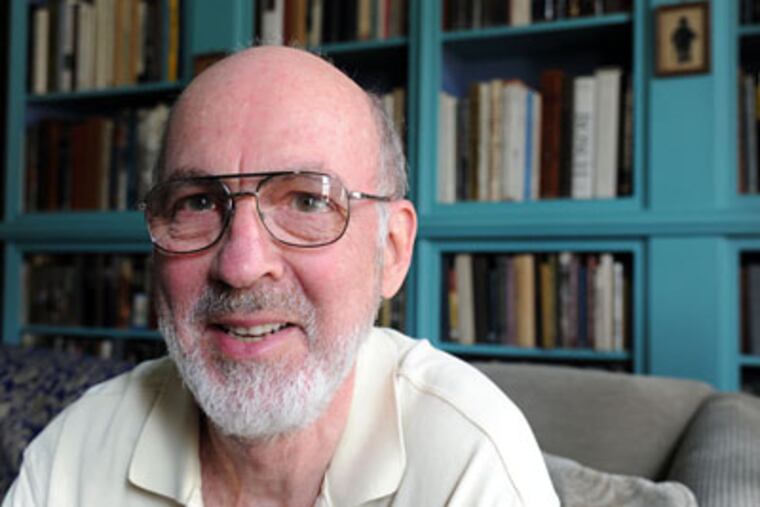

"Diego is sort of an unwilling spectator and always has participated only on the fringes of what is going on," Holzman, an Argentine-born, Philadelphia-based civil rights lawyer and legal translator, said in a recent interview.

He becomes desperate to escape when his superior, Col. Indart, orders him to join one of the death squads. In a brilliant ploy, the security forces made it mandatory for all soldiers to do a tour with the death squads, Holzman explained. "That way everyone would have to get their hands bloodied and no one could claim he was innocent."

The third protagonist, Kevin "Solo" Solorzano, is an Argentinian American who comes to Buenos Aires as part of a human rights commission - and to smuggle out his former lover, Inés.

Holzman said he wrote Malena as a way to bring the Dirty War and its lessons to the attention of the general reader.

"Many people know about [Augusto] Pinochet in Chile," he said, referring to the dictator whose infamous policy of "disappearing" dissidents has been told in a number of books and movies, including Costa-Gavras' 1982 hit Missing, which starred Jack Lemmon and Sissy Spacek.

"Things were far worse in Argentina," said Holzman. "With Chile, we're talking about maybe 3,000 dead. In Argentina we're talking 30,000."

Holzman, 65, said Chile was one of many Latin American nations that were in the grip of right-wing dictatorships during the era, including Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Paraguay, and Uruguay. Many of them received financial and military support from the United States.

"It's a story that's hardly known in this country, except for people who have studied Latin American history," Holzman said during a recent visit to his striking Frank Furness-designed house in Center City.

Although he was born in Argentina, Holzman spent most of his childhood following his father, a journalist and diplomat, around the world.

After earning a law degree in Argentina, he moved to Washington to take an advanced degree in international comparative law at George Washington University.

His involvement with the human rights movement began in 1974 when he was sent to Chile as an interpreter for a human rights commission assembled by the Organization of American States.

"I was a part of a team of lawyers who went down there to investigate human rights violations," said Holzman. "It was a year after Pinochet took over and already there were reports of tortures and killings so massive, there was no way for the government to hide it."

Holzman said the idea for his novel began germinating in Chile.

"Most of all, this experience opened my eyes to the huge gap between the official government narrative and what was actually going on."

The translator said he was especially moved when hundreds of people lined up outside the investigators' hotel seeking help: "It was this block-long line of men and women looking for the disappeared."

During a spell with the International Monetary Fund, Holzman had a glimpse of the other side, of how repressive governments spun their stories, when he was asked in 1981 to act as intepreter and escort to a compatriot - Argentina's President Roberto Viola - during a state visit to Washington.

Holzman shadowed the dictator as he was grilled by Congress about Argentina's human rights record.

It wasn't until 1984, when Argentina's newly elected civilian government released a human rights report, that the extent of the junta's reign of terror was revealed. The truth commission's findings continue to lead to prosecutions today.

Holzman said he closely studied the report, titled "Never Again," and constructed Malena using actual cases.

He said he was especially disturbed by the active role that elements of the Catholic Church played in the repression.

Before each flight, priests would bless the "death planes" from which prisoners would be pushed, often alive, into the Atlantic. Some heard confessions of prisoners, then turned over the information to the interrogators, Holzman said.

"This is still a very controversial issue and a very painful one for a lot of Catholics in Argenina," he said. "The church leadership and the Vatican were silent then and they still are today."

Holzman said he is proud that the truth commission has become a paradigm for the human rights movement and inspired numerous such initiatives, including South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and led to the birth of the modern human rights movement.

After so much darkness, he said, some light finally is coming through.