The upper-case life of a lower-case poet

On Sept. 2, 1962, Edward Estlin Cummings suffered a stroke at Joy Farm in Silver Lake, N.H. He never regained consciousness and died the next morning. He was 67.

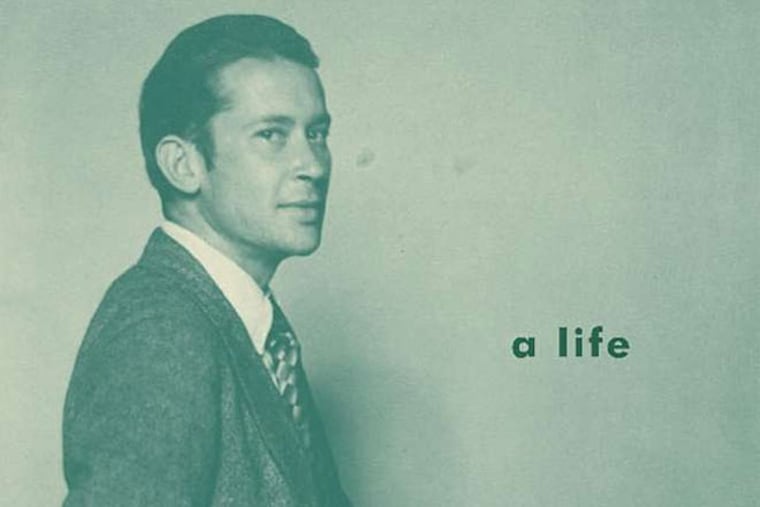

e.e. cummings

A life

By Susan Cheever

Pantheon. 213 pp. $26.95

nolead ends nolead begins

Reviewed by Frank Wilson

On Sept. 2, 1962, Edward Estlin Cummings suffered a stroke at Joy Farm in Silver Lake, N.H. He never regained consciousness and died the next morning. He was 67.

If he ever thought of death while at the farm he and his younger sister Elizabeth had inherited, it was probably of one that had happened there during a summer stay 51 years earlier. Cummings and Elizabeth had ventured out on the lake "to try out one of their father's latest acquisitions - a supposedly unsinkable canoe." They brought along Cummings' faithful dog, Rex, who, when they were well offshore, snapped at a hornet and capsized the boat. The dog at first headed for shore, then came back, then panicked and tried to save himself by climbing onto Elizabeth. To save his sister, Cummings had to drown Rex.

"Estlin Cummings never had another dog," Susan Cheever writes in this exquisite biography of the poet with the trademark lower-case moniker. (He was always called by his middle name, Estlin. Edward was his father's name.)

Cheever provides sound evidence that there was a good deal more behind the lowercase than whimsy:

Cummings was smaller than his father, who was definitely an Important, Imposing capital letter. By using the lowercase i he was able to rebel, break the rules, adopt the Yankee humility of someone his family depended on, and present himself as playful rather than pompous.

Cummings was a friend of John Cheever, Susan Cheever's father, and Susan Cheever begins her book with an account of the evening her father drove her and Cummings to her high school, where Cummings was scheduled to read. The poet seems to have made an indelible impression that informs this lean and insightful story of his life. This is biography as portraiture, evoking a complex personality - electric, irascible, truculent, and passionate - that serves as the lens through which we see the circumstances and events. Complementing that is Cheever's own standpoint, a shrewdly perceptive mix of honesty and affection.

Cummings was born into privilege in Cambridge, Mass., in 1894. His father was a prominent clergyman, and Cummings grew up within walking distance of Harvard University, which he entered at 16. He enjoyed early success, and ended up making a decent living reading his poems. After two brief, failed marriages, he spent the last 28 years of his life with Marian Morehouse, 12 years younger, a few inches taller, and the first supermodel.

In between, though, his book Eimi, a most unflattering - that is, accurate - account of a visit to Stalin's Russia, alienated his friends on the left and left him for a time without a publisher. His father was killed when the car his mother was driving on the way to Joy Farm was struck by a train. Edward Cummings died instantly. His wife suffered mostly bruises. Most years, the poet got by mostly on a grant here, an advance there, and the generosity of his mother and his friends.

And then there was his daughter.

Cummings' first wife, Elaine, had been the wife of his best friend and patron, Scofield Thayer, one of the two men behind the famed Dial literary magazine. Cummings and Elaine had an affair while she was still married to Thayer. In fact, the girl she gave birth to during that marriage was Cummings', not Thayer's, though Thayer adopted her. Cummings and Elaine were married for less than year when she told him she was in love with another man whom she intended to marry.

Cummings loved his daughter - named Nancy, though Cummings always called her Mopsy. But he saw her only infrequently, and she was always chaperoned. Then Elaine and her new husband, an Irish banker, moved to Ireland: "Nancy was not told until many years later that E.E. Cummings was her father . . . . She didn't see him again for twenty-two years."

The story of how Nancy learned that Cummings was her father is too unusual to give away in a review.

As a poet, Cummings early hit upon a style and method that he made a career of refining. Cheever doesn't spend undue time analyzing the work. She tends to quote whole poems, not scrutinize lines. She harbors no doubts about Cummings' significance. On the first page of the book she calls him "this country's only true modernist poet," and on the last page, "one of the great and most important American poets." She also points out that he was the only one who really was classically trained: "His high jinks with poetic forms are based on a knowledge of those forms - in English, Latin, and Greek. . . . His understanding of the history of poesy, scansion, meters, rhyme schemes, forms, and techniques . . . is what allowed him the experiments." Those experiments may seem "spontaneous and young," but they were "studied, written, and rewritten, and based on what had gone before."

Judged by the evidence Cheever submits, Estlin Cummings was definitely an upper-case poet.