Excellent points, but no hard questions

Don Argott's pugnacious documentary The Art of the Steal chronicles the utopian past and the pragmatic future of the Barnes Foundation.

Don Argott's pugnacious documentary The Art of the Steal chronicles the utopian past and the pragmatic future of the Barnes Foundation.

The repository, which includes 181 Renoirs, 69 Cezannes, and 60 Matisses, has been the subject of epic legal challenges. Most recently, a petition opposed a judge's ruling that three foundations could relocate the school from Merion's leafy Latches Lane to Philadelphia's museum mile on the Ben Franklin Parkway.

As a movie, Steal is as finely wrought as the decorative ironworks that hang on the walls of the Barnes between Picassos and Seurats. Yet as a narrative of the facts, it is as one-sided as a plaintiff's brief.

Argott simplifies the institution's convoluted, colorful history into stark black and white, smearing villains and cheering heroes. As he tells it, the Barnes is an orphan in Philadelphia's most infamous custody battle.

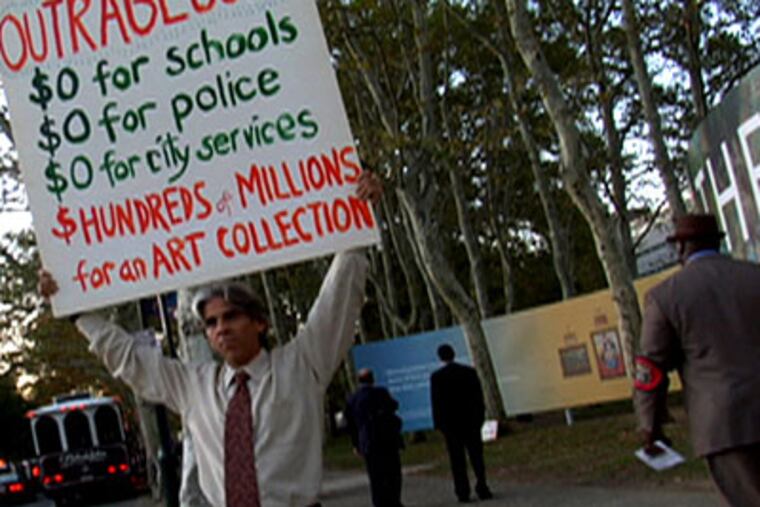

The bad guys are a shadowy "cabal" of Philadelphia foundations (Annenberg, Pew, Lenfest) conspiring to break Barnes' will and abduct his babies in order to exploit them purely for touristic purposes. The good guys are the Friends of the Barnes, a group that seeks to preserve the collector's babies as he intended, in the villa especially built for them.

One would not know from the movie that the so-called bad guys' plan would keep the foundation's holdings intact, maintain its educational mission, and bring Barnes' underknown collection to a greater number of people. (Suspicious of Argott's agenda, the "baddies" declined to present their case; Lenny Feinberg, the film's executive producer, is a Barnes alum who opposes the move.)

Steal's so-called good guys - Barnes chronicler John Anderson, NAACP chair Julian Bond, and L.A. Times art critic Christopher Knight - have many excellent points, and they make them passionately, heatedly, and repeatedly.

Instead of asking hard questions, Argott's film poses a rhetorical: "Isn't it awful that this jaw-dropping collection will be moved from its jewel box in Merion?" And to this, anyone who has experienced the Barnes - with its sublime juxtapositions of masterworks and commonplace objects - has to answer, yes, awful.

But the second time Drexel professor Robert Zaller, a Friend of the Barnes, is heard insisting that the proposed move downtown is "the greatest act of cultural vandalism since World War II," you think: Really?

Then the hard question emerges, not from the screen, but in the viewer's mind: Does moving this chronically underfunded collection from its suburban enclave, where there is limited visitor access, to an urban center where it will have a solid endowment and greater public access, constitute vandalism? This viewer answers no: not vandalism. Pragmatism, perhaps, but not vandalism.

Rather than tell the whole story of how the Barnes move came about - a Dickensian saga of bad financial planning, worse management, endless lawsuits, and meddling NIMBYs - Argott's talking heads spin a unified conspiracy theory of how Philadelphia money and institutions always had it in for Barnes.

This is a debatable point. Still, Steal does mention that Dr. Albert C. Barnes had it in for Philadelphia institutions, most notably the Museum of Art, which he described as "a house of artistic and intellectual prostitution."

"Barnes had a litigious soul," Anderson wrote in his book Art Held Hostage, adding that the foundation "is built on litigation."

Little wonder that the testament of the man who wanted his collection to be open to the public, but also wanted to handpick those he admitted, has proved so damned hard to interpret.

The film's recurring visual motif - a marker striking out clauses of Barnes' will, officially called an "indenture" - is underscored by ominous Philip Glass music. The assumption is that a will is sacrosanct. In fact, Barnes' indenture has an escape clause, in Section 11 of Article 9, allowing, should circumstances warrant, deviation from his wishes.

It would have been helpful to know whether institutions comparable to the Barnes - such as the Isabella Stewart Gardner in Boston, or the Frick in New York - had departed from their founders' original intentions in order to preserve the establishments. It would also have made for a stronger film had the Friends of the Barnes disclosed its proposed business plan to keep the collection in Merion.

Many of the talking heads argue that if the foundations could raise money to move the Barnes, why couldn't they raise money to keep it in Merion? One possible answer: The foundations and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, which appropriated $107 million for the move, didn't think the Barnes was viable in Merion, where restrictions on attendance limited ticket revenue.

Credit Argott (who previously made the documentary Rock School) for attempting to cut this Gordian knot. But lament that in his attempt, the filmmaker unintentionally tightens it.

There is another unintended consequence of Art of the Steal. The brief glimpses of Cezanne's Card Players, Matisse's Joy of Life, and Seurat's Models make you want to see these masterworks no matter where they are located, undermining the film's premise that they should be enjoyed only in Merion.EndText