Museum's golden girl back at the top

After more than a year of radiographic and electron microscope analyses, acid washes, hand filing and scraping, heating, archival research, fussiness, and hand wringing, the Philadelphia Museum of Art has at last unveiled its newly resplendent statue Diana.

After more than a year of radiographic and electron microscope analyses, acid washes, hand filing and scraping, heating, archival research, fussiness, and hand wringing, the Philadelphia Museum of Art has at last unveiled its newly resplendent statue Diana.

She again looks out over the Great Stair Hall, seen as she has never been seen before in Philadelphia - or anywhere else, for that matter.

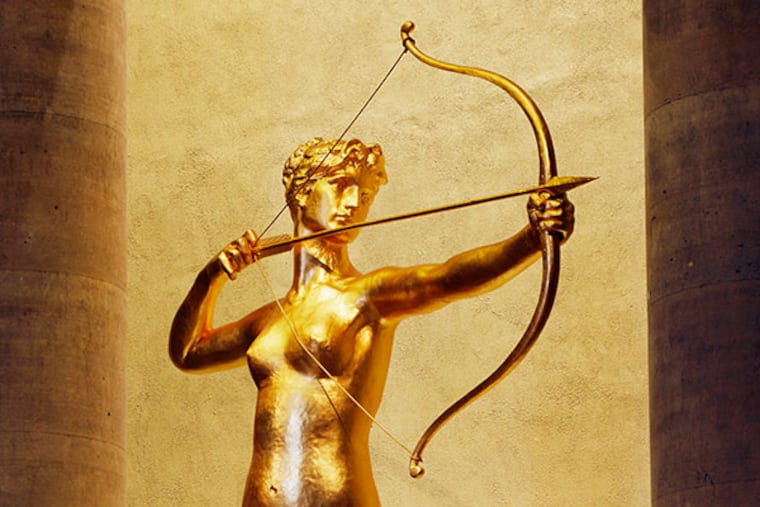

Dressed now in a cloak of deliberately muted gilt, the goddess of the hunt glows atop the staircase, set in an alcove washed with new lighting, golden as the sunlight that flooded the soaring hall Thursday morning.

"She didn't always look like this, although initially she did," said Timothy Rub, museum director, at the unveiling of the restored sculpture. "Just a few years ago we decided we wanted to restore her to what she initially looked like."

But in fact, Diana never did look quite like this.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens created the now-iconic sculpture in 1892-93 to serve as a monumental weather vane atop his friend Stanford White's newly constructed Madison Square Garden in Manhattan. Rising 347 feet into the air, she was gilded then, too - shiny and gleaming, a bank of spotlights drenching her gold surfaces, transforming a weather vane into a beacon for New York City.

But in 1925, the old Garden was demolished, and Diana was placed in storage until Fiske Kimball, then the dynamic young director of Philadelphia's art museum, in 1932 persuaded the New York Life Insurance Co., Diana's owner, to give her to the museum.

At that point, after more than a quarter-century in the New York sky, Diana's bright gilding had largely worn away, and her copper body had corroded to a dark green. She was washed and surfaces were repaired, but when she was installed during the Great Depression at the top of the stairwell, the museum did not have funds to attempt a regilding.

For 80 years, bow in hand, the 13-foot high Diana remained in place, giltless, until Bank of America granted the museum $200,000 last year to once again shower her in gold.

Translating that intent into fact proved an extremely difficult process, according to museum conservator Andrew Lins. There was uncertainty about how the sculpture was put together and how the armature within its hollow interior served as support.

A borescope was employed to peer inside the sculpture, said Lins. Radiography determined the thickness of its copper sheeting (more than 70 pieces of copper are riveted and soldered together to form Diana's body). An acid wash was used to clean the surface.

A scanning electron microscope was used to analyze minute samples of the original gilt on her body. This last bit of technical wizardry proved particularly important, Lins and other museum officials said.

Because the newly gilded Diana would be seen indoors and more or less at eye level - not more than 300 feet above the street, as she had been in New York - a bright gilt coating could prove overwhelming and detract from the sculpture's subtle modeling.

So Lins and Kathleen A. Foster, curator of American art, wanted to know exactly what the chemical composition of the original gilt might be. And Foster was particularly focused on discovering what kind of gilding the famously fussy Saint-Gaudens used on works designed to be seen close up.

"Gold comes in a whole range of spectrums," Foster said. "Just like no white is white. There's a range."

Gold leaf with the same chemical composition as the original was applied to Diana, and a painstaking process of muting commenced.

"We wanted to try to understand what Saint-Gaudens wanted to do," Foster said. The artist was "quite finicky" about gilding, and "treated the final surface artistically." While she discovered that Saint-Gaudens had used pigment to modify his final surfaces, the museum chose a different route to mute Diana's super-shiny aura.

Lins said the sculpture has been sprayed with an application of gum arabic and fumed silica, which serves to reflect light at lateral angles.

Foster said the muted surface has a "pearling" quality to it.

Rub called the final result "a complete makeover."

Said Lins: "Diana glows rather than glares."

The museum has posted three short videos detailing the restoration of Diana. They can be found on the museum website at www.philamuseum.org/conservation/21.html.

215-854-5594

@SPSalisbury