Photographer focuses on country stars

Henry Horenstein grew up in the New England seaport town of New Bedford, Mass., so the geographical-determinist theory of musical taste makes it unlikely he'd become an ardent country music fan.

Henry Horenstein grew up in the New England seaport town of New Bedford, Mass., so the geographical-determinist theory of musical taste makes it unlikely he'd become an ardent country music fan.

Happily for the photographer, whose black-and-white shots of country and bluegrass stars such as Dolly Parton, Bill Monroe, and Loretta Lynn now hang on the walls at Center City's Gallery 339, in an exhibition called "Tales From the '70s: Honky Tonk & Speedway," it didn't work out that way.

"We were a much more rural country then," says Horenstein, 65, on the phone as he drives from his home in Boston to Providence, R.I., where he teaches photography at the Rhode Island School of Design. "More people lived in the country than in the cities. And the music is rural music. But mainly for me, I heard the music on the AM radio. Johnny Horton, Marty Robbins, Johnny Cash, they were my favorite singers. I loved that stuff."

Horenstein majored in history at the University of Chicago in the 1960s. He brought a camera along for a junior year abroad in England, where he studied under esteemed British historian E.P. Thompson at the University of Warwick.

Thompson, author of The Making of the English Working Class, "was a guy who believed in documenting the undocumented," Horenstein says. Another teacher, the photographer Harry Callahan, gave him another important lesson. "Harry told me to shoot what I love. To take pictures of what I was naturally drawn to."

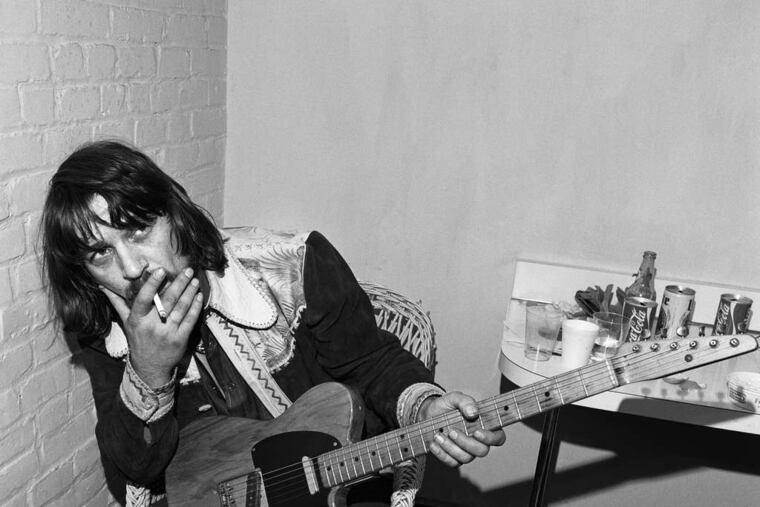

For Horenstein, that meant country music. The performers, such as Waylon Jennings and Jerry Lee Lewis and Emmylou Harris, are captured in revealing portraits in the Gallery 339 show and the accompanying book, Honky Tonk (W.W. Norton, $50), published in an updated edition in 2012. But it also meant the fans, and venues like Tootsie's Orchid Lounge and the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville, and the Lone Star Ranch in Reeds Ferry, N.H.

"I liked the places, I liked the joints," he says. "I liked to drink beer. And I liked the whole casualness of it."

In Chicago, he'd met fellow music lovers who would found Boston-area record labels like Rounder and Flying Fish, and he got some work shooting album covers.

Horenstein took his most famous picture for the alt-weekly Boston Phoenix. It shows a 26-year-old Dolly Parton, composed and radiant, backstage at Boston's Symphony Hall, where she was performing with the more flamboyantly dressed Porter Wagoner.

"I just remember I had the worst crush on her," Horenstein recalls, laughing. "Besides being very cute, she was charming. We all know that now but I didn't know it then. We were kind of the same age, so I could dream. But I was very shy. I only took a few pictures. I didn't know the way it worked, that performers were there to be photographed. I thought it was an imposition. But I got a couple of good pictures, and that's the one that survived."

Most of the pictures in Honky Tonk were not the result of assignments but grew out of Horenstein's hanging around musicians, earning their confidence. To make a living in the '70s, besides writing popular photography textbooks and taking pictures for projects like the Connecticut drag strip series "Speedway" (also part of the exhibition), "I did everything," Horenstein says. "I painted houses, sold blood. I took pictures for myself, occasionally for money."

"It's so different now," he says. In the '70s, "music was a much smaller business," and he could get intimate access. "There were a few big stars, like Johnny Cash. But there weren't that many. People were hustling to keep their thing going. If you went to the Grand Ole Opry, it wasn't that hard to get a pass, and then you could wander around backstage. And people would invite you to their homes if they thought it would help their careers."

Horenstein is a country traditionalist. To demonstrate his lack of knowledge of rock-and-roll, he says, "I've heard of David Bowie, but I couldn't recognize him in a million years, and I don't know what his music's like."

He's not one to dismiss contemporary country, though, or bang on about how great the old days were. "The usual line is 'The music sucks now.' But a lot of the music sucked then, to be honest. And there are a lot of good performers, good singers, around now. Jamey Johnson, he could stand with any of these guys. I saw Iris DeMent last week. She was amazing.

"The difference, I guess, between now and then is you knew what you were getting with those performers. They didn't have a lot of other people around them, putting the music over. They were who they were, for better or worse."

Horenstein has published more than 30 books, most of them photo collections that focus on a discrete subject, from horse racing to the nearly abstract pictures of animals in Animalia (2009) and neo-burlesque and drag shows in Show (2010).

He has kept shooting country, though. There are pictures in Honky Tonk, like the portrait of Asleep at the Wheel leader Ray Benson, who's from Springfield, Montgomery County, taken in 2011.

When he started shooting now-departed stars such as Waylon Jennings and Tammy Wynette and DeFord Bailey, who was the first African American member of the Opry, Horenstein says, he was "absolutely conscious" that he was recording history.

"That was exactly what I was trying to do," he says. "I had not had any art training, really. My training was in history. The other part I was uncertain about, but I was fairly overcertain about the history part - that these people needed to be documented. More than any project I've ever done, I did what I set out to do with 'Honky Tonk.' Maybe it was just because I was young and stupid. But I was pretty confident that what I was doing was important."