Crescendos in a classical year

The classical music year was all too interesting - in the Chinese-proverb sense of the word - with the Philadelphia Orchestra entering Chapter 11 bankruptcy and the Kimmel Center closing (if only momentarily) amid a union standoff.

The classical music year was all too interesting - in the Chinese-proverb sense of the word - with the Philadelphia Orchestra entering Chapter 11 bankruptcy and the Kimmel Center closing (if only momentarily) amid a union standoff.

Artistically, though, the community remained defiantly strong. In its European festivals tour, the Philadelphia Orchestra was playing for its life and, according to most of the critics, reestablished its lofty position in the global music community. Even if other Philadelphia musical institutions didn't have their future so directly on the line, this was not a time for backsliding or retreating into safety.

The peaks for me - among concerts, operas and recordings - are as follows.

American Sublime: The death of composer Morton Feldman in 1987 was barely felt. Now, Feldman is emerging among the most important American composers of the late 20th century. In what was one of the biggest Feldman festivals anywhere, ever, the Bower Bird-produced eight-day American Sublime left you aching for more, even after the six-hour String Quartet No. 2, a spacious, subtle meditation in sound at the Philadelphia Cathedral.

The Crossing: Audiences didn't see Latvian composer Eriks Esenvalds dashing into Chestnut Hill's Presbyterian Church, hours before the June premiere of his new piece Seneca's Zodiac, outfitting the piano strings with specially whittled pencil erasers he pulled from a Starbucks/Riga bag. But audiences heard one of many otherworldly effects in a universe of sounds depicting constellations falling from the sky, portrayed by choral exhalations and tuned water glasses.

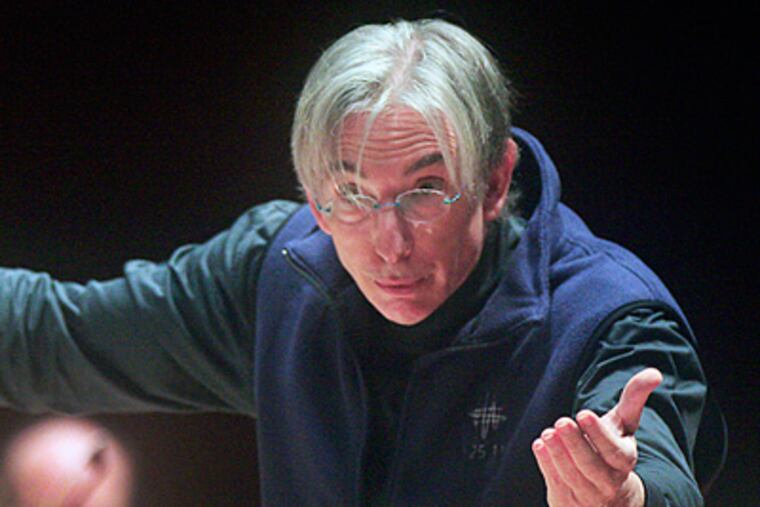

Philadelphia Orchestra: The first important night was the closing of the European tour in Paris. Chief conductor Charles Dutoit led Berlioz's Symphonie Fantastique with perfect order and complete madness running neck and neck. Then, in October, music director designate Yannick Nézet-Séguin conducted Brahms' A German Requiem with all the sureness that was lacking in his Mozart Requiem earlier in the year. The youthful voices of the Westminster Choir have rarely sounded so ethereal.

Joyce Di Donato: OK, I'm a sap. Her Philadelphia Chamber Music Society concert in March was wonderful by any measure. But in a career that has been full of false starts (such as her time at Philadelphia's Academy of Vocal Arts), Di Donato's return had special meaning, summed up in her choice of encore: "Over the Rainbow." A quiet wallop.

The Thomashefskys: Music and Memories of a Life in the Yiddish Theater, February at the Kimmel Center. Somebody needs to preserve this lost continent of American theater, and the San Francisco Symphony's music director, Michael Tilson Thomas, has done so with an obvious advantage. His grandparents were Boris and Bessie Thomashefsky, who codified the genre and rode it to the end of the line. With photos, slides, films, and singers Judy Blazer and Shuler Hensley, Tilson Thomas created a picaresque tapestry full of infectious music and unforgettable characters.

Tempesta di Mare celebrated its 10th anniversary in October with an infrequent foray into the French baroque, a suite drawn from Rameau's little-known Les Fetes de Polymnie. It's a major discovery. with bursts of color and harmonic adventures everywhere.

Wanamaker organ's 100th anniversary: Admirers of this gargantuan instrument at Macy's no doubt consider its refurbishment an event unto itself. The bigger story is how its concerts promote repertoire from the instrument's 1920s heyday. Names like Charles Widor and especially Joseph Jongen don't turn up in mainstream classical concerts, but constitute a distinctive, overlooked musical corner that could refresh the usual redundant symphonic programs.

Capilla Flamenca and Piffaro: Only occasionally does Philadelphia hear the kind of early-music vocal groups that are everywhere in Belgium and Holland. One of the most distinctive, Capilla Flamenca, collaborated with Piffaro in May in a program of music by Heinrich Isaac - great music that seems that way only when sung at this level.

"Don Giovanni" at La Scala: Beamed live all over the world (including the Ambler Theater), Wednesday's opening night of the La Scala season wasn't just musically superb, with a cast featuring Peter Mattei and Anna Netrebko, but also had a provocative Robert Carsen production that explains the character's comings and goings ingeniously. Then, having descended to hell, Mozart's title character wins. (Yes, wins.)

The Smile Sessions: The Beach Boys? On a classical music list? This long-shelved late-1960s album - not to be confused with the version Brian Wilson finished several years ago - was long known mostly by "Good Vibrations" and "Heroes & Villains" that expanded pop song form into miniature suites. Similar feats by the Beatles and Jethro Tull led me to the longer forms of symphonic classical music. Now, with the original Smile album assembled from the original tapes, one hears even greater ambitions. Had it come out 40 years ago, might I have discovered Gustav Mahler sooner?