Kahlo’s suffering: Medical care didn’t help

The painter transformed her suffering into art. What caused her agony - and what does it say about medicine then, and today?

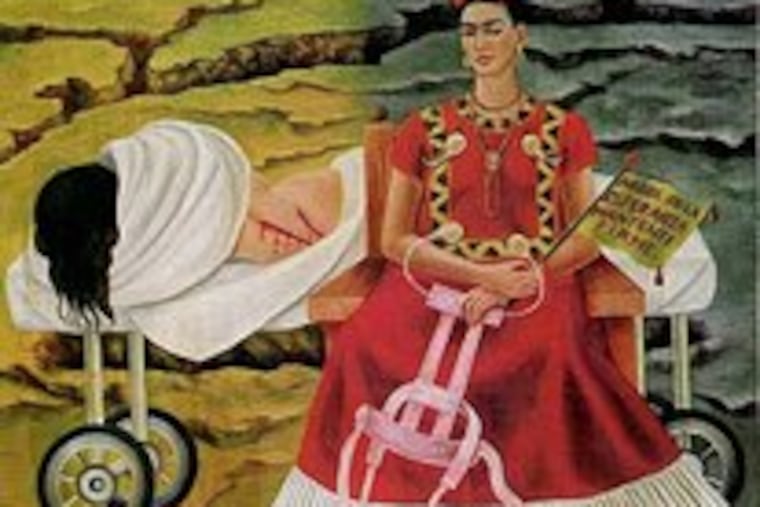

Frida Kahlo's physical and emotional suffering is as famous as the paintings in which she graphically deconstructed it.

Yet it remains a subject of speculation and reinterpretation more than half a century after the Mexican Modernist's death at age 47. The mythic quality of her agonies is part of the allure of exhibits like the one now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Parts of Kahlo's medical history will always be puzzling, but one thing is clear: She survived a horrific streetcar accident in 1925, a time when even the best hospitals in the world - and she certainly wasn't in one - could offer trauma victims little more than morphine. Blood transfusions, antibiotics, mechanical ventilation, anticoagulants, and modern orthopedic surgery - not to mention the science of physical rehabilitation - were years or decades away.

"To survive this in 1925 was close to a miracle, even at age 18," said Robert Ostrum, a Cooper University Hospital orthopedic trauma surgeon who treated New Jersey Gov. Corzine after his car crash. "If she had been 50 or 60, it would have been a death sentence."

Kahlo's unconventional unibrowed beauty, her exuberance, her tumultuous marriage (twice) to the philandering Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, and her friendships (some of them intimate) with cognoscenti ranging from Leon Trotsky to Henry Ford, are well documented. Photographs, correspondence, news coverage of the time, and the diary she wrote in her last decade of life, all attest to her larger-than-life life.

However, few of Kahlo's original medical records survived her. Most of what is known about her physical ills comes from the recollections of her contemporaries, or from a source sometimes given to hyperbole - Kahlo herself.

"She was one of the creators of her own legendary status," art critic Hayden Herrera wrote in her acclaimed 1983 biography, Frida.

Herrera, an organizer of the exhibit in Philadelphia, researched Kahlo in the 1970s. Even back then - before Fridamania turned the artist into an icon - her diagnoses, treatments and torments were sketchy.

"There's so much conflicting information," Herrera said by phone last week from her New York City home.

For example, Kahlo's classmates mocked her as "peg-leg" because her right leg was thinner and shorter than the other. Most biographers, including Herrera, attribute this to a bout with polio when Kahlo was 6 years old.

But Herrera added a footnote: In 1946, Kahlo recounted her medical odyssey to her gynecologist. Kahlo said she was healthy until 1918 - which would make her 11, not 6 - when she "had an accident and hit her right foot against a tree stump."

"This caused a slight deformation of her foot, which turned outward," the footnote continues. "Several doctors diagnosed the problem as polio. Others said Frida had a 'white tumor.' The treatment consisted of sunbaths and calcium baths."

Experts have speculated Kahlo actually had scoliosis (curvature of the spine) or malformed lumbar vertebrae due to a mild form of the congenital defect spina bifida.

What is undisputed is that she already had orthopedic problems on Sept. 17, 1925, the day a trolley rammed into the crowded bus she was riding.

Several people died at the scene. Kahlo's bloodied body was extricated from the wreckage by her then-boyfriend, who was horrified to discover a metal handrail sticking out of her abdomen.

The bar was pulled out, and Kahlo was rushed by ambulance to the nearby Red Cross Hospital - a former convent. She was found to have a broken collarbone, two broken ribs, numerous fractures of her already-bad right leg and foot, three fractured lumbar vertebrae, and pelvic fractures.

Remarkably, the handrail apparently did not rupture her abdominal or pelvic organs. (Kahlo's claim that the metal rod protruded through her vagina may be apocryphal.)

In any case, the severity of her trauma was on a par with Corzine's. He crashed at high speed, without a seatbelt, last April. He broke his collarbone, sternum (breastbone), 11 ribs, a lumbar vertebra, and his left femur (upper leg bone). The smashed femur ripped through the muscle and skin of his thigh.

Both Kahlo and Corzine had open, dirtied wounds that set them up for infection. Both had catastrophic blood loss from fractures of big, heavily vascularized bones - Corzine's femur and Kahlo's pelvis.

But that's where the comparison ends; their treatments were the difference between modern critical care and crossing your fingers.

Corzine was put on a ventilator, given seven pints of blood (the adult body holds 10 pints), and had a metal rod surgically implanted in his femur to stabilize the fracture. He received intravenous antibiotics, an anticoagulant, and a host of other medications, tests and monitoring.

Kahlo was basically cleaned up and encased in a plaster cast that kept her flat on her back.

Ostrum, Corzine's surgeon, said, "Today, there's a 10 percent mortality rate with pelvic fracture, but now we have ways to stop the bleeding without even going into the body. In 1925, blood transfusions weren't available. The best they could have done is give her a lot of intravenous fluids. . . . They had no way to cover exposed bone, no way to save skin."

The cast covering her torso - the first of many she would be put in over the years - caused pressure sores. "It is more difficult to cure the sores than the sickness," Kahlo wrote in one letter.

Lying in bed, immobile, also would have put her at risk of pneumonia and dangerous blood clots, said Steven Raikin, a Thomas Jefferson University Hospital orthopedic surgeon who specializes in foot and ankle trauma.

Indeed, her death certificate listed the cause of death in 1954 as "pulmonary embolism" - a clot in the lungs - and her husband, Rivera, said she was critically ill with pneumonia the night before she died.

By the end, Kahlo, addicted to painkillers, was barely able to sit in a wheelchair, even with a back-bracing corset. In all, she underwent 32 surgeries, according to Olga Campos, a psychiatrist and lifelong friend.

Several of Kahlo's lumbar vertebrae were fused together, and she had spinal bone grafts - operations still used today. But surgeons had none of the high-tech rods, screws and plates now used to strengthen or replace damaged bones. And despite the advent of antibiotics in the 1940s, the invasive procedures led to chronic bone infections and abscesses that required yet more operations.

Kahlo's withered right leg and foot surely contributed to her back problems.

"The trauma to her leg would have made her walk abnormally, predisposing her to spinal cord degeneration," said Raikin, the Jefferson surgeon.

That trauma also damaged blood vessels in her right leg and foot, starving the tissues of blood. She developed a chronic pressure sore on the foot, which ultimately became gangrenous and had to be amputated the year before she died.

Some biographers, including Herrera, have speculated that Kahlo became her own worst enemy, undergoing unnecessary surgeries in a desperate effort to relieve pain, or win admiration, or get attention from Rivera - or all the above.

"Every time Rivera found a new lover, Frida found a new doctor," said Salomon Grimberg, a Dallas psychiatrist, art critic, and author of several books on Kahlo. "Her injuries were very severe, but her psychological dynamics were more severe."

Still, medical science couldn't help but fail Kahlo. After Corzine was released from the hospital, he spent four months undergoing intensive physical rehabilitation. Kahlo went home to lie in bed for months, a prescription for atrophy and frailty.

Shortly before her foot was amputated, Kahlo drew herself as a one-legged doll losing its hand and head.

"I am DISINTEGRATION," she wrote above the sketch.

For a review of the art exhibit, and more about Frida Kahlo, go to http://go.philly.com/healthEndText