Virtual-reality war treats soldiers' stress

Patients' experiences come to light with the aid of software that simulates Iraq.

WASHINGTON - To a soldier who has been in Iraq, the sights, sounds and smells are familiar: the pop of an AK-47, the flash of a bomb, the stench of cordite.

The location is not.

In a small, windowless room at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, researchers are using the latest video-game technology - plus a smell machine and a vibration platform - to help patients suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder.

Known as "Virtual Iraq," the treatment could help many soldiers who don't find relief from medication or traditional psychotherapy.

"It really jogs their memory," says Col. Michael Roy, who runs the digital therapy program at Walter Reed. "It puts them back there very powerfully and makes them realize a lot of things they had consciously or subconsciously repressed."

Proponents of the treatment say once these memories are available, patients can begin to talk with therapists, eventually rendering the phantoms less terrifying.

Only about 50 soldiers nationwide have undergone the treatment in the last three years, leading some critics to say it is still unproven.

"We don't have empirical evidence that virtual treatment is needed. And it's quite expensive," says University of Pennsylvania psychologist Edna Foa, an exposure therapy expert. "I want to see what motivates this, other than a fascination with gadgets."

The number of potential patients is huge. PTSD - a debilitating ailment that leaves patients panicky, angry, and haunted by battle memories - is a significant problem for many of the 1.7 million soldiers who have served in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Virtual Iraq immerses patients in the harsh world that produced their symptoms.

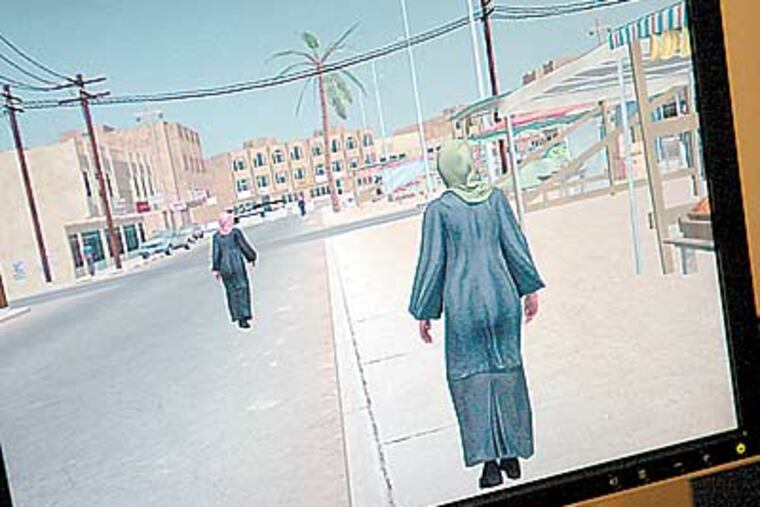

After putting on virtual-reality goggles and earphones, patients are transported to two scenarios: a humvee convoy through the desert or a foot patrol through a desolate city.

They use a video-game handset to control their movements. By turning their heads they can change what they see within that environment.

The therapist, who controls all variables in the environment except a patient's movement, slowly ratchets up the stress level by adding sirens, sniper fire and explosions.

This digital world is not only full of threats and stressors - roadside bombs, insurgent-fired grenades, a bleeding U.S. soldier slumped in the humvee's passenger seat - but also the mundane details that evoke everyday life for a soldier in Iraq.

Patients hear the sound of a Muslim prayer call and see Iraqi women walking to market in traditional clothes.

The setup also engages other senses. Under the patient's chair are powerful bass speakers embedded in a platform; when a bomb explodes onscreen, the concussion is palpable. Next to the computer console is a toaster-size odor machine; by inserting pellets, Roy can create a variety of smells, including sweat, burning trash, and Middle Eastern spices.

He suspects the scents and noise might be the most effective elements in evoking Iraq. The brain areas that process odor and sound are networked closely with the regions that play a key role in fear and memory - two key components of post-traumatic stress.

Many people with PTSD have trouble facing their terrifying memories. A significant percentage - Roy estimates as many as half of all patients - either refuse to enter into traditional therapy or don't finish it. It is this group that will most benefit from virtual therapy, proponents say.

The military doesn't allow mental-health patients to talk with the news media. But others who have seen combat say Virtual Iraq elicits powerful emotional responses.

Navy psychologist Scott L. Johnston spent nine months in Iraq in 2006 and 2007, most of that time embedded with Marine infantry units in Ramadi and Fallujah.

Although Johnston didn't develop full-blown PTSD, he did experience some symptoms after returning to the United States: He was hyperaware while driving, easily frustrated, and had trouble focusing.

When he put on the virtual-reality goggles, the environment triggered a visceral sense of being in combat.

"It brought me back to what I'd experienced," he says.