Glues promise to cut the need for stitches

Over the years, chemists have figured out how to make glues that stick to practically every material known to humans.

Over the years, chemists have figured out how to make glues that stick to practically every material known to humans.

Nowadays, that includes every material known to make up humans.

One of the latest adhesives for use in the body, TissuGlu, aims to eliminate the need for fluid drains after reconstructive surgeries such as tummy tucks or mastectomies. The Pittsburgh developers already have gotten it approved in Europe.

Another novel stickum may vastly improve surgeons' ability to repair congenital holes in newborns' hearts. The developer, Gecko Biomedical, has successfully tested the glue in animals.

"Now we have an adhesive that can be placed in the most challenging environment in the body - the beating heart," said company cofounder Jeffrey Karp, a biomedical engineer at Brigham & Women's Hospital in Boston.

Gluing or caulking skin, blood vessels, eyes, bones, and other organs may sound like science fiction, but it has become as standard as stitches and staples. Analysts valued the global market for tissue adhesives and sealants at $3.1 billion in 2012.

That's sure to grow, experts say, driven by pressures to speed up patients' recoveries and make surgeries less invasive.

The field of medical adhesives is young. The first one approved in the United States under modern device regulation was Dermabond, in 1998. (Many more have been approved in Europe, where the regulatory bar is lower.)

University of Pennsylvania emergency medicine physician Judd Hollander helped lead the clinical studies that proved Dermabond - made of cyanoacrylate, just like Krazy Glue - can safely handle uncomplicated cuts.

"If a kid has a simple laceration where the edges of the skin come together," Hollander said, "it's mean to use sutures."

Sutures - thread or wire sewn into the flesh - are a venerable way to manage cuts and incisions. They can withstand stretching and twisting, so the healing tissue rarely pulls apart. Absorbable threads don't even require removal.

However, sutures involve anesthesia, needle punctures, and a high risk of infection. Applying them, especially in inaccessible areas of the body, takes skill, and they may not be adequate in blood vessels or organs that leak blood or air.

Sticky stuff can overcome these drawbacks. The Food and Drug Administration has approved about 10 product classes.

Cyanoacrylate, which gradually sloughs off the healing skin, now is used on a quarter of all lacerations in emergency departments, said John Quinn, a Stanford University emergency-medicine physician and adhesive-industry consultant.

The compound generally can't be used inside the body because it sets off inflammation. But it's so safe on the skin that it is sold as over-the-counter "liquid bandages."

Another important type of adhesive acts as a sealant, preventing or stopping bleeding and leaks. The products have biological components - fibrin, thrombin, or collagen - and work by mimicking stages of blood clotting.

TissuGlu is a nontoxic version of urethane, the same versatile polymer used to make solvents, plastics, and more.

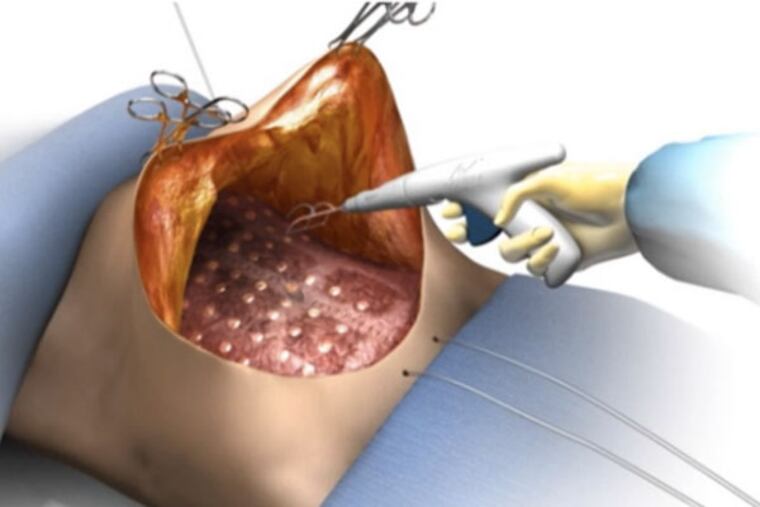

Applied as a liquid with a special glue gun, TissuGlu "cures" when exposed to moisture in the body, forming a stretchy seal that eventually biodegrades.

University of Pittsburgh polymer chemist Eric Beckman said he "stumbled" onto the innovative compound about 10 years ago. But it was Patrick Daly, chief executive of Cohera Medical, the company they formed, who found a niche for it: surgeries in which large sheets of skin and tissue are cut and reconnected. The trauma causes a buildup of fluid that must be siphoned off for days with plastic drains. (Actress/double mastectomy patient Angelina Jolie said it felt "like a scene out of a science-fiction film.")

Later, some women continue to be plagued by a stubborn pocket of fluid, or seroma, that has to be suctioned - or treated with yet more surgery.

In clinical studies, bonding the healing tissue layers with TissuGlu eliminated or reduced fluid accumulation and, thus, the need for drains. The product was approved in Europe in 2011; Cohera hopes to get the FDA's imprimatur this year.

In Germany, Christian Eichler, a breast cancer surgeon at Holweide Hospital in Cologne, said the only big drawback was price - about $500 per mastectomy patient. He reserves TissuGlu for patients who are frail or at high risk of seroma.

Paris-based Gecko Biomedical, meanwhile, is among biotechs taking cues from the amazing adhesion abilities of animals such as geckos, algae, barnacles, starfish, spiders, and mussels.

In a recent study of pigs, Karp and his colleagues used a nontoxic, ultraviolet-light-activated glue - made from natural glycerol and sebacic acid - to affix biodegradable patches on holes in beating hearts. The minimally invasive procedure holds promise for repairing heart vessels and heart defects in newborns.

"We've taken a bio-inspired approach because I think solutions are all around us," Karp said, "and evolution is the best teacher."

215-854-2720 @repopter