Treatment of last resort for C. difficile infection

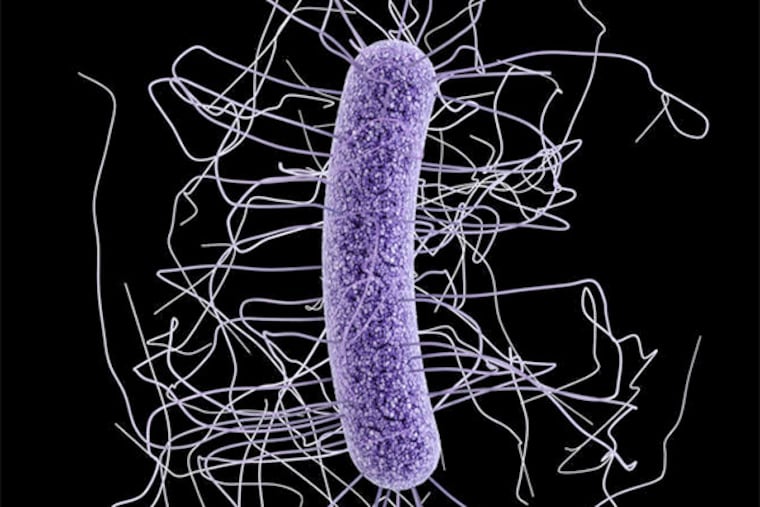

Just so you know, this story is not for the squeamish. It's about the therapeutic power of poop, a concept that is, we admit, both repulsive and fascinating. Specifically, it's about using one person's "donation" to cure another's Clostridium difficile, a potentially fatal bacterial infection that is growing more common and virulent.

Just so you know, this story is not for the squeamish.

It's about the therapeutic power of poop, a concept that is, we admit, both repulsive and fascinating.

Specifically, it's about using one person's "donation" to cure another's Clostridium difficile, a potentially fatal bacterial infection that is growing more common and virulent. The beneficial bacteria from a healthy person's gut can subdue the bad germs growing like crazy in a sick one's digestive system, even if many rounds of expensive antibiotics have failed.

Doctors say this form of transplantation, called a fecal microbiota transplant, or FMT, is exploding, thanks to impressive study results and more relaxed FDA oversight last year.

In 2012, Catherine Duff, founder of the Fecal Transplant Foundation, could find only one doctor in the country who was doing the procedure. She was so sick with C. diff, as the infection is called, that she did the DIY version, using enemas and her husband's fecal material.

"I'd been deathly ill for three months," said Duff, who lives near Indianapolis. "By 10 o'clock that night, I felt fine. If I hadn't experienced it myself, I wouldn't have believed it."

Now, she says, more than 50 doctors do FMT. She gets calls every day from more who want their names added to her list. Still, there are many states where no one does it.

In this area, doctors with Virtua Health do FMT. Bryn Mawr Hospital, the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, and Main Line Endoscopy Centers in Malvern recently came on board. Abington Memorial and Hahnemann University Hospitals are interested but haven't started yet.

Pablo Tebas, an infectious-diseases doctor at Penn, said it took a year to get hospital leaders to approve the new program. "When you explain it, people understand it, but the first thing is, 'You want to do what?' "

C. difficile infection, which sickens half a million people each year and kills more than 14,000, is both caused by and treated with antibiotics. Symptoms often appear after people have been hospitalized and received antibiotics.

The drugs save people's lives, but they also kill off beneficial bugs that usually would keep C. difficile in check. Think about what happens to a population of deer when they have no predators, Tebas said. A fecal transplant restores C. difficile predators.

Donors, who may be family members, friends, or strangers recruited by doctors, are screened for a host of infectious diseases. Most doctors use colonoscopy to deliver the donation, which is usually filtered and thinned with saline solution, but transplants can also be done by sigmoidoscopy, enema, or a tube threaded from the nose to the small intestine.

Penn chose the latter approach because it can be done by infectious-diseases doctors and because it was the method used in a pivotal New England Journal of Medicine study. The FDA requires patients to sign informed-consent forms.

On a recent day, a Penn patient in his 40s sat calmly while 250 ml of chilled liquid the color of French roast coffee with skim milk flowed through the nasal tube.

"It'll feel like you're drinking an Icee or something," infectious-diseases specialist Brendan Kelly warned him. The patient, who did not want his name used because of his job, gagged at the first jolt of cold, but eventually relaxed. After six months of C. diff, he said, he had "pretty much exhausted all of the other options."

The procedure was finished in minutes. "It wasn't as gross as we thought," his wife said.

Less than a week later, he said he'd had some cramping and was doing better than he normally would without antibiotics. He wasn't ready to pronounce himself cured.

Colleen Kelly, a gastroenterologist with the Women's Health Collaborative in Providence, R.I., began doing FMT in 2008 after a patient begged for it. She has since done 140 and is now involved in a blinded trial of the technique. She said patients with near-constant diarrhea for months easily lose their qualms. "They are desperate."

Tanya Boyd, a hospital employee from Clayton, Gloucester County, Penn's first FMT patient, has dealt with C. diff since 2011 and had tried fecal transplants before, with donations from family. They would work, but she would get reinfected. In February, her donor was an anonymous Penn employee.

"This time around," she exulted, "I feel reborn."

She thought it was "ludicrous" the first time somebody suggested a transplant, but she's totally sold now. She told her doctors, "I'm so sick, I'll put it in a bowl and I'll eat it."

Historians say the fourth-century Chinese used something they charmingly called yellow soup. Americans rediscovered the idea in the late 1950s, but it has been slow to take off in a nation obsessed with killing bacteria.

Ultimately, experts foresee a time when scientists will make the whole thing more palatable. They'll be able to lab-grow just the bugs that control C. difficile.

For now, though, the potential of poop is creating some bizarre situations. Patients are still desperate enough to try home transplants, sometimes without adequate screening of their donors.

Experts say some doctors have engaged in price-gouging, charging $10,000 and up for a procedure that should cost much less. (Insurance coverage is still variable, but many plans will cover parts of the process.)

"I've received e-mails from quite a few people who have used their pets as donors," said Duff, who can't imagine that is a good idea. "It's like the Wild West out there."

The FDA is trying to figure out how to regulate stool banks - personal donors can be hard to find - and is taking what some think is too hard a line. One stool bank, OpenBiome, pays Harvard and MIT students $40 for donations and then distributes the screened and prepared material to hospitals for $250.

Rebiotix, a Minnesota firm, is doing clinical trials of its transplant material, treating the enema-ready preparation as a drug. Others are testing a pill form that can be swallowed.

The FDA now allows doctors to give fecal transplants outside of research only to people who have failed all available treatments for C. difficile. Though some are eager to try it for other diseases, that is considered experimental.

There are now clinical trials testing FMT in patients with severe inflammatory bowel disease, ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome.

Colleen Kelly thinks it's not acceptable to do FMT for those other conditions outside of a trial. She gets 10 e-mails a week from people who want her to do just that.

Doctors said the procedure had thus far been most successful for C. diff.

The study published last year in the New England Journal found that 15 of 16 patients in the Netherlands - 94 percent - were cured of recurrent C. diff after one or two FMT treatments.

Meanwhile, vancomycin, the most widely used antibiotic, got rid of symptoms for only 31 percent. Some members of the FMT group had mild cramps and diarrhea on the day of the infusion.

Tebas said seeing that report "felt a little bit like a penicillin moment," a reference to another revolutionary treatment. He estimated that 100 to 150 Penn patients a year might qualify for the treatment, plus several hundred others in the region.

Though medicine has focused for years on bacteria that cause disease, the diverse community of germs that live inside us is suddenly a hot research frontier.

Gary Wu, a Penn gastroenterologist who heads the American Gastroenterological Association scientific advisory board on the gut microbiome, said there were a thousand different types of bacteria in our digestive systems, along with a thousand types of viruses. To that, you can add fungi and yeast and archaea, a life form that produces methane.

FMT, he said, is important because "it's the first evidence that you can change the gut microbiota very meaningfully to treat a disease."

But he added, he's in no hurry to use FMT to treat C. diff earlier in its course, or rush its use in other diseases.

"Just because you can do it doesn't mean you should be doing it in everybody," he said.

"This is not a completely innocuous thing. You're inoculating people with some of the most complicated biological communities on earth. We don't know most of what's actually in stool."

Neil Fishman, an infectious-diseases doctor and associate chief medical officer for the Penn health system, thinks FMT deserves a higher profile. As a country, we tend to think of medical innovation as a new drug or cancer treatment, he said.

"That ignores the fact that sometimes innovation is simple and elegant and gets to the core of the problem," he said. C. diff is a disease that is caused when we disrupt the normal bowel flora, and this treatment gives back normal bowel flora."

215-854-4944

@StaceyABurling