Philly scientists find prehistoric armored fish 'like a tank'

Its face, if you could call it that, looks like the visor on a medieval knight's helmet.

Good thing, because this creature was often under attack.

A team of Philadelphia scientists has discovered fossils of a weird, 370-million-year-old fish whose head and trunk were encased in armorlike bony plates, with a small slit for its eyes to peek through.

At 5.5 feet long, the creature was the largest known fish of its kind. So the scientists dubbed it Bothriolepis rex — B. rex for short, a nod to the much larger dinosaur T. rex.

"It's like this tank," said Jason P. Downs, an assistant professor of biology at Delaware Valley University in Doylestown.

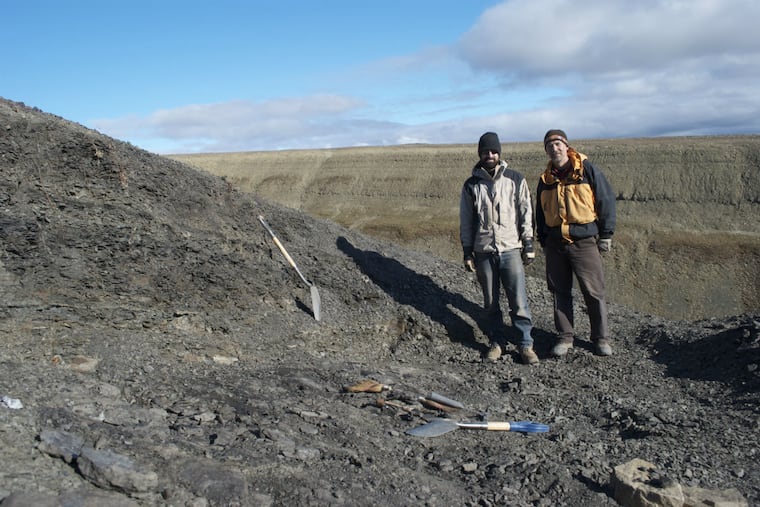

The fossils were excavated during multiple excursions to remote Ellesmere Island in Canada, north of the Arctic Circle, between 2000 and 2008 — a land mass that was located near the equator when the fish was alive.

The crew came back with so many fossils from different species that it has taken years to analyze all of them, said team member Edward B. Daeschler, a prominent paleontologist at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University.

"There is lots more in our cabinets," said Daeschler, who also digs up ancient fish in Pennsylvania.

The team published a detailed description of the new species online in October in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. In addition to Daeschler and Downs, the authors included University of Chicago professor Neil H. Shubin and Valentina E. Garcia, a former Swarthmore College student who is now a graduate student at the University of California, San Francisco.

A key reason paleontologists are drawn to the study of prehistoric fish is because of what the animals can tell us about evolution. Humans descended from some of these early fish; Shubin wrote a 2009 book titled Your Inner Fish: A Journey Into the 3.5-Billion-Year History of the Human Body.

The book was partly about the most famous ancient fish of all, Tiktaalik roseae, the discovery of which Daeschler and Shubin announced in 2006. That fish had unusual muscled fins that likely enabled it to creep onto land for short stretches.

The newest old fish, B. rex, is from a different branch of the evolutionary tree, and has no close relatives alive today.

It was likely a slow-moving bottom feeder, "sucking up invertebrates and decaying plant material," Daeschler said.

John A. Long, a paleontologist at Flinders University in Australia, agreed.

"It could have been a mud-grubbing feeder on detritus," said Long, a past president of the Society of Verterbrate Paleontology. "Or feeding on small crustaceans by filtering the water is another suggestion."

The armor covering its head and trunk — more than an inch thick in spots — was useful in warding off attacks from sharp-toothed predators. Its genus name, bothriolepis, comes from Greek, referring to the pitted nature of the armor-like bone. Its tail, however, was unarmored.

"You can kind of think of it as swimming with the top half of a suit of armor on," said Downs, who is also a research associate at the Academy of Natural Sciences.

Smaller cousins of B. rex have been found on other continents, and apparently the scientists who found them were similarly impressed by their size. One was dubbed B. gigantea. Another was called B. maxima.

But the new find is the biggest yet, thus the rex, meaning "king."

"It's a little bit of one-upmanship in the naming," Downs said.

Large body size can help in defense against certain predators. In this case, the attackers included other prehistoric fish with sharp teeth.

But large size also comes at a cost. Big animals have to eat a lot.

Did the reign of B. rex come to an end because of a shortage of food? No one knows.

But Daeschler and Shubin are headed off to another remote location in December in search of more clues to this time in prehistory, called the Devonian period, with support from the National Science Foundation.

This time the destination is Antarctica, which, like the Canadian island that yielded B. rex, was located near the equator during the Devonian period.

It is a reconnaissance mission to scout out locations for future excavation — and, perhaps, more fossils for the academy's cabinets.