Philadelphia officials argue over updated LED streetlights

In Pittsburgh, city workers have just completed a test of about 50 different LED streetlights from 30 companies, aiming to replace all of the city's 40,000 streetlights in what would be one of the largest public works projects in the Steel City's history.

In Pittsburgh, city workers have just completed a test of about 50 different LED streetlights from 30 companies, aiming to replace all of the city's 40,000 streetlights in what would be one of the largest public works projects in the Steel City's history.

Los Angeles started swapping out 140,000 of its streetlights with LEDs - light-emitting diodes - several weeks ago. And Seattle will start replacing half of its 84,000 streetlights next month.

Philadelphia, suffice it to say, is not in the vanguard of what promises to be the next great leap ahead in municipal-lighting technology.

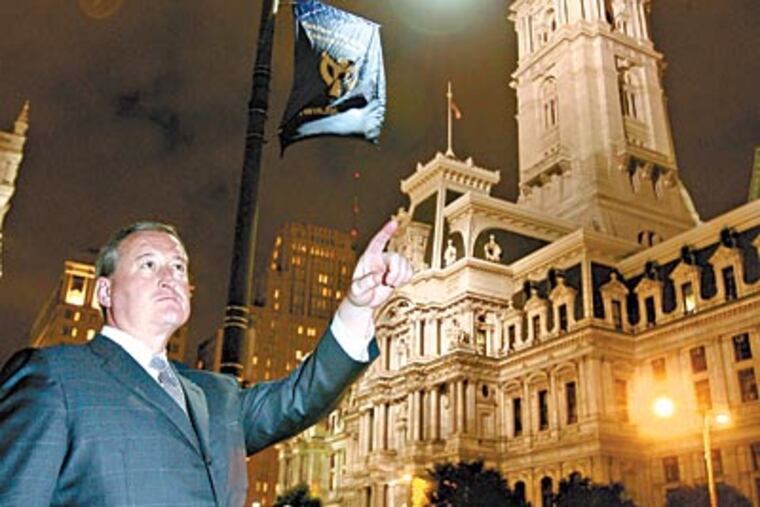

But even here, atop two light poles outside the north portico of City Hall, four LEDs made by General Electric Co. emit light that is whiter, brighter, and, in the long run, cheaper than the electric incandescent lamps they are replacing.

Inside, City Councilman James Kenney sparred with Streets Commissioner Clarena Tolson last week at a hearing on the promise, and problems, associated with a mass conversion to LED. That still appears to be some time off in Philadelphia, thanks to problems with up-front costs, still-emerging technology, and the city's street-lighting contract with Peco.

"The problem with Philadelphia is we're never out in front," Kenney said. "I would like to be at the forefront of something."

Since the city has replaced traffic signals with LED versions, Kenney would like to see workers at least phase in LED streetlights, perhaps starting with high-crime districts. Money saved on electricity and maintenance could pay for the next round.

It would turn that yellow of the current high pressure sodium lights to a much whiter shade.

It would also be a smarter light. Systems can be programmed so that lights could blink to guide emergency crews to a location, or dim when a park closes for the night.

The LEDs would come with a hefty up-front cost, upward of $50 million to replace the city's 108,000 streetlights.

At the hearing, Kenney asked two firms - Anaconda Enterprises L.L.C. and IntenCity Lighting Inc. - if they would be willing to build an assembly plant in the city and hire former prisoners.

Both said it was possible.

'Not there yet'

But Kenney got some push-back from Tolson and her chief traffic and street lighting engineer, Joseph M. Doyle, both of whom said the technology wasn't ripe.

"At some point, it's going to be ready for the curbside," Tolson said, "but it's just not there yet."

Doyle said that "under various swap-out scenarios," the annualized costs would be several million dollars more than the city currently pays.

Part of the reason is the city's current contract with Peco Energy. Two-thirds of the city's $13 million annual electricity cost for its streetlights is a fixed connection fee; only one-third is the cost of energy, which will increase when rate caps come off Jan. 1.

But Kenney said he felt certain that, given Peco's energy-efficiency mantra, the utility would accept changes.

A Peco spokeswoman agreed that the utility would work with the city and noted that Peco already offers rebates for municipal customers to help offset the shift to LEDs.

LEDs are already popping up across the region because of energy savings that reach 60 percent. Coupled with lower maintenance costs - lights need to be changed just once a decade or more - the savings would pay for the new lights over time.

Then there are safety and security benefits. A person who in a security camera image appears to be in a yellow jacket would actually be wearing one, not a white jacket that just looks yellowish.

In Delaware, a Delmarva Power test project is under way in Wilmington, along Broom Street. Several towns in the Pennsylvania suburbs have applied for grants to fund LED streetlights, but were denied. Quakertown plans to go ahead anyway in 2011, replacing bulbs as they burn out.

Ursinus College put some along Collegeville's Main Street where students cross.

Nationwide, interest in the technology has been so high that the Department of Energy in April announced a national collaboration on LED streetlights, led by Seattle City Light, the city's publicly-owned utility.

Seattle's manager of streetlight engineering, Edward Smalley, said the plan was to share information from municipalities that have already pulled the trigger and to develop specifications to streamline the bidding process.

While many companies use the same LED technology, it's not "a bulb in a box," as one industry official said. The engineering of each company's "luminaire" differs.

Smalley thinks the biggest savings are not in energy, but in maintenance.

The current high pressure sodium lamps have to be changed every four years. With LEDs, "you're talking up to 12 years," he said.

How many city workers does it take to change a bulb?

"For you and me, a few minutes," Smalley said. "But for a city, it requires a heavy truck and at least two people - $120 minimum." Repeat that for thousands of bulbs over the course of a year, "and there are significant dollars there."

Smalley ranks the light quality as the second-best benefit, although some in Los Angeles are already complaining that the new lights are overkill. "I thought Jesus was coming to my house on Saturday night," one resident complained on a community website.

One characteristic that has made LED lighting so problematic for, say, end-table lamps - it's directional - works well for streetlights.

Most LED bulbs shine down on the street, instead of out into windows or up into the sky, both of which waste electricity and prompt complaints of light pollution.

LED technology also has the potential to bring "smart" moves to city lights.

A year ago, San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsome turned on a test bank of LED streetlights with his iPhone and then made them blink, showcasing the ability to use streetlights to guide emergency crews to a particular spot.

Municipal lighting technology has changed roughly every quarter-century. First, there were candles, then gas-powered lighting, then electric incandescent lamps, and so on.

Smalley says we're at another juncture now. "We're going to see over the next five years, many owners of public lighting across the nation make another conversion to a newer, more efficient technology yet again. That would be LED."

Sealing the deal

University of Pittsburgh researchers recently completed the first cradle-to-grave analysis of street lighting, at the city's request.

They looked at four technologies, including another newbie, induction lights. They concluded that LEDs were best, considering brightness, affordability, and conservation over their life span.

That sealed the deal for Pittsburgh City Councilman William Peduto, who said that officials were analyzing public feedback - they created a website to gather comments on the city's test projects - and pulling together other findings.

He wants to use the project to rethink city lighting. He wants to map the lights and look at why some streets have more than others. "We're trying to create an equity for urban lighting," he said.

Still, he knows that the technology is advancing so rapidly that "the person who comes out of the gate first is going to have a system that is antiquated before it is even completed."

Kenney, for his part, intends to keep pushing.

"I'm not asking them to jump off a cliff and make a commitment to every light," he said of the streets department. "But I would like them to start thinking more energetically about the possibilities."