Five years after breast cancer, a survivor feels cut off from the care that kept her safe

The physician's assistant keeps saying how great it is to celebrate five years cancer-free with me. I don't feel nearly as excited about this as she does.

In the waiting room of the breast surgeons' office, I overhear a conversation between the receptionist and a woman wearing a pink hoodie, pink T-shirt, pink sneakers, and purposefully tattered jeans. She is saying she's so tired, she's been at the hospital since 5 a.m., getting scans, blood tests, she doesn't know whom to entrust with the X-rays she's been carrying around.

"These are my responsibility now," the receptionist says as she takes the X-rays. She hands the woman a ticket good for free parking and a meal. I can feel a buzz beginning in my chest, the familiar hum of my anxiety spreading from my heart to my lungs, up to my shoulders, down my arms and to my fingers, which shake slightly.

Five years ago, I was that woman, having the same conversation before my day of pre-surgical check-ups.

Now I am waiting for my annual post-mastectomy breast exam. I try to greet the nurse who calls my name with a smile despite the pit in my stomach growing larger as my memories settle in.

"Congratulations!" she says. "Five years now. This will probably be your last visit."

The buzzing continues, but my mind snaps back to the present. "Thanks," I mumble.

Congratulations? For what? When she closes the door to the exam room so I can change out of my clothes, she says, "Good luck to you." She expects never to see me again.

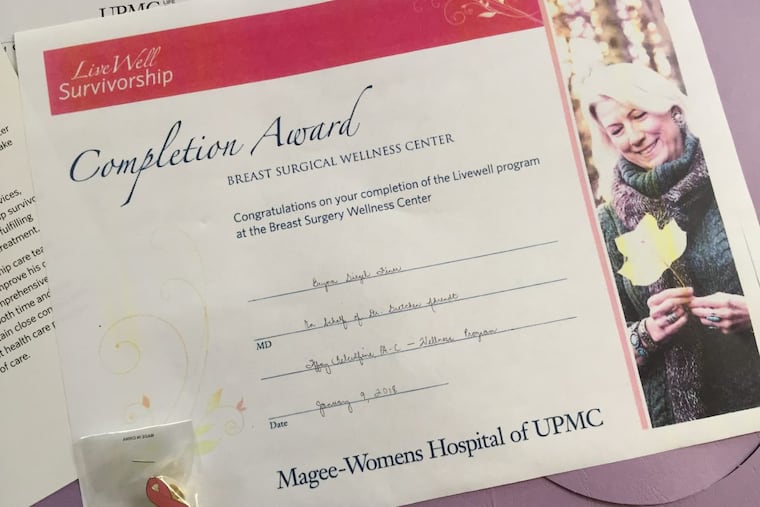

I had forgotten that five years out is supposed to be a milestone, cause for celebration; you're cancer-free. The physician's assistant who examines me even gives me a certificate (pink, of course) for completing a wellness program I didn't know I was participating in. Apparently having my yearly exam is an award-winning achievement.

The physician's assistant keeps saying how great it is to celebrate five years cancer-free with me. I don't feel nearly as excited about this as she does.

I realize I don't want to be free.

I have reduced my cancer risk as much as a BRCA-positive woman can – having a double-mastectomy, removing my ovaries, then having a total hysterectomy to eliminate any space for cancer. But I know there is only risk reduction, never risk elimination.

I feel like I have been unwillingly cut loose from the surveillance keeping me safe the last five years. Now I'm falling.

In 2012, when medical authorities published recommendations that women begin to have pap smears to screen for cervical cancer every three years rather than every year, many women became terrified. A New York Times article describing the new recommendations has more than a hundred comments by women who are angry and scared that they might develop cancer between those three-year intervals. Many women expressed similar outrage when recommendations for a first mammogram were changed from age 40 to 50. While there is much evidence of the risks of overdoing screening tests, it is understandable that women feel a sense of security being taken away, like a rug being yanked out from under them.

My body continues to buzz as the physician's assistant palpates my breasts, now made of abdominal tissue surgically sewn into place. They are completely numb to her touch. She washes her hands after completing the exam and says cheerily, "You don't need to come back if you don't want to."

I feel a sudden glimmer of hope. "But if I want to, then I can continue to come back each year?" I ask.

She tells me of course I can, that there's really no need, but one never knows. "We just don't know a lot about these things," she says. These things. I am assuming she means post-care for BRCA-positive patients because there is no standard of aftercare established for women such as me, those who have had a cancer or pre-cancer diagnosis and are high-risk because of a genetic mutation. Look at conversations in any BRCA Facebook group and you'll see women asking each other about their doctors' recommendations, confused about all of the conflicting advice we receive.

The physician's assistant shakes my hand, gives me the certificate and a pink ribbon pin in a purple folder, and says goodbye, as if for the last time.

Studies are inconclusive about the chances of breast cancer recurrence in BRCA-positive women and are often difficult to interpret. As a woman diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ at age 36, my situation is even more complicated. Overall, these studies show that risk of recurrence after mastectomy is low, but they seem to indicate that the chances can possibly increase 20 years post-surgery, depending on the type of cancer first diagnosed. Fifteen years from now, my son will be 21 years old; I will be 56, and will have just celebrated with my husband our silver wedding anniversary. I expect to have a lot of life left.

As I drive away from the hospital, Radiohead's "Karma Police" comes up in my playlist. I'm hardly listening as I concentrate on keeping my buzzing hands steady on the steering wheel, watching the road through teary eyes. Suddenly, I find myself singing along with Thom Yorke, "For a minute there, I lost myself. I lost myself," as I clutch an appointment card for next January between my fingers.

Bryna Siegel Finer tested positive for the BRCA2 mutation and, after seven years of screenings, a mammogram discovered DCIS in her right breast. She teaches writing at Indiana University of Pennsylvania and lives in Pittsburgh with her husband, who is BRCA1 positive, and their son. She is a peer support group co-leader for FORCE Pittsburgh and can be reached at brynaf@facingourrisk.org.