Can neurofeedback help you think your way out of depression?

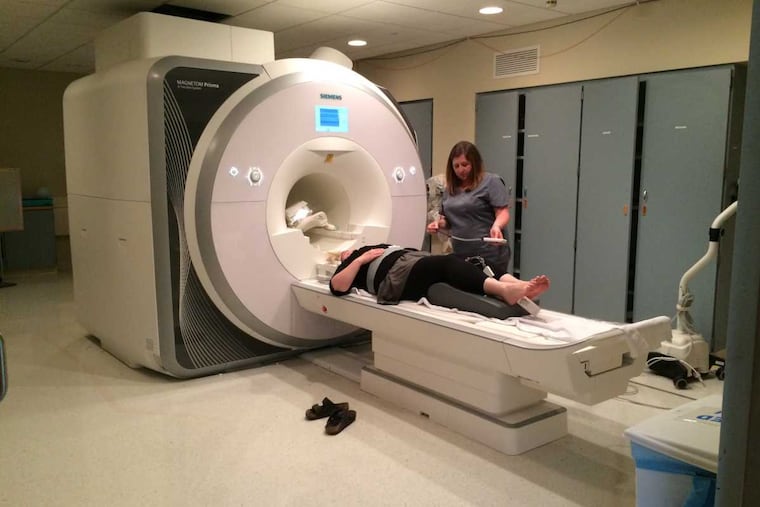

Study subjects at the University of Pittsburgh get immediate feedback through MRI scans about what's happening in their brains when they try to recall positive memories.

Denise Gross has been depressed for about five years, despite treatment with antidepressants and talk therapy.

So she was willing to take a leap when she heard that researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine were testing neurofeedback — a way to see and change what the brain is doing, in real time — for depression.

"I actually kind of enjoyed that, the idea that it is possible to change the way you think," said Gross, a 36-year-old English teacher and mother of two from Dravosburg, a borough near Pittsburgh. "I find that fascinating as an educator."

That's how she wound up earlier this month in a clinical trial of the novel treatment at UPMC Presbyterian. She would spend 90 minutes in a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine — that's a feat in itself — seeing whether she could learn to control activity in a particular part of her brain while thinking of positive memories.

"It's a potential, side-effect-free new treatment for depression," lead researcher Kymberly Young told Gross before she slid into the narrow tube of the MRI and awaited neurofeedback. Once the team had mapped her brain, she would see a thermometer-like graph that showed oxygen and blood use in the left amygdala, an almond-shaped structure within the temporal lobe best known for its role in responding to frightening events. It also is involved in emotional processing and, through connections to other parts of the brain, in memory and emotion regulation. Gross' challenge would be to move the graph upward while thinking about happy times.

Young, who came to Pitt a year ago from the Laureate Institute for Brain Research in Tulsa, Okla., had already shown in a smaller study that the approach had promise. In that study, published in April in AJP in Advance, an online publication of the American Journal of Psychiatry, 19 people who tried neurofeedback involving the amygdala were much more likely to feel better afterward than a 17-member control group that received feedback about the intraparietal sulcus, a part of the brain not involved in emotion regulation. Twelve participants in the amygdala arm of the study had a 50 percent improvement in their score on a depression rating scale. Only two in the control group met that goal. There was no follow-up after the first week, so there's no way of knowing how long the effects of the intervention lasted.

Caryn Lerman, vice dean of strategic initiatives at Penn Medicine, is studying how electrical and magnetic stimulation of the brain can affect behavior, particularly with cigarette addiction and ADHD. She, too, is moving into using feedback from functional MRI (fMRI), which measures activity in the brain, as a complement to the other approaches. Using it in real time has been challenging, she said, and is still in the "very early stages of development."

She said Young's work "represents a great advance in this space" and has potential applications in other areas of psychiatry and neurology. The challenge, she said, "will be to translate this into an intervention that can be used more widely."

That is a high priority for Young, who wants to develop a usable treatment within 10 to 15 years. "So much of mental-health research we've done has never left the world of science," she said.

She hopes to correlate fMRI results with electroencephalograms, which require sensors to be placed on the subject's head. These tests are cheaper and don't unnerve people who don't like tight spaces. Insurance companies aren't likely to pay for fMRIs — she pays $651 an hour to use the machine — for the legions of people with depression, but they might, she said, for those with intractable symptoms.

Young said other researchers are also testing neurofeedback for PTSD, smoking, spider phobia, tinnitus (ringing in the ears), Parkinson's disease symptoms, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The study Gross has joined will have 60 participants. They will get two sessions in the MRI followed by 10 sessions of cognitive-behavioral therapy, a proven form of talk therapy that helps patients change thinking patterns. Depression symptoms will be measured every week during the first five weeks and again at the end of treatment. The control arm again will get feedback from the intraparietal sulcus.

There is evidence that people with depression are not as good as emotionally healthier people at recalling autobiographical memories, Young said. This is particularly true for positive memories. The intervention is meant to help people recall good events and savor them. The trick is not to just think of the event. That actually makes people more depressed, she said. You need to think about why it made you happy, how it made you feel. (People with bipolar disorder are not allowed to try this form of neurofeedback, Young said. It can prompt manic episodes.)

Young, whose father was a Disney imagineer who designed the sound for rides in theme parks, used a Disney metaphor. Think of Peter Pan. He can think all the happy thoughts he wants, but, if that's all he does, he'll die if he jumps out the window. Only in the presence of pixie dust can Peter fly. "For me, the neurofeedback is the pixie dust," Young said.

Some study subjects, Young said, have trouble thinking of any positive memories. She's tried the experience herself and found that thinking of happy times with her cats worked best. To her husband's dismay, she said, "my wedding in Hawaii was not as effective as my cats." Many women, she said, think of pets and babies. Men are more likely to think of skydiving, sex, and paintball.

Gross' task, while trying to ignore how the MRI machine cramped her shoulder, was to think off and on about happy events, including visiting Walden Pond, participating in Highland games at the Dublin Irish Festival in Ohio, and taking a family trip to Disneyland. In between, she was instructed to count backward by various numbers to clear the cognitive palate. Young and other members of her team were watching from the control room. Her results were variable, but she was sometimes able to make the graph top out, and Young said she improved over the session.

Reached after her second time in the MRI, but before she had started talk therapy, Gross said she felt better after both sessions, even though she didn't think she did as well during the second one. She's been sick and still was feeling below par. She said she discovered she could move the bar by focusing on the feeling rather than the mental image of a memory. What worked the best was thinking about times when she had felt empowered, loved, or surrounded by family while enjoying something together.

Going to the Highland games was a high point for her. She'd done it to help someone out, without much preparation. She was not her usual perfectionist self and enjoyed the large crowd. It was exhilarating, she said.

Seeing how the neurofeedback made her feel has made her consider trying a gratitude journal again, something others have suggested. She's tried before, but thinks she'd do it differently now, focusing less on material things and more on feelings.

Even on the day when she thought she'd done poorly, she felt better when the experiment was done. When she got home, she told her husband what she'd thought about in the MRI. They reminisced about their wedding day. "It brought a lot of joy to our day," she said.